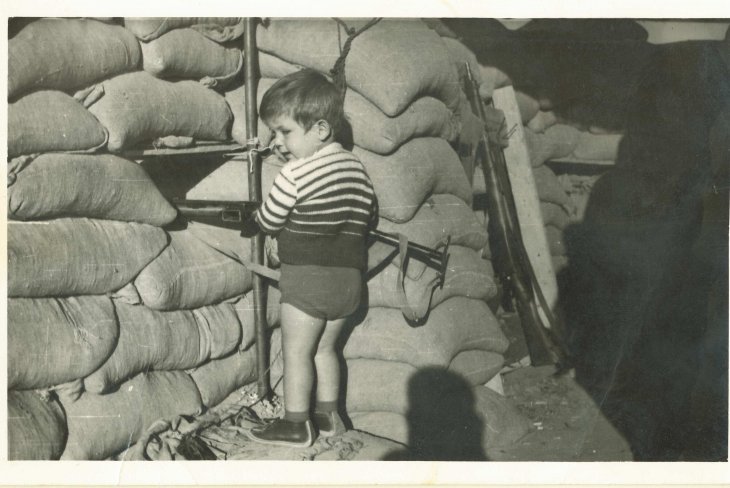

At the age of two, Mete Hatay plays in the barricades that surrounded the neighborhood in Cyprus where he grew up. Photo: Private archives

Mete Hatay, interviewed by Cindy Horst

Seeing victim become perpetrator, perpetrator become victim – seeing them change places depending on the situation – triggered a lot of questions in my mind…

Whatever you imagine for the future, you always construct it from the past. And you cannot say, ‘let’s put the past behind us and start now’, because the property title still comes from the past. You cannot say: ‘All right, I’m keeping the property, let’s put the past behind us’, you cannot do that. Rhetorically, of course, you have to start a new life, but in reality, you always have the past haunting you – physically as well as emotionally, both through legal means, and in how history is written.

In order to tackle these problems of the different pasts, and different visions, and different truths, we have aimed to prepare a third space for multiple perspectives. So that everybody can bring their perspectives and have a debate about it. So that we can strive to a certain compromised truth somehow. To help develop new strategies.

Mete Hatay has worked at the PRIO Cyprus Centre (PCC) since its inception in 2005. The PCC functions as an independent, bi-communal centre committed to both research and dialogue. Its aim is to contribute to an informed public debate on key issues relevant to an eventual settlement of the Cyprus problem. The researchers attached to the Centre are both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots as well as individuals of other nationalities.

Talking to Mete, I am again struck by the incredible value of experiential knowledge from contexts of war and oppression in peace research, as well as the ways in which traumatic experiences during violent conflict can inspire action towards social justice. Such experiential knowledge has inspired the founders of PRIO, who grew up during the Second World War, and it is also a real asset for the PCC.

Cindy Horst: Could you start by telling the story of your life, pretty much from the beginning?

Mete Hatay: I was born in 1962 in the Republic of Cyprus, before the division of the island. I grew up in the enclaves, the Turkish Cypriot ghettos, which were established because of intercommunal fighting that had begun three years after the founding of the republic. The ghettos were spread around the island, covering around three percent, I think. Turkish Cypriots were then 20 percent of the population.

It was a bit like Gaza, but many smaller versions of Gaza, in different places. I spent my childhood in these ghettos, until I was 12 years old. We couldn’t get out when I was small because of a siege for three and a half years between 1964 and 1968. No one could get out, and no one could get in, either. It was a contained space, like a camp.

I grew up in this environment, which was paradoxically a very happy childhood. I mean, as a child you don’t fully understand what’s happening around you. What I saw was that it was a small place – everyone supported each other, all the women in the neighbourhood were like mothers to us. All the fathers were soldiers, and you had this war communism going on. Everybody had the same amount of money, same ration cards to buy the bread.

Women queue for water in a camp for displaced persons on the outskirts of Nicosia, c. 1964. Photo: Private archives

We grew up in a camp with a sort of relative equality or egalitarianism imposed on us. For instance, the rents were the same. You couldn’t rent out your house for a higher price, because there were many displaced people who moved into this enclave. We were staying in my grandmother’s house, four families in one house, for example. All the relatives were crowded into one house. My childhood was like that. For me it was happy, but of course I didn’t know the other sides of the war.

You could hear now and again the guns and shooting. There were uniformed soldiers everywhere. I was too young to be conscripted, but I experienced the explosion of masculine military culture all around me. My father, my uncles, my cousins, they all became fighters, because that was the norm: being a man meant to carry a gun and become a hero for your community and defend your people. We grew up in that kind of environment. There were Turkish flags and Turkishness everywhere. And I didn’t get to know a single Greek Cypriot until I went to London. Can you imagine? This is like 18 years.

