I made an argument about Russia’s weakening and vulnerability in Brookings’ blog Order from Chaos, suggesting, in particular, that

What is less obvious for many Russia-watchers is that the military strength demonstrated so pompously on the Red Square during the May 9 Victory Day parade is also in decline. In Ukraine, the lack of any meaningful political or strategic Russian goals erodes the morale of the troops who are clandestinely deployed there. Nervous about the domestic political consequences of growing casualties, Putin has classified information about warzone deaths as a state secret. The costs of the war are mounting, and over-spending in the Armaments 2020 priority procurement program is yet another item in the list of embarrassing fiscal setbacks. It is clear to serious Russian economists that military expenditures have been out of control for the last four quarters at least. Such spending cannot be sustained indefinitely, and deep cuts in the defense budget are certain this year.

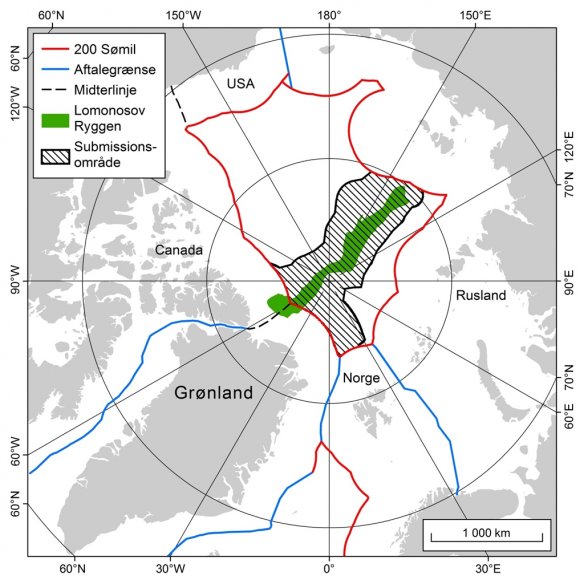

I didn’t expect this point to find corroborating evidence in the accident with a Tu-95MS strategic bomber that caught fire on the runway of the Ukrainka airbase in the Far East with the loss of life of one pilot. It is a striking coincidence that earlier this week two other accidents happened in the Russian Air Force: a MiG-29 fighter crushed during a training flight in Astrakhan oblast (both pilots safely landed on parachutes) and a Su-34 fighter-bomber had a hard landing in Voronezh oblast (the pilot was rescued). Norwegian and other NATO pilots have become quite familiar with ageing Tu-95s, and it is very fortunate indeed that the accident happened on the ground – and not during a strategic patrol over the Arctic ice, where suspicions about foul play would have inevitably exploded in Moscow leading to a further escalation of tensions.