The increase in global temperatures by over 1 degree Celsius since pre-industrial times is already having broad and significant impacts. An ongoing multi-year drought in Eastern Africa, for instance, has been attributed to global warming. Hunger crises, displacement, and exacerbated conflict between pastoralist groups are some of the reported dire consequences. This blog post reports on a recent study of the consequences of environmental hazards for attitudes toward violence in Uganda. The story was originally published by New Security Beat.

The past several years have led to greater recognition of climate-related threats. Most recently, Malta, Mozambique, Switzerland and the UAE made a public pledge to championing climate change within the United Nations Security Council. While a comprehensive resolution on climate change as a threat to peace and security has yet to be adopted, climate change impacts on instability have already been acknowledged in multiple UN Security Council resolutions on UN missions, including those addressing ongoing armed conflicts in DR Congo, Iraq, Somalia and South Sudan.

Indeed, existing research indicates that regions already affected by conflict are particularly vulnerable to seeing increased risks in various ways. This vulnerability is manifested not only in conflict-affected populations being more sensitive to droughts, storms, or floods, but also in the so-called conflict trap. This trap encompasses widespread poverty, erosion of trust, and the availability of weapons and armed actors due to ongoing conflict, causing violence to perpetuate itself. Climate-related hazards can further exacerbate the economic dimensions of this trap.

Understanding how and why these patterns come about is a gap in current knowledge, however. Can we go beyond these general observations of climate-related fragility, and understand the specific conditions under which individuals in such areas resort to arms? In-depth systematic studies are rare. Yet addressing this gap is important not only to provide critical evidence on pathways to conflict, but also for informing how to mitigate such risks.

Floods, Insecurity and Violence: The Case of Karamoja

In a newly published article in Regional Environmental Change, my co-authors and I address that gap with research using household survey data from the Karamoja region of northeastern Uganda. Karamoja is not only one of the country’s most food-insecure regions but has also been plagued by communal violence and violent cattle rustling for decades. After a prolonged period of relative peace, the region is once again facing major insecurity.

Piloting UN FAO-led survey data collection near Moroto in Karamoja, Uganda. Photo: Nina von Uexkull.

Drought has received major attention in climate security research—and it is also the kind of hazard that is often associated with Eastern Africa. But we chose to zoom in on the exceptional regional flood that hit Karamoja in 2018. The implications of floods for conflict have received little attention, and constituted a way to fill in this particular gap in research on climate insecurity.

We found that flood exposure was associated with greater support for the use of violence

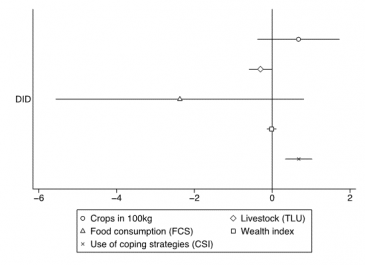

What were our conclusions? We found that flood exposure was associated with greater support for the use of violence among respondents. Comparing individual changes in responses before and after the flood, we observed that flood not only had adverse impacts on livelihoods and decreased livestock resources but also increased the use of coping strategies and shaped respondents’ attitudes toward the government.

Figure displays flood impacts from difference-in-differences (DID) estimation, comparing trends among households that were flood exposed to those who were not. Households exposed to flood lost livestock and increased their use of various coping strategies.

We were not able to link these changes to increased support for violence in subsequent causal mediation analyses, however. But this new body of knowledge does highlight the importance of climate-related hazards in conflict-affected regions, as well as the complexity and context-specific nature of the relationship between climate-related hazards and conflict patterns.

Creating Synergies

The usefulness of our efforts extends past the data and conclusions of our paper, however, because our research builds on fruitful cooperation between fundamental research and practice.

Systematic micro-level data is critical for understanding the relationship between climate change and conflict. But conducting studies in conflict-affected regions is fraught with risks and logistical challenges. Academics often lack access and resources to study individual perceptions and behavior in remote and conflict-affected areas.

Systematic micro-level data is critical for understanding the relationship between climate change and conflict

Yet, important data for such studies does exist. Development and humanitarian agencies such as the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Food Program collect a wealth of data in monitoring and evaluation efforts, including in conflict-affected regions. Many resources are invested in such data collection that is fundamental for examining project impacts, but there is not always time and capacity to go beyond applied questions.

Collaboration between such organizations and researchers can result in the identification of valuable synergies. While there have been previous instances of such cooperative efforts (see examples here and here), there is significant potential for further exploration of climate-conflict connections. By pursuing more co-production of knowledge among researchers and practitioners and collaborative research along these lines, we can gain further insights into climate and security that can help inform long-term development cooperation strategies.

***

Nina von Uexkull is Associate Professor of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University and Associate Senior Researcher at PRIO. This research was conducted with support from the Mistra Geopolitics research program.

Leave a Reply