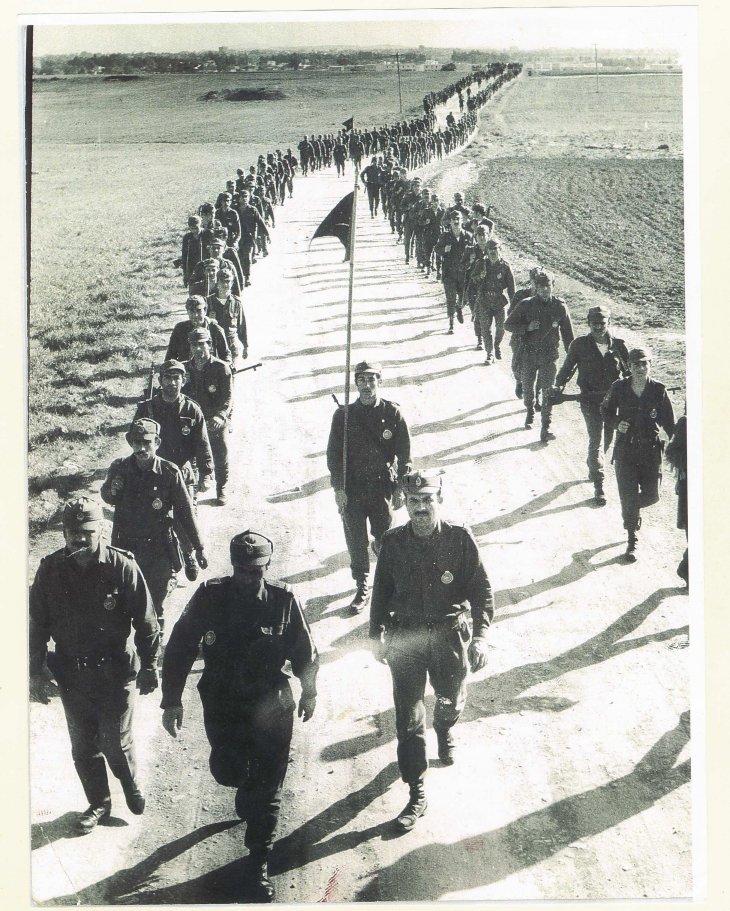

The Turkish Cypriot guerrilla organization, TMT, transformed into a standing army in 1968, primarily tasked with protecting the enclaves. Mete’s father, Özer Hatay, is the first man on the left. Photo: Private archives

We used to watch the Greek Cypriot kids from a distance. There was one apartment building in my neighbourhood, and we used to go on top of that and watch them playing football and everything. We were also obsessed with barricades and territory, so we developed games about borders, like trying to fly our kites over to the Greek Cypriot side without losing them.

The siege was lifted in 1968, and after that life was a bit easier. We used to go with our mothers and fathers outside the enclaves, for instance to do some shopping very quickly. But you never got to know anyone. Also, Greek Cypriots still couldn’t enter the ghettos. It was an environment like that.

The Cyprus Partition

Then 1974 happened, and we saw all the other tragedies happening to Greek Cypriots this time. On our side, there was a lot of joy when the Turkish army entered the city. But soon we started seeing lorries loaded with prisoners passing through our neighbourhood. I was twelve years old then, and I observed all this. Some of the lorries were also loaded with dead bodies. I saw planes bombing certain neighbourhoods. Wounded people. Both Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots. All this suffering that you observe, that you witness in the war.

After that, there was another period of looting. Turkish Cypriots got out of these ghettos, they moved from three percent to 30 percent of the island, and started looting everything. So that was the other tragedy. Growing up with all this, seeing victim become perpetrator, perpetrator become victim – seeing them change places depending on the situation – triggered a lot of questions in my mind. But of course, it wasn’t a systematic thing.

I stayed for five years on the divided island after 1974. In these four, five years, what I observed was very interesting. We moved into a Greek school, for example. The previous school was a former matchbox factory, and from this matchbox factory we moved into a proper school with microscopes and a library and things like that. It was social mobility for all the Turkish Cypriots. They went from being a neglected little group to being the masters of all this loot that was left behind by the Greek Cypriots. And even our school was a looted place. Then we saw this former cigarette factory, which belonged to a Greek Cypriot man, being turned into a parliament, and it is still used as a parliament.

Then, when I was 17, I went to study in London. I went to study hospitality management because tourism would be the future of the northern part of the island. Then I moved to Vienna for a while, and came back to Cyprus again in 1988. I was away for nine years or so, and the moment I stepped off the boat the police stopped me, because I hadn’t done my military service. I had just come back to see my home and family and they immediately threw me into two years of compulsory service.

In many ways, it was the worst time of my life. I was also older than almost all the other conscripts and was used to living on my own. You’re put in a room with another 40 guys, in this fascist environment where you can’t ever ask ‘why’ and just have to say ‘yes, sir’. Of course, militaries everywhere must be the same, but when it’s compulsory and you’re forced into it, it hurts more.

After I finished my military service, I didn’t have the courage to go back to Europe and start again from the beginning. I stayed on and began working as the assistant manager in a formerly Greek Cypriot hotel, the Dome Hotel in Kyrenia. After several years, I became the hotel manager. I was there for almost 12 years, and during that time I started to observe how people live in their everyday lives with this de facto state, how they interact with its institutions and so on. It’s supposed to be your new home, your new state, but it’s always temporary. You work in a place, like the hotel where I worked, but this place doesn’t really belong to you. It might belong to you later, or it might be given back to its Greek Cypriot owner. So you’re in a permanent state of limbo, having a state that’s not a state. That caused me to develop an interest in liminality and temporality.

