The 20th century comprised a long stride towards a more peaceful world. (Pixabay CC0 Public Domain)

The century of peace. The 20th century laid the foundations for what could make our century a century of peace.

The 20th century is often referred to as the bloodiest in human history. Towards the end of that century, the historians Eric Hobsbawm, Gabriel Kolko and Niall Ferguson published general narratives entitled, respectively, Age of Extremes, Century of War, and The War of the World.

Last year there were many publications warning against the outbreak of a new world war of the same kind as the one unleashed by the Guns of August one hundred years earlier.

Yet, in spite of all the turmoil in Ukraine and the Greater Middle East, and the squabbles in the South China Sea, we came nowhere near a world war.

In our view, despite the two world wars, the Holocaust, the gulags, the atomic bomb, Maoism, the Khmer Rouge, and Rwanda, the 20th century should not be reviled. It comprised a long stride towards a more peaceful world. Moreover, the century became more peaceful as it drew to a close, thus creating a real possibility of making our century into a century of peace.

Brutality

Anyone looking for examples of brutality in the previous century does not need to look far. The three worst catastrophes were the First and Second World Wars and China’s “Great Leap Forward” (1958–61). Together these events are estimated to have cost 100–115 million human lives. It is impossible to establish more precisely how many people died as a result of fighting, massacres, ill-treatment or war-related starvation and disease. Much knowledge is lacking, and there are also many different methods for calculating death tolls.

The criteria for awarding the title “most brutal century in human history” are unclear. It is misleading simply to count how many individuals were killed. The world’s population grew dramatically during the 20th century, so when comparing the numbers of violent deaths in different centuries, we should consider percentages of world population as well as total deaths.

The competitors

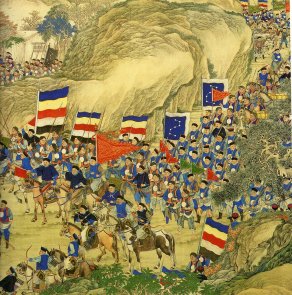

Detail from The suppression of the Taiping Rebellion, ink and colours on silk. Artist unknown.

Which century has been the most brutal? The 19th century was not as peaceful as many people suggest. The Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil War were bad enough, but they were far from the most devastating events. The century’s worst catastrophe was the Taiping Rebellion (1850–66) in China, estimated to have cost 20 million human lives, many as a result of appalling massacres. Meanwhile the country that lost the largest proportion of its population during the 19th century was Paraguay, where at least half the population perished between 1864 and 1870.

Soldiers Plundering a Farm during the Thirty Years’ War, 1620. Sebastian Vrancx (1573-1647); Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin.

A far stronger candidate, however, is the 17th century. The Thirty Years’ War in Europe (1618-48) was catastrophic. Around a million men fought on the various sides, but they took more lives in their hunt for food than on the battlefield. Around 8 million people are thought to have died, the majority from starvation and disease. In America during the same period the native population was being wiped out, for the most part by disease but also frequently by violence. In China, some 25 million people died in the war that ended the Ming Dynasty and brought the Manchus (the Qing Dynasty) to power. The world population at that time was approximately 600 million.

The Black Death

From Theodor Kittelsen’s collection”Pesta”, illustrating the Black Death.

The 13th and 14th centuries were also extremely violent. First came the Mongol invasions of Europe, India and China. These were followed by the Black Death, which may have claimed 100 million lives. And then came the devastation brought about by the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur (Tamerlane). These two centuries must count definitively as amongst the worst in human history. The Aztecs were also building their empire during this period. Although we lack reliable estimates, it is clear that their conduct was grotesquely brutal. At this time the world population was around 400 million.

What counts?

Is it right to include the Black Death in this context? If we include the victims of epidemics during other wars, then the answer must at least to some extent be yes. The numbers of lives lost in the First World War generally include the victims of the “Spanish flu” pandemic, and figures for the Second World War generally include the millions of victims of starvation and disease in Burma, Ukraine, Russia, China and Vietnam. The terrible consequences of the Black Death were in many places related to war and conflict.

Balancing the picture

Although it is difficult to reach a conclusion as to the proportion of Black Death victims whose deaths can be attributed to war and violence, this does bring us to an important point. If we are to obtain a balanced view of the horrors of a particular century, it is essential to consider the overall picture. In the 20th century, chemistry revolutionised public health, dramatically increasing the average life expectancy of a new-born child. And as Steven Pinker and Joshua Goldstein pointed out in their 2011 books The Better Angels of Our Nature and Winning the War on War, the 20th century was characterised by a reduction in the amount of brutality in people’s everyday lives. Not only did we get better medicines, we also got more – and more nutritious – food, workplaces became safer, and there was a huge drop in everyday violence.

Even though chemists also produced Zyklon-B, their medical innovations put the 20th century clearly on the positive side. The best indicators are statistics for the world population, which increased from 1.7 billion in 1900 to 6 billion in 2000.

Oppression

Eleanor Roosevelt with the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Although many people suffered serious oppression under dictatorships during the 20th century, it was probably the least oppressive in history. Although human rights have deep historical roots, it was not until the UN’s Universal Declaration of 1948 that human rights gained general support.

Freedom has grown in many different fields. Democracy became a more widespread political system. Market economies, with varying degrees of regulation, and well-functioning welfare states have provided billions of people with economic freedom and security.

The winner

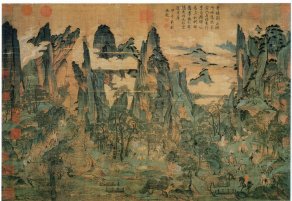

An Lushan Rebellion: Emperor Xuanzong of Tang fleeing to Sichuan province from Chang’an to escape the violence. Artist: Li Zhaodao, from the 11th century

So which was the most brutal century in world history? Our top candidate is the 8th. Both Christianity and Islam were spreading rapidly and the two religions clashed with enormous consequences for ordinary people. And although there were a few exceptional periods, there was more-or-less permanent war in the most populated parts of the world. We find the deciding factor in China. When General An Lushan rebelled against the Tang Dynasty in 755, he triggered eight years of war. Although the figures are highly debatable, the Middle Kingdom was already keeping track of its population at that time, and the post-rebellion census showed a fall in population of 30–40 million. Deaths were not the only factor: some of the population had fled, and the Tang Dynasty had suffered territorial losses. Even so, the war must have been an almost unparalleled catastrophe. At that time the total world population was only around 280 million.

The loser

We have now passed the 2014 milestone without any outbreak of world war. If the next 85 years are as peaceful as the first 15, the 21st century will “lose” our contest and be the least violent in human history. We know this runs against the impression created by the ongoing wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Syria, Yemen, and other places, which have boosted the number of global conflict related deaths since 2011. The year 2014 was the worst year since 1988, and although we do not yet have the figures, there is little to indicate that 2015 was better. Yet, in spite of this worrisome five-year trend we can say with considerable certainty that the 21st century, unless there is a much bigger catastrophe, will be the “oldest” in human history. Never before have so many people lived such long lives. For this we must thank the people of the 20th century who laid the groundwork for the option we still have to build a century of peace.