Human migration driven by weather variability and environmental change (see, e.g., here, here, and here) has been identified as a possible link between global warming and violent conflict (see, e.g., here, here, and here). Despite academic and public policy discussions about these and similar topics, the relationship between climate change and regional migration within developing countries remains understudied in relation to the risk of violent conflict (although there are notable exceptions).

In addition to tensions among communities related to cultural or religious traditions – in their own right a potential source of hostilities – plausible sources of animosity between host and arrival communities include housing and job market pressures, changing electoral demographics, and access to public goods (e.g. primary schools and other services).

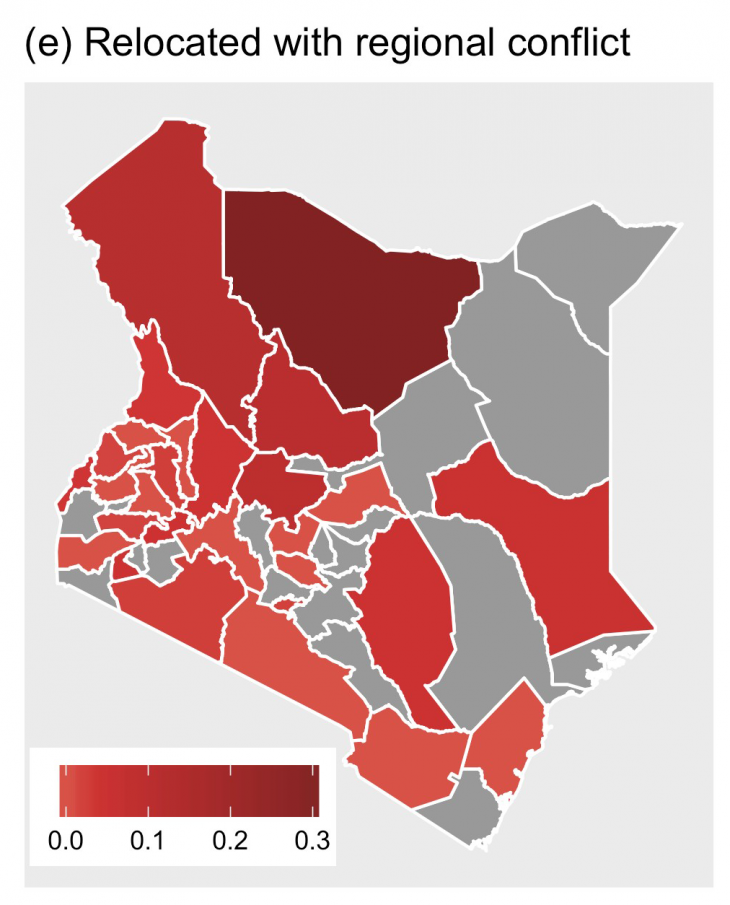

Share of drought-displaced respondents in Kenya who reported host-migrant hostilities. SOURCE: Linke et al. (2018)

The relationship between climate change and regional migration remains understudied

Even if a region’s population increases over time and this correlates with the risk of violence or political instability, any reporting of a relationship between the two contemporaneous changes is based on the assumption that conflict is either perpetrated by migrants against hosts or committed by long-term residents of an area against new arrivals. If this assumption is false, violent events could take place between people who have no direct personal experience relocating in response to drought or interacting with people who have.

Valuable recent research reports Indian state’s prevailing political alignments vis-à-vis the central government to determine whether the likelihood of riots increases when migrants fleeing drought elsewhere arrive. However, the authors use state level data instead of speaking with migrants directly and treat climatic shocks primarily as a corollary statistical instrument for their main argument about formal institutions and nativist politics.

With colleagues Frank Witmer, John O’Loughlin, Terry McCabe, and Jaroslav Tir, I recently published an article in Environmental Research Letters that uses original Kenyan survey data to avoid problematic assumptions about peoples’ behavior and attitudes as part of broader population dynamics. We asked respondents directly about their experiences as they relate to drought or water shortages, temporary and permanent relocation, and conflict. Alongside other innovative migration research, our research speaks directly to one of the many potential mechanisms operating between environmental change and conflict.

Members of the Institute for Development Studies, University of Nairobi, survey enumeration team near Eldoret, Kenya. PHOTO: Author

In a sample representative of all regions in Kenya (1,400 respondents across 175 enumeration areas), we find that people who report relocating due to drought are at greater odds of experiencing violence than the general population. Furthermore, this risk varies according to the status of their move. Respondents who moved temporarily and those that relocate into the traditional area of other ethnic communities have the greatest risk of victimization.

People who report relocating due to drought are at greater odds of experiencing violence than the general population

We followed this analysis of victimization risk with the more ambitious goal of understanding whether Kenyans were more likely to support the use of violence based upon their experiences. Because of social desirability bias – respondents are highly unlikely to admit to our survey enumerators that they approve of using violence – we used an endorsement experiment methodology (similar to this study), designed specifically to elicit honest responses to sensitive questions. Our respondents who reported moving are no more likely to express latent support for the use of violence than the general population. Interestingly, there is a conditional impact of having relocated due to drought and also being attacked. A combination of these experiences is associated with higher levels of support for the use of violence.

Our findings bring us a step closer to understanding how one of the most plausible mechanisms linking climate change and conflict operates in sub-Saharan Africa. Our general conclusion is that migrants are a vulnerable population and their maltreatment stands to make a troubling problem even worse.

Our work is not without limitations. We were too concerned with misappropriation to inquire about the identity of the attack perpetrators. Such research will only add additional detail to our main finding that migrants endure tenuous, risky, and precarious conditions as they negotiate livelihood uncertainty in the face of climate change.

Leave a Reply