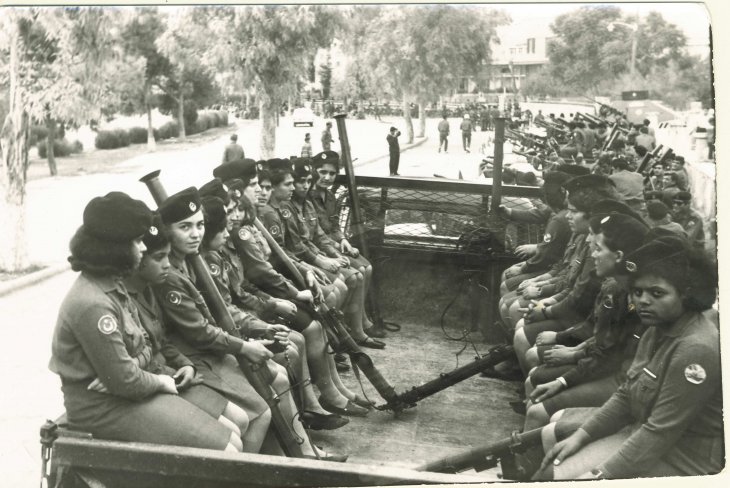

During the enclave period, women also served as fighters. Here they are pictured during a “national” parade, one of the few sources of entertainment during the period. Photo: Private archives

Increasingly, I started reading and investigating more, and meanwhile I started teaching in the Tourism Department of Near East University. I began conducting independent research and writing in local newspapers and magazines. Gradually, I became well-known in the north for my investigative journalism. This was around 2000, but of course I should also talk about the background to this period. The 1990s was the time after the Soviet Union collapsed, the Berlin Wall came down, and initially in this post-Cold War period there was this enthusiasm on the part of the international community to solve conflicts all around the world.

This was when Cyprus also came onto the agenda of the international community. In the post-Soviet period, and also right after the Belfast agreement, the international community said ‘OK, it’s time for Cyprus to be solved’. And in that period, the US and the EU created a linkage politics, the plan being for Cyprus to be united and join the European Union and Turkey to get a date for negotiations on joining. And the US and EU started pushing for a solution. The negotiations were intensified. Civil society was motivated and started growing in north Cyprus.

Becoming an Activist

During this time, Turkish Cypriots had two big crises. The local banks collapsed in 1999, and then in 2000 there was an economic crisis in Turkey that hit the north. The Turkish lira was devalued overnight. There were a lot of people in the streets striking or protesting against the government and Turkey. All these protests gradually turned into a peace movement in 2002, when Mr. Annan or Desoto – his good offices guy – dropped a peace plan on the table. This very soon became known as the Annan Plan.

Of course, this was while the people were demonstrating and everything, so that again fuelled the movement. And there were huge changes in Turkey. The Kemalist regime collapsed. The Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power. The AKP came with an EU agenda, which also included solving the Cyprus problem, and intentions to find a Belgian model for Cyprus. They were open and supportive of the peace movement in Cyprus, so the environment changed.

In 2001, I quit my job and became a full-time activist, collaborating a lot with Greek Cypriots, abroad or in the buffer zone area. We were preparing different ideas to solve the Cyprus Problem, having discussion platforms and so on. During this time, PRIO arrived in Cyprus. I think it was [Jan] Egeland’s idea to help the process in Cyprus somehow.

First, PRIO sent someone from Norway in 1998 to establish a discussion group for people coming from different professions and backgrounds. You had politicians, businesspeople, teachers, and activists participating from both sides of the island to come up with alternative Track 2 ideas to support the Track 1 diplomacy. In 2000, PRIO sent Trond Jensen, who established another group called the Dialogue Forum. This was when PRIO opened an office right in the buffer zone with just Trond and his secretary.

Then we were invited in. I was then helping with logistics for the Uppsala Initiative run by Ann-Sofi Jakobsson in Cyprus. We were arranging four-party meetings between Turkey, Greece, Turkish Cypriots, and Greek Cypriots. The Dialogue Forum was parallel to that – somehow it was linked – so I got involved with PRIO more and started helping Jensen out in the north. Because the borders were not open yet, he could cross for a day until five o’clock in the evening, but he couldn’t stay here. So we were helping him out in this isolated period.

After the UN presented the Annan Plan to the leaders, some of us from the Dialogue Forum sat down and came up with an idea for an information campaign about the plan. That was Yiouli Taki, a sociologist, Alexis Alexiou, Ayla Gürel, and me. We were inspired by the Good Friday agreement, and how they conducted their information campaign before the referendum. We asked Trond Jensen whether PRIO could help us with this project, to inform people before the referendum. Because we knew that the plan could be left orphaned or hijacked by politicians, and we expected there to be a lot of misinformation about the plan. So we got together.

