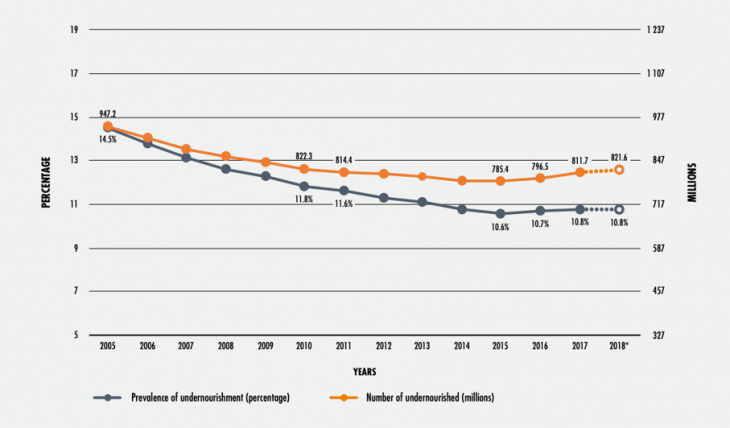

The recently concluded UN Millennium Development Goals framework documented significant progress (although not complete success) in halving the proportion of people suffering from hunger by 2015, compared to 1990. However, in the most recent years, the global rate of undernourishment has again been on the rise. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the main cause of this retrogression is escalating violence in war-affected areas. Making matters worse, the human cost of war is sometimes compounded by climate shocks, most notably drought.

Water from the Massaca Water Reservoir in Mozambique is used to irrigate local agriculture. Photo: John Hogg/World Bank/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The FAO reports that the situation is most alarming in Africa, where the concentration of food insecurity is highest, and where rates of malnutrition are increasing more or less across the board. Undernutrition can manifest itself in a variety of ways, but maternal and child malnutrition contributes to 45% of deaths in children under the age of five.

The number of undernourished people in the world has been on the rise since 2015, and is back to levels seen in 2010–2011. The dotted line indicate that the rates are projections. Source: FAO.

In order to reverse this trend, development aid is vital. Broadly speaking, development aid is aimed at increasing recipient communities’ ability to deal with shocks that have the potential to materialize in growth disruptions. Notable sources of such shocks are armed conflict and extreme weather events.

In a recently published article, my PRIO colleagues Siri Aas Rustad and Halvard Buhaug and I investigate whether official development assistance increases the recipient population’s capacity to cope with droughts across Sub-Saharan Africa. Specifically, we look at whether undernutrition rates among children after droughts are lower in areas that have recently received aid projects from the World Bank than in areas that did not.

To measure child undernutrition, we use a weight-for-height measure called wasting. Wasting captures acute malnutrition, and several existing studies show that rainfall variability, and particularly drought, increase child wasting (see for instance here and here).

In order to measure whether local communities’ resilience to drought is in fact higher in the areas that receive development aid, we first need to establish the direct association between drought and child undernutrition. To this end, we compile a comprehensive georeferenced dataset of individual respondents from 32 Demographic and Health Surveys in 16 sub-Saharan African countries. This dataset contains information on 138 103 children, which we then compare with historical data on rainfall.

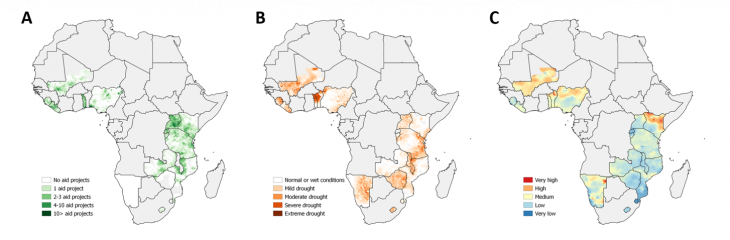

As expected, we find that severe droughts are associated with increased levels of child wasting in affected areas. The maps below show the geographic locations of three variables of interest.

Geographic distribution of World Bank aid projects (A), recent drought exposure (B) and prevalence of child wasting (C) in the sample. Illustration: Rustad et al. 2019.

The second question we pose is whether aid can mitigate some or all of the adverse health effect of drought. Because some areas are more likely to receive aid than others, we use a technique called matching to ensure that we only compare outcomes (child wasting) between invididuals that live in areas that have a similar likelihood of receiving aid in the first place.

With this, we find a positive health effect of aid projects among the children who have been exposed to drought in the year prior to the survey. This means that children living close to aid project locations are better able to cope with a near-future drought than those who do not live close to an aid project site. Among children not exposed to recent drought, the difference in observed health outcomes between aid recipients and the control group is small. In other words, there does not appear to be a general increase in nutrition rates following aid projects.

Because undernutrition is closely linked with food insecurity, aid projects that specifically target the agricultural sector should have benefits for local food and livelihood security, particularly in rural sub-Saharan Africa, where rain-fed agriculture is the dominant sector both in terms of employment and income.

Drought-resilient seeds produced by the West African Agricultural Productivity Program. Photo: Daniella Van Leggelo-Padilla/World Bank/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

It is therefore somewhat surprising that when we look at aid projects to the agricultural sector alone, we do not find that these projects are able to offset the negative impact of drought on children’s wasting. This suggests that important aid-sensitive drivers of malnutrition are found outside food production and provision systems. In addition, we cannot rule out that possible effects of these projects take longer than a year to materialize.

To conclude , our study clearly indicates that development aid strengthens recipient populations’ ability to cope with future weather anomalies. The finding that agricultural aid appears to be much less effective in the short term should not be taken to mean that funders should not prioritize these projects. Rather, we believe this particular finding speaks to the importance of cumulative and integrated efforts across aid sectors in order to strengthen local coping capacities.

The article presenting these results is downloadable for free from the journal’s web page. We acknowledge financial support from the Research Council of Norway (grant no. 250301) and the European Research Council (grant no. 648291).

Leave a Reply