Minimizing loss and damage from climate change is a major societal challenge for developing and developed countries alike. In order to understand how climate change may affect vulnerable societies in the future, the climate change research community has developed five complementary scenarios of future development, the so-called Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs).

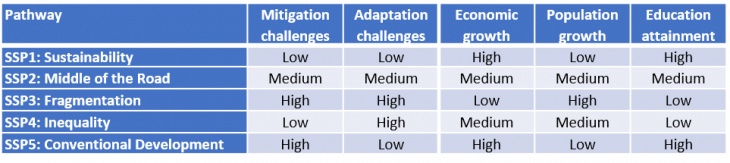

The five SSPs are not competing for accuracy but rather designed to constitute stylistic representations of alternative development pathways, intended to jointly capture the plausible ‘probability space’ of future changes in countries’ socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1. Global characteristics of the five SSPs (see here for the original version).

SSP3 is considered the most pessimistic scenario, denoting a future world with high population growth, slow improvements in educational systems, and poor economic growth. In this world, challenges to climate adaptation and mitigation are high. SSP1, in contrast, represents a relatively optimistic future, with higher socioeconomic growth rates and rapid transition into renewable energy consumption, implying low barriers to both adaptation and mitigation.

The economic growth projections underpinning the SSPs are based on a classic economic model that is known to perform well for large, developed economies. Unfortunately, this model performs much less well for developing countries, in part because it fails to capture the likelihood of growth disruptions. Instead, economic growth is assumed to follow a logic of conditional convergence, whereby poor countries gradually catch up with wealthy economies, provided sustained improvements in education levels.

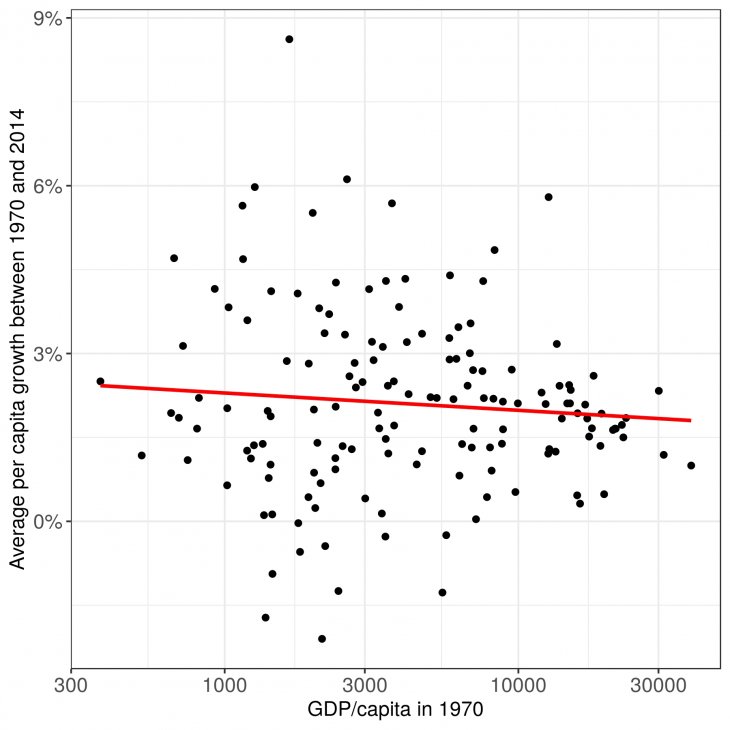

In the real world, macroeconomic growth fluctuates markedly, especially among developing countries, and we find little evidence of the assumed convergence mechanism. Figure 1 plots the average growth rate of all countries between 1970 and 2014 as a function of their level of development in 1970. As indicated by the near horizontal red line in the plot, the poorest countries at the outset of this period have been growing as fast as—but not much faster than—rich countries on average, but there is much greater variation in growth rates among lower-income countries.

Figure 1. Average economic growth rate by level of GDP per capita in 1970.