We got support from PRIO – then under the directorship of Dan Smith – we got funding from the UNDP, and we got the blessing from all the diplomats on the island. Also, the United Nations helped us to summarize the plan, because the plan was hundreds of pages and you couldn’t expect ordinary people to read this plan. And it was changing all the time, because the process was still ongoing.

You had Annan Plan I, Annan Plan II, Annan Plan III, Annan Plan IV, Annan Plan V, yeah? Different stages. Then, meanwhile, in 2003, the borders were open, so the four of us could meet freely. We started using the PRIO office. Then Trond Jensen went back to Norway, and Ayla and Yiouli started managing the office in the buffer zone, so it became a local ownership in that sense.

This project was very successful. Soon everybody knew about what they called ‘the green books’. We prepared a 20-page citizen guide for the Annan Plan with graphs and everything, explaining how the federal system is going to work, how the property issue will be solved, and so on. And in the north, we had television programmes for a year, two nights a week, explaining the plan to people. This included a programme where people would call and ask how the plan was going to affect their personal situation, because everybody had different expectations and different problems in relation to a solution. There were displaced people, non-displaced people, citizens who were Cypriot, citizens who were not Cypriot, non-citizens, and so on. Everybody had his or her own Cyprus problem. So, people would call in and ask questions on live TV programmes, and we would explain how the plan would affect them.

The good thing about the summary was that it was written by both sides together and with the input of the United Nations, so it was a common manuscript. It wasn’t bits you select to convince Turkish Cypriots or selective bits that you take from the plan to convince Greek Cypriots. It wasn’t a ‘propaganda manuscript’: it was an actual summary. It was convincing to have it. No one could challenge it, not those who were against the plan or those who were for the plan but were also exaggerating it.

Because some citizens saw the plan as the satanic verses, some citizens saw it as the bible. So, we had to come in between, to show what it really was and prepare people for the new changes. It took us almost one and a half years to do all these things. It was successful in the north, more than in the south. Because in the south the public space was immediately taken over by the officials, and they didn’t allow Yiouli or Alexis to talk on TV or distribute booklets, have meetings and everything. But in the north, thank god, the atmosphere had changed. Both the government in northern Cyprus and in Turkey had changed. As I said, the AKP party was supporting a solution. The AKP party then was different than today’s AKP party, of course.

Then, in the north, we had this campaign, an information campaign. We went to 58 different remote villages – we had television programmes, conferences, seminars, etc. Civil society really supported us, and all that support meant that voter turnout in the north was high. The yes vote was 65 percent, so it was a successful thing. After the collapse of the referendum, having only one side voting yes in the referendum, there was this pause. The international community didn’t know what to do, because everything was linked, and this linkage was broken. They were expecting Cyprus to enter into Europe united, but the island was still divided.

PCC Staff 2006. From left: Gina Lende, Guido Bonino, Costas Constantinou, Yiannis Papadakis, Ayla Gürel, Mete Hatay, Arne Strand, Olga Demetriou.

Then, PRIO wanted to continue. During this period, Stein Tønnesson was the director of PRIO. He was as enthusiastic as us. Because he also knew how important impartial information is in conflict resolution. How things can be hijacked easily, and how certain established ‘truths’ can damage the whole process. Because there was all this smear campaigning during the referendum, during this polarized period, and there were ten different versions of the Annan Plan being presented by different sides. So, it was good to have this third space in a conflict area, the PRIO Cyprus Centre, to create a platform for more healthy debate. That was the idea. And we also requested to have a Centre like that.

The PRIO Cyprus Centre

The Centre was established in 2005 with two Greek Cypriots – Yiannis Papadakis and Costa M. Constantinou – and two Turkish Cypriots – me and Ayla Gürel – as consultants on both sides, as well

as one director from Norway, Gina [Lende], and one non-Cypriot office manager, Guido [Bonino]. Soon after, Olga Demetriou joined us, after Yiannis went back to university.

We tackled all the issues that had been demonized or securitized during the talks, and which became taboo things to talk about. Usually the liberal peace movements do not talk about triggering issues. We actually went into the controversial issues, you know? We aimed to open debates about certain things. Because both sides have to deal with a lot of denial, preventing them from seeing certain things and talking about them.

The past is always prevailing in the discussions. Whatever you imagine for the future, you always construct it from the past. And you cannot say, ‘let’s put the past behind us and start now’, because the property title still comes from the past. You cannot say to the Greek Cypriots: ‘All right, I’m keeping the property, let’s put the past behind us’, you cannot do that. Rhetorically, of course, you have to start a new life, but in reality, you always have the past haunting you – physically as well as emotionally, both through legal means, and in how history is written.

In order to tackle these problems of the different pasts, and different visions, and different truths, we didn’t say that we’re going to establish the actual truth, but at least we were aiming to prepare a third space for multiple perspectives.

