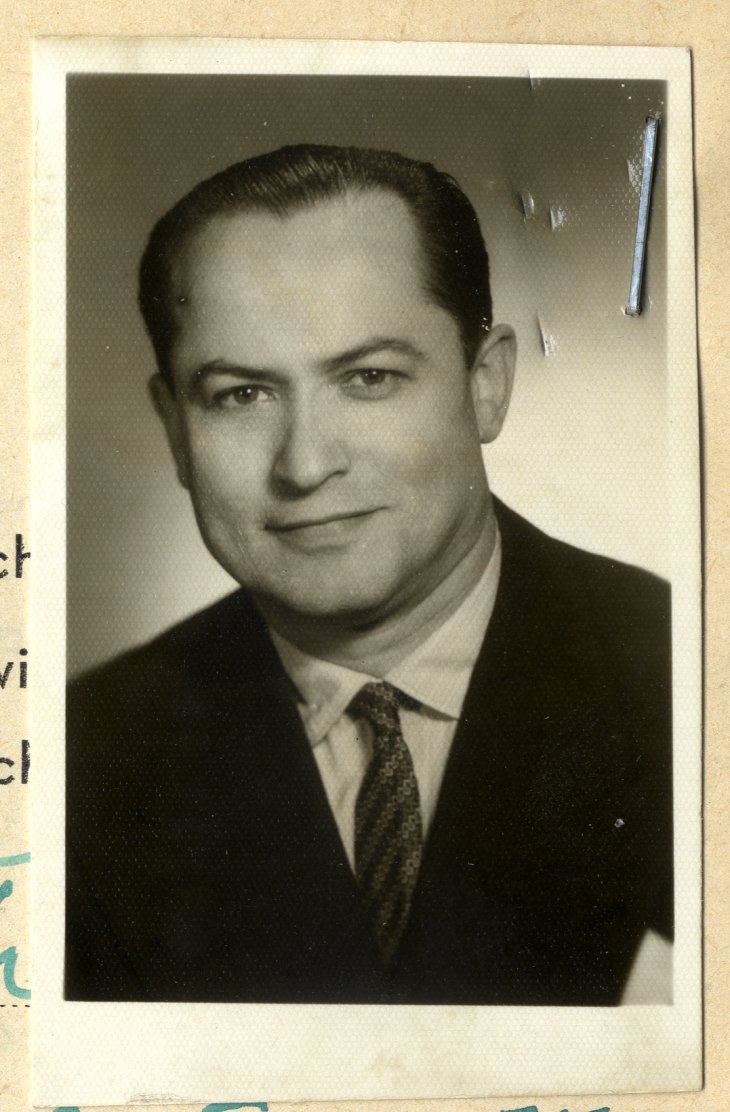

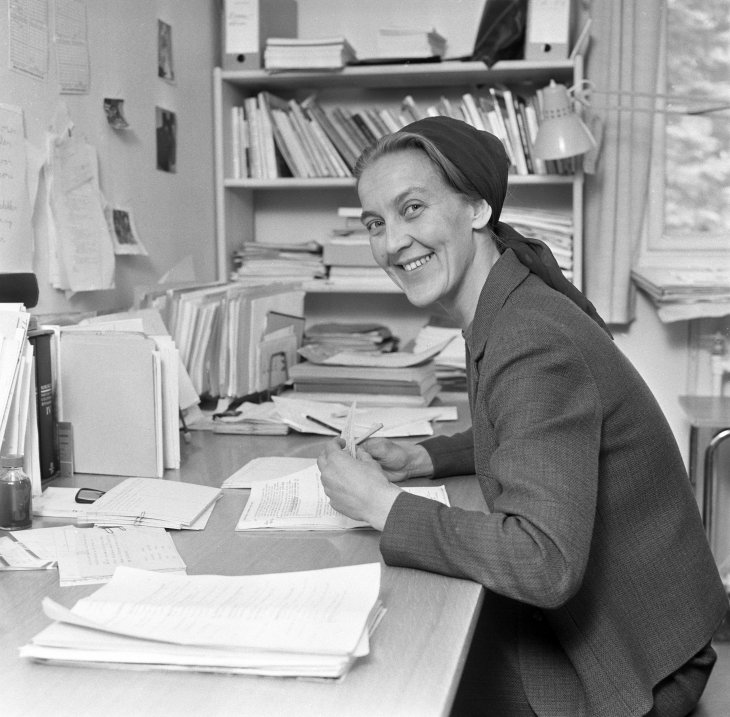

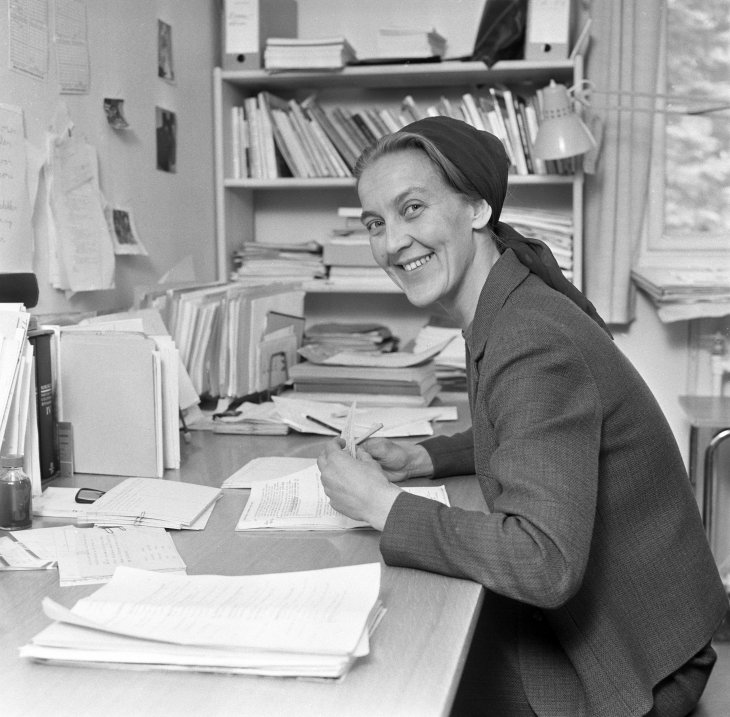

Ingrid Eide at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) in 1968. Photo: Henrik Laurvik / NTB / Scanpix

When people ask what peace is, I urge them to tell me what they associate with war. They answer death, destruction, battles, arms, hatred, uniforms, suffering, fear, anxiety, loss, misery, and much else, all of which are bad and sad. Then I suggest that peace could be the opposite: life, construction, debates, tools, friendship, a colourful dress, thriving, safety, serenity, gain, prosperity, all of which are good and enjoyable. The exact meaning of peace will differ from one person to the next, but it is always the opposite of war. This is how I saw it after the War, and this is how I see it today.

Ingrid Eide, interviewed by Stein Tønnesson

Ingrid Eide receives me at her home in Bjerkealléen (The Birch Alley) at Grefsen, Oslo, the neighbourhood where she grew up. She sits down in front of a painting of her mother, the teacher and peace activist Ragnhild Hjertine Haagensen Eide (1901–91), who also grew up at Grefsen. They resemble each other. I get a feeling of listening to both at the same time, speaking to me with a warm, firm, compelling voice.

Stein Tønnesson: When you say, ‘the War’, I suppose you mean the Second World War, when Germany occupied Norway. You grew up with that war. How did it form you as a sociologist and peace researcher?

Ingrid Eide: I had turned seven when the war came to Norway, and had started school at Grefsen. I was twelve before the war was over. Those five years gave me so many memories. I believe they were decisive for my later dedication to the mission of the United Nations and my enthusiasm for developing peace research.

Read More