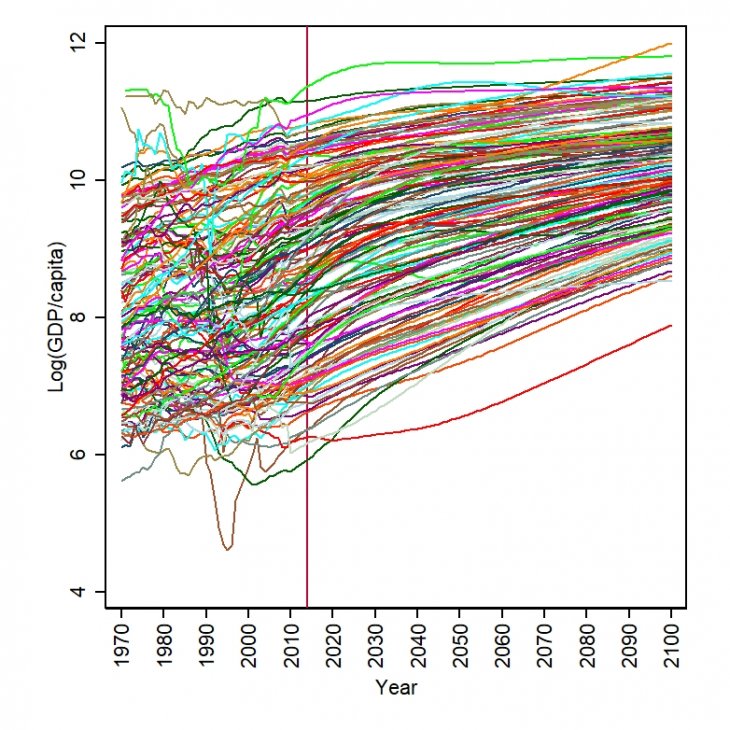

Despite weak indication of convergence in the past, all but one of the 15 growth projections in the SSP framework (three modeling teams provide alternative projections for each of the five SSP scenarios) feature strong convergence between the poorest and richest economies. As a consequence, projected future growth in poor countries vastly exceed experienced historical growth rates even for the most ‘pessimistic’ SSP3. For countries with GDP per capita below USD 1,000 in 2014, projected average economic growth until year 2100 is 3.2% per year. By comparison, the average yearly growth rate between 1970 and 2014 for these twelve countries was 0.1%.

…projected future growth in poor countries vastly exceed experienced historical growth rates even for the most ‘pessimistic’ SSP3

Figure 2. Historical and projected future level of GDP per capita (SSP3).

Figure 2. Historical and projected future level of GDP per capita (SSP3).

An important reason for the notable break between observed and projected growth rates for poor countries is the economic models’ implicit assumption of undisturbed growth. Common causes of growth disruptions, that remain unaccounted for in the quantified SSPs, include commodity price shocks, distortionary fiscal policies, political instability, and, notably, armed conflict, all of which are much more prevalent in poor countries.

The consequence of this deficit is that the range of futures provided through the SSP framework covers a too small area of the conceivable probability space due to an overly optimistic lower band of growth projections. Of particular concern is the fact that the countries for which the GDP projections will fit the least well are the very same countries where vulnerability to climate change is considered the highest and for whom sound adaptation and impact assessments may be most in demand. Inflated growth projections for the least developed countries signal unrealistic reductions in vulnerability and may result in too modest loss and damage estimates, thereby undermining material incentives for choosing a sustainable development pathway over less stringent emission policies.

Inflated growth projections for the least developed countries signal unrealistic reductions in vulnerability and may result in too modest loss and damage estimates, thereby undermining material incentives for choosing a sustainable development pathway over less stringent emission policies.

Although modelers need high-growth scenarios, and there may be compelling reasons to remain optimistic about the future, sound and comprehensive impact assessments also require projections that are at least as pessimistic as the recent past. Therein lies an important challenge for the scientific community. By bringing the political context explicitly into the SSPs, researchers will be better positioned to provide decision makers with scientific information required to identify optimal climate policies.

[…] In a new article published in Global Environmental Politics, Jonas Vestby and I show how common socioeconomic scenarios, used to evaluate (among other things) the human and material cost of alternative climate change futures, suffer from a too optimistic underlying economic growth model. The result is that assessments underestimate the relative burden for developing countries of maintaining business-as-usual as opposed to shifing to a more sustainable development pathway. A blog post commenting on the article is available here. […]