So, we started concentrating on that. I wrote my report on north Cyprus’s demography, for example. It was a taboo subject to talk about demography, because one side insisted that immigration to the north is demographic engineering, and the other insisted that it was just a normal immigration. Writing about the politics of demography was taboo. In many ways it still is, though not as bad as before. And we realized after a while that our input in the discussion started changing the hegemonic narratives on both sides. Politicians and officials who had just been repeating the same lines for years suddenly couldn’t do that so freely. They could see that they could be challenged. First, those officials attacked us, both sides. But then, they had to tolerate us. Now they have this antagonistic tolerance towards us, the officials. Because we don’t follow their truths.

Creating a third space – everywhere, not in the limited ways I’m talking about – helped to increase the scope of debates; more quality debates started. We brought many people from abroad, we did many comparative studies with other conflict areas, we enabled Cypriots to see themselves as not being unique. There are a lot of similarities with some other places.

Parade within the Nicosia enclave on a “national” day. Photo: Private archives

We published dozens of reports, and we established, in a way, a credible channel on Cyprus studies, on three main pillars: one, an academic pillar, with many of our studies published in academic journals, discussed in academic arenas. Two, a policy pillar, as we are constantly being consulted by members of the international community, diplomats on both sides and such. And the third pillar is public outreach, where we use television, interviews, programmes, documentaries, radio shows. We all write popular articles in the newspapers.

This information campaign, which started in 2002, turned into a Centre in 2005. It’s a hybrid centre. I wouldn’t call it a 100 percent research centre. I wouldn’t call it a think-tank. I wouldn’t call it an NGO. It’s a mixture of everything. I think it’s a unique experience. It is a project from outside, but it is very locally owned, as we decide on our managers, and we employ them – with the collaboration of PRIO, of course. So, there is a great deal of local ownership.

We set our own agendas. Many reports are co-authored. It is amazing to have a Greek Cypriot researcher and a Turkish Cypriot researcher writing an article or report together. Or the collaboration may be between someone from outside and someone local, because we have a huge local knowledge, but sometimes it can be too much detail, and you need an outsider to put it in context. We do a lot of comparative work nowadays, also regionally.

It’s going to hopefully be a place for scholars from abroad to come and collaborate on local and regional issues. The advantage of Cyprus for research is that it’s a part of the European Union, but it’s also near to all these conflict areas. And all conflicts around the area anyways are connected to Cyprus somehow.

Wow, great. Thanks. One of the things I was interested in hearing more about is when you said: ‘In 2002, I quit my job and I became an activist’, which sounded like it was a simple thing you just decided.

Could you tell me more about what you were thinking at the time: were there any particular triggers? What made you take what to me seems a big decision?

As I said, it was a transition period. Everything was changing in the area. In Turkey, things were changing. The crises were there. And also, there was this feeling of being locked up in a place. And the prospect of the European Union was ahead of us. That train was leaving in two to three years’ time. Of course, I had more experiences before with bi-communal groups in the 1990s, in the post-Soviet period and after the Berlin Wall collapsed. The leftist people were invited into these bi-communal talks more than before. The Cold War was over. The American-funded civil society and these kind of liberal peace gatherings started including the left as well. Not just official representatives from both sides, but more persons who were opposing their own regimes. I met a lot of my Greek Cypriot friends in these meetings, so these kinds of gatherings were important for having access to the Greek Cypriot side, and to get to know some Greek Cypriot activists.

Of course, after a while, after that purpose was served, it didn’t get anywhere because you become friends and after a while you don’t produce more creative ideas. It is good to have debates, to have interaction, and then the creative ideas come. After a while you become good friends, and as I said the Americans were insisting on not talking about hot issues, like ‘don’t say occupation’. No, let the guy say occupation. All these – what they called ‘sensitive’ – words should be avoided. After a while, it just becomes friends meeting in the buffer zone or abroad.

So, I had about ten years of experience with these groups before 2002. Then, when the protests and so on started in 2002, I realized it was the turning point and it didn’t mean anything to have a normal job, you know what I mean? Everybody realized that we were in this state of exception, and we had to finish that somehow. A lot of people joined, like Ayla quit her job, I quit my job, and it became more like a full-time activity to put pressure on the government. To gather people for the peace movement. It looked like a noble cause back then, and it was in a way.

It was one of the happiest periods in my life. Because you had a purpose, you were working towards something, achieving something. These small things first, then later when we succeeded in getting the government to open the gates, for example, after all these protests. It was like euphoria, you know? Imagine after 30 years, all of a sudden, the checkpoints were open and you had flocks of people coming from the other side. It was a very interesting period.

Who Is ‘the Other’?

One other thing I’m really interested in is that you mentioned this was a collaborative effort with Greek Cypriots, as early as in the 1990s. But at the same time, when you started your story, you said that until you were 17 you never really met a Greek Cypriot, and that as a small boy, you were brought up with this idea that you had to defend your community and I guess also with particular enemy images.

So, what happened in that process? How did you make sense of who this ‘other’ was?

I mean, I started reading. And living in England helped me a lot. While you are studying, you work in restaurants and everything, and I met many Greek Cypriot refugees there in London. So, I started hearing the other side of the stories. Like I met a guy, Demitrios, he was 67 years old and he was a waiter in a Jewish restaurant in Golders Green. He said he retired at the age of 60, went to live in Varosha [in Cyprus], and then after six months the Turkish army came, and he lost everything. Stories like that.

