Jihadists have succeeded in taking control of more than half of Mali, where many people in rural areas are now adherents of one armed group or another. This situation is largely the result of widespread frustration with the bad governance by the country’s corrupt ruling elites. While the jihadists have managed to take advantage of popular discontent, Western countries have shown little interest in understanding the situation. Rather, aid donors have focused on praising Malian democracy and highlighting desertification and climate change as the greatest threats to the country’s development. This has contributed indirectly to the insurgents’ success. The frustration we see in Mali may generate similar uprisings elsewhere.

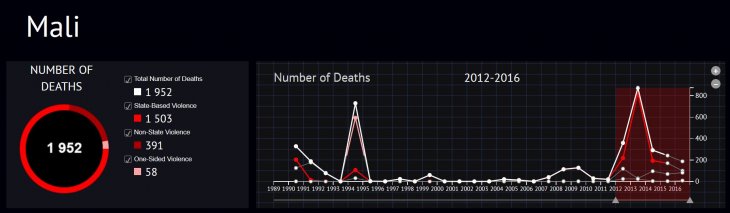

Mali has seen a surge in violent conflict events in recent years, with battle-related deaths conservatively estimated at around 2,000 between 2012 and 2016. PHOTO: Screenshot from Uppsala Conflict Data Program

Following the country’s political and economic collapse in 2012, it may take decades for Mali to regain stability. Several factors contributed to the crisis, but one trigger in particular was the bombing of Libya and the assassination of Gaddafi in autumn 2011. Following the bombing, between 1,000 and 4,000 heavily armed Tuareg soldiers, who had been serving in the Libyan army, returned home to Mali, adding fuel to a Tuareg uprising that was already simmering in the north of the country. Together with the jihadists, some of these Tuareg soldiers succeeded in advancing south, before being pushed back by a French counter-offensive in January 2013.

The frustration we see in Mali may generate similar uprisings elsewhere … The national government has become so unpopular that many see the jihadists as a preferable alternative

The jihadists have returned, however, and they now control not only rural areas in northern Mali, but also the central Mopti Region. They have gained control through a process of gradually establishing small groups in the region. These groups have attracted ever-increasing support from smallholders and, not least, nomadic herders. Meanwhile, Mali’s army and government have retreated to the cities. The national government has become so unpopular that many see the jihadists as a preferable alternative. This is despite the fact that Mali has been held up by Western aid donors as a model for democratic development in Africa.

Hamadoun Kouffa

Hamadoun Kouffa is widely considered the leader of the main jihadist group in the Mopti Region (the Macina Liberation Front). During the 2000s, a combination of external influences and trips to Pakistan and Afghanistan gradually converted Kouffa into a radical Salafist.

Although his speeches are seasoned with Islamic references, his primary message is, however, more secular. The main targets of his speeches are the ruling elites. According to Kouffa, these elites are corrupt and survive by exploiting ordinary Malians. In particular, he singles out the judiciary and the Forest Service as corrupt.

Hamadoun Kouffa. PHOTO: news.abamako.com

It is well known that the only possible way of winning a court case in Mali is to pay hefty bribes to the judges. As far as the Forest Service is concerned, its power increased significantly during the 1980s, when huge amounts of aid were channelled to fund anti-desertification measures. While other areas of the state administration suffered cutbacks due to structural adjustment, funding to the Forest Service increased many times over. Local Forest Service personnel were given sweeping powers to levy fines or arrest people for offences such as collecting dry wood or owning too many goats. These powers were enforced with the assistance of international aid given to promote sustainable development, and accordingly to combat desertification.

Kouffa realizes the power of playing on people’s grievances, and often makes particular reference to the Forest Service in his speeches about corruption in the state administration. In addition, Mali’s herders have long felt increasingly marginalized due to shrinking access to grazing land, as pastures have been converted to agricultural fields, often as part of large, state-run projects. This has led to many conflicts between herders and farmers, particularly in the Mopti Region.

Siding with the herders

Various jihadist groups in the Mopti Region have won many new members in the last two to three years by siding actively with the herders. Meanwhile the army often supports the sedentary farmers in these conflicts.

During my regular visits to Mali during the 2000s, it was curious to witness the contrast between the domestic debates about corruption and bad governance and Mali’s international image as a beacon of successful African democracy. The fact that Mali’s democracy was disintegrating either went unnoticed internationally or was deliberately ignored.

Mali’s herders have long felt increasingly marginalized due to shrinking access to grazing land … This has led to many conflicts between herders and farmers

Misinformation about desertification

There is a widely held view that there is a close connection in the Sahel between climate change, desertification, conflict and the current refugee crisis. This is despite the fact that rainfall has increased since the drought of the 1980s and the Sahel is greener than it has been for many decades. In this way climate change has contributed to divert attention away from the real political causes of Mali’s problems. By erroneously lending support to an ever more unpopular and corrupt government, aid donors have contributed indirectly to the growth of jihadism.

In the early 2000s, groups linked to Al-Qaeda began to arrive in Mali from Algeria, where they had been on the losing side in the civil war. Slowly these various jihadist groups boosted their positions in northern Mali. Some raised a great deal of money by smuggling cigarettes and cocaine across the Sahara, as well as by hostage-taking. Millions of euros were paid in ransoms for European hostages, and Malian government officials often took large sums for acting as intermediaries.

Jihadism and NATO bombings

To summarize, the crisis in Mali is the result of several unfortunate circumstances, such as the growth of global jihadism; NATO’s bombing of Libya; deep-rooted discontent among many Tuaregs, as well as increasing frustration among other ethnic groups; increasing corruption; and the fact that aid donors presented Mali as a success story, while ignoring popular discontent. While aid donors focused on climate change, the growing anger at the ruling elites in Mali was completely ignored. In turn, this provided fertile ground for recruitment by jihadist groups, allowing them to take control of more than half the country.

Today Mali is “hot” in international aid. The refugee crisis, jihadism and climate change are attracting the attention of Western donors, who are queueing to donate aid to Mali. There is a distinct lack, however, of good ideas as to how to spend funds in order to resolve the crisis.

No quick fixes

There are certainly no quick fixes for the situation in Mali, and the country’s crisis will most likely continue for many more years, perhaps decades, to come. In addition to the unforeseen consequences of the bombing of Libya, the crisis in Mali has one important lesson for the aid sector: it is important to pay close attention to what is happening in the population at large.

In particular, access to land and natural resources have an inherent explosive force that could generate similar crises in other countries. Over the past decade, the struggle for Africa’s resources has intensified. In many places, this has caused smallholders and herders to lose control over land and resources as a result of, for example, major investments in agriculture, the establishment of nature reserves, or mining.

To summarize, the crisis in Mali is the result of several unfortunate circumstances, such as the growth of global jihadism; NATO’s bombing of Libya; deep-rooted discontent among many Tuaregs, as well as increasing frustration among other ethnic groups

The frustration that is building up among the rural populations of several African countries may trigger popular uprisings similar to the one we are now seeing in Mali. The form such uprisings take may be more or less a matter of circumstances. In Mali and some other West African countries, jihadism has emerged as an opportunity that many people have opportunistically latched onto. In other cases, such uprisings may be based on ethnic or party-political divides.

This blog post was originally published in Norwegian as an opinion piece at Bistandsaktuelt.

Leave a Reply