A fighter in the Tylliria region rests with a Turkish saz, c. 1964. Photo: Private archives

And I had a friend, Andreas, a photographer. I remember in the 1980s, when we were having a drink in the bar celebrating the proclamation of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), how angry he got. Because we heard that they proclaimed a state in Cyprus in 1983. A couple of Turkish Cypriots said: ‘We have a state now!’, and he was so upset, and he didn’t talk to us for months. In a way, all this interaction in a neutral zone like London helped us to understand each other.

Then when I came back to Cyprus – I have other hobbies like making music – when I made my first CD in 1995, the music reflected all these changes. It was called ‘The Others in Me’, and it was a very Cypriot album. I had started questioning Turkish Cypriot-ness, and it was not just me. During that period, a lot of literary activities started questioning the idea that we live in a state taken away from other people. And also, the hope of getting recognized was gone by 1990. So then you start questioning.

You become like a diasporic person in your own homeland. The house you’re living in doesn’t belong to you. The state you call your own can dissolve anytime. So, you start looking for a homeland. In the old days, people used to migrate to Turkey for a homeland. As diaspora, you always have a nostalgia for homeland. In this period, we developed the notion of a united Cyprus as a homeland. Many poets and writers, we were all influenced by that, as well as people older than me. I had my contribution as well. So that changed me a lot. And a lot of people during that period. And we started pushing people – not pushing, trying to encourage people – to think about a united Cyprus more.

And as I said, there was the economic crisis. In Turkey, there was a war going on with the Kurds in the southeast, which had spill-over effects in Cyprus. You had more paranoia with the regime and everything. There was one journalist killed, a couple of bombs exploding. The establishment had started to panic, but also the opposition started to grow. This was changing, and people like me who were more liberal moved on to become more leftist.

You describe it as a natural thing, but I still find it quite remarkable. On the one hand you need to be open enough to really listen to the other side’s arguments and listen to their grievances, and on the other you need a willingness to resist the criticism and accept the risks involved in having this position, right? I don’t know how exceptional it was at that time, but I’m sure there were plenty of people who totally disagreed with you engaging in this way.

First, there was a lot of pressure, there were many attacks in the newspapers and the media. And the other thing: I quit my job, but it was intolerable after a while to work, because they sent me a letter saying ‘you have to stop doing these bi-communal meetings’, for example. I refused it. Then the civilian affairs office of the military asked me to come in. They didn’t do anything, but they were showing that they could do something if you push too much. The atmosphere was toxic. You do become a bit paranoid. Our phones were tapped, and sometimes there were civil police when we went to have meetings in villages, but also sometimes you can imagine these things.

Yeah, so you have to be quite convinced that what you’re doing is the right thing.

A destroyed Greek Cypriot cemetery in the town of Lapithos/Lapta, now in the island’s north. Photo: Private archives

A ‘Guerrilla Researcher’

Yes, exactly, exactly. I wasn’t alone. That was the good thing. You realize that it’s a mass movement, then you feel more secure in a way. Things look more doable to you when you have more support.

And then you said that you also gradually moved to becoming an academic. What did that give you?

I still don’t see myself as an academic in that sense.

And you would also not identify yourself as a peace researcher?

Yes, I identify as a peace researcher, but I like to think of myself as a guerrilla researcher. I like public engagement, which means that I respond to current events and try to shape them. I do that through media engagement that builds on my research. A lot of my journalism takes the research that I’ve done with PRIO’s support and uses it to respond to what’s happening at the moment. I also do a lot of dialogue activities and try to engage people in different ways – through film, television, music, festivals, youth gatherings and things like that. In that way, I have access to different kinds of people that I might not have access to if I were only doing academic research.

What is your unique contribution, you feel, over the years?

A lot [laughing]. I mentioned before about the taboos, the myths, that keep the conflict going. A lot of my research has been about questioning those myths. My research on demography did that. All my investigative journalism has done that. But I’ve also questioned liberal peace interventions and the formats they use, which I think just perpetuate the status quo.

I believe that there is more we can learn from vernacular stuff. I increasingly look at ordinary people’s interactions, mundane people’s everyday interaction. Especially after the checkpoints. How they reconcile without any facilitation. And how we can help these people, without facilitating them directly. Because that becomes an intervention and then it loses its organic nature. I’m looking at that because that kind of organic relationship – interaction and interdependence – is the main motor of coexistence.

Everybody doesn’t have to love each other; you can coexist without loving each other. We can find different mechanisms for coexistence, rather than this American way of reconciliation, holding hands. I felt like a guinea pig, experimented on by certain scholars coming from Fulbright who were trying to teach us how to have empathy. I can compare what should be done and what shouldn’t be. That’s why I’m increasingly more concentrated on vernacular reconciliation. As long as it’s organic, and there is some kind of need involved, and also common interest.

To have commonalities on certain things is important. Of course, we believe in multitude, but you need commonalities too. Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots can have that commonality: you find this common interest to unite people who are very different.

But that’s also an example of what you meant, how you can actually help without formal facilitation: so, you find the best jazz musicians…

No, not the best jazz musicians. Jazz musicians who are playing together, you know? They don’t have to be the best. Actually, ordinary is better. It’s a bigger group we’re talking about. These commonalities, creating common spaces. For instance, I am working now on a documentary that shows how the walled city of Nicosia has become a space for all sorts of interactions based on common interests, bringing people together.

Resolving the Problem Step by Step

Could you describe the shift of the PRIO Cyprus Centre (PCC) over time? Have you seen it change in particular ways?

The PCC is a hybrid and also a situational entity. Because its main raison d’être is the Cyprus problem, at certain times you employ different attitudes and approaches in the Centre. For example, if you have a peace process going on and everybody talks about how all the stars are aligned and you’re about to have a solution, you immediately adapt yourself to the situation. You prepare more for the aftermath: if the solution comes, what is the most urgent thing to do? Or you prepare people for disappointment. If you observe the process closely and a lot of it is only PR and you know that it’s bound to fail, you prepare people saying that, look, it’s not as presented.

Then, during a frozen period when there is no process, both sides of the island are states of exception. The Republic of Cyprus functions on doctrines of necessities, so all the Turkish Cypriots’ communal rights are suspended. And the same thing in the north: the north is a breakaway state, so all the Greek Cypriots’ rights are suspended. It’s two states of exception feeding each other. And when there’s no process, they start attacking each other. They start questioning each other’s anomalies.

For example, property issues become more important, citizenship becomes more important. So, the other party’s suspended rights and regulations become more important issues than actually solving the Cyprus problem. And in those periods, we begin to focus more on rights and regulations. These are things like the Green Line regulation that Turkish Cypriots can use to export their goods to Europe and which hasn’t been very successful because of a lot of impediments. Or the hydrocarbon issue. So, in these periods, we to try to bring the debate away from antagonism to more healthy areas, because it can get very nasty, with a lot of attacks on each other.

I have been working on this step-by-step approach to solving the Cyprus problem, rather than having comprehensive settlement talks […] where nothing is agreed until everything is agreed, which means that everything becomes a bargaining chip.

Then we also propose methods for negotiations. For example, I have been working on this step-by-step approach to solving the Cyprus problem, rather than having comprehensive settlement talks. Because with the comprehensive settlement, you postpone everything to a settlement, and you don’t do any steps meanwhile. You can have a piecemeal approach, an incremental approach. And you cannot do that with this comprehensive settlement where nothing is agreed until everything is agreed, which means that everything becomes a bargaining chip. All these issues that you could easily solve before a solution becomes a hostage to a comprehensive settlement.

Then we study settlement processes around the world, and what we can learn, like why did the Oslo agreement, the Oslo process, fail in Palestine? It was an incremental solution. But then, a lot of comprehensive settlement talks have failed as well. So where are we making mistakes, or what should the international community think of when they are jumping into a process?

Do you feel that the fact that you have both the Greek and the Turkish participation at the PCC helped in these different periods, or has it at times been difficult? Is that a method to use in other contexts as well, do you think?

I think it could be. Look, it is important to have representation from both sides, but it’s also important to have internationals or ‘non-native’ elements in the Centre to balance. Because sometimes certain personal things, even between people in a working place, can turn into an ‘ethnic’ conflict. We didn’t have that much in PCC, but I could see it in other NGOs or institutes in the buffer zone, that personal issues immediately can be turned into a ‘because I’m a Turkish Cypriot’ or ‘because I’m a Greek Cypriot’ kind of attitude. We have to be very careful with that.

De-ethnicizing the environment in the office is very important, even though we have to have these ethnic balances, but also the attitudes should be de-ethnicized. That’s why the manager is very important in balancing these things, and in immediately exposing the real problem rather than leaving it to go to these ethnic clashes.

Of course, ethnicization doesn’t always come from a person’s ethnic background. Sometimes a non-Turkish or a Greek person can act more pro king than a king. For example, our current Director Harry Tzimitras is a Greek citizen. He had been chosen for the post by our local staff (by both TC and GC staff) and PRIO director at the time Kristian Harpviken. Although Harry is of Greek origin, he has proven to be very neutral in managing the place. I sometimes find myself defending Greek Cypriot policies against Harry’s criticism [laughs]. Until him, we had only people from Oslo to run the place: Gina Lende, Arne Strand, and Gregory Reichberg. Like Harry, they also contributed positively and immensely to the centre, especially in capacity building.

Having the International Community on Their Side

You mentioned ‘the antagonistic tolerance towards the PCC from local officials on both sides’, where you felt you were increasingly having an influence. What is it that made it possible for the PCC to have that kind of influence, you think?

There is more than one reason of course. One is that the international community stood by us, which was very important. Initial attacks were resisted by all international diplomats living on the island. They saw our work, they praised our work, and they also defended our work, which was very important. But of course, this didn’t come out of the blue: they really used our work and they benefitted from our existence.

On the other hand, the academic community on both sides support the PCC, because of the good work that we do. The academic community likes us also because we prepare neutral grounds for academic debates. For example, academics at universities in the north cannot use their titles when they go to the south to participate in an academic event. But when we do it, everyone uses their own titles. For academicians, we are the third space. For diplomats, we are the third space. And for civil society, we are the third space.

What I’ve learned from conversations with two of the founders of PRIO is that this academic activism type of engagement has been part of PRIO from way back. Has this been a good thing for the PCC or has it caused challenges too?

We’ve always felt that support as a good thing. The way PRIO handled their management of the PCC has always been supportive and there was encouragement to do more activist things as well. It was not just limiting us: ‘Oh, don’t do that because the government might not like it. Don’t do that, the United Nations might not like it’. No, never. We never received any sort of intervention from PRIO; always support. As long as we do proper academic work and our work is impartial and doesn’t have any agenda apart from building peace, they are supportive. They have been supportive. That’s the activist soul that we feel from Galtung. The people we know in PRIO are the same, that is an encouragement to us.

Mete Hatay at the PRIO Cyprus Centre. Photo: PRIO

But I think there’s still a big difference, and that is that you’re actually living in a conflict, and the researchers in Oslo, most of them don’t and never have. One of the questions we ask everyone for this project is ‘what is your intellectual and emotional relation to peace?’ And I’m not really sure whether that’s the right question to ask you. Maybe it is, but you’re in such a different position.

Yeah, because we get the feedback the next day. Which has been difficult sometimes, but usually constructive. People respect us. That’s the thing we established here. That’s very important. On both sides, the media respect us. Once you become an influencer in the media, this helps you to defend yourself. They cannot get at you that easily. I can answer back.

But it is of course different than writing an academic article. The politicians here haven’t read my academic articles, but they know my newspaper articles. Which is the juice of what I write. That’s why it’s important to have this outreach I believe, to them. It also brings up the question of wider academic debates: how much can we lock ourselves in just the academic arena and not take our research back to the people? I think that’s very important.

Resolving Problems – Not ‘the Problem’

For many, many years the PCC has been trying to contribute to a solution to the Cyprus problem or to have coexistence in some peaceful way. What is your main inspiration to continue doing what you’re doing, considering we’re now in 2019, and the solution at least hasn’t been found yet?

As I said, I’m not concentrating on this wholesale solution. I concentrate on Cyprus problems, in the plural. And there are many problems in Cyprus that we have to tackle. To tackle those on an everyday basis gives me meaning in life. Because I love this country, I love this island.

But also, it means something to … for example, I have been campaigning for the Maronites to return to their villages. And initially, last year it was announced that they were going to allow Maronites to come back to their villages. To work on that and to see results coming out from your push, or from you work, that gives meaning to life. It gives you energy.

I concentrate on Cyprus problems, in the plural. And there are many problems in Cyprus that we have to tackle. To tackle those on an everyday basis gives me meaning in life. Because I love this country, I love this island.

Of course, you have a very pessimistic world order now when you look around. You see a lot of lunatics and you know, authoritarianism is becoming the general norm now in a lot of countries including in the EU. Certain countries are really changing fast, and xenophobia, islamophobia, all these phobias, even democrophobia, are everywhere. It is important to have an input slowing down this terrible change. Having a positive input in the debates on further democracy, which is a must in a sense to establish a peaceful coexistence for people.

Yeah. Of course, I phrased it wrong also, ‘the solution hasn’t been found’. Of course, it is important to think of all the small contributions you’re making. I’m doing quite some research on societal transformation and the role of individuals in it, and I think most of the people I speak to, when they manage to have this kind of inspiration and drive to continue, it is because they see all these achievements that are there, and don’t just think about the larger picture. It is depressing once you start looking on the larger levels, you might easily think ‘what’s the point?’

It’s very easy to be melancholic. It’s like the leftist melancholy after the Cold War: there is no longer revolution, there is melancholy. That’s why, instead of having one revolution, it is important to have little, little reforms, and this keeps us going until the big revolution happens, you know? So I’m always very anti-nostalgic and anti-melancholic in my way of life.

I constantly produce. I try to be a model as well for young people, without imposing myself on them. So that’s another input that I have in the society. They can see that I’m DJing, I’m writing, I’m being very critical, but on the other hand also trying to find a solution to problems rather than just whining. These are I think important things for the youth to hear. Because in Cyprus, they’re very cynical, it’s beyond melancholy. It’s a toxic societal attitude we have. Everybody says: ‘Nothing’s going to happen, nothing can happen’. Constantly.

In order to challenge that, you have to show that some things can happen. To make people believe that some things can be achieved. Sometimes a revolution, mass mobilization, is important; but sometimes you don’t have that, so you have to do your reforms in everyday life.

Really important. All right, then I wish you good luck with the DJing, and the writing and everything else.

I have a concert.

Coming up?

Next Saturday, yes.

Nice! Thank you very much, Mete.

…most encouraging.

Indeed let us not forget who died, murdered and made to disappear, those not “Greek”, and not “Turkish”, but Cypriots, for “being” Cypriot.

Like wise, let us remember that while it is “them” around which the debate revolves, it is Cypriots which suffer the injustice of its impasse.

…good reading.