The recent renewal of the mandate and the six-month extension of the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) warrants a broader discussion of its current state of affairs and future strategy. Not only has the political context of the mission changed significantly since the onset of war, but the nature of the operation has also been drastically altered. The present situation is unsustainable. With approximately 100 298 internally displaced people (IDPs) lingering in squalid improvised camps, the deteriorating security situation both within and outside the UNMISS compounds mocks its mandate to protect civilians.

The official duty of UNMISS has been revised three times since hostilities broke out in December 2013, leading to a surge in the number of personnel from 7000 to 12500. Its responsibility now includes: monitoring and reporting human rights abuses, assisting in the implementation of the January 2014 cessation of hostilities agreement, facilitating the access of civilians to humanitarian aid, and, most notably, the protection of civilians (PoC) in the midst of the armed conflict. It is the latter part of the mandate that has proven thorniest in the internecine war.

The Security Council authorised UNMISS to employ “all necessary means” to protect civilians. In fact, there is a growing pressure on UNMISS to use a pointier stick. As policymakers in the West feel compelled by domestic opinion “to do something” about the situation in South Sudan, they find it convenient to pass the buck to UNMISS.

However, UNMISS personnel have yet to open fire in the course of fulfilling their duties. This is a prudent approach. The Mission is outnumbered and ill equipped for a sustained confrontation with the various South Sudanese forces. Furthermore, in the course of the current war, UNMISS’ impartiality has constantly been questioned by both parties to the conflict. Any lethal engagement with South Sudan will result in the Mission being perceived as taking sides in the conflict and the situation may then quickly spiral out of control. Such a development would endanger its future as well as all other operations by foreign organisations in the country associated with the UN.

In an unprecedented development in the history of the UN, UNMISS has turned several Mission bases into large-scale camps for displaced civilians. During the initial weeks of the war, UNMISS had a moral obligation to open its gates and welcome people fleeing for their lives, but this should have been a temporary arrangement. UNMISS has no capacity to run what are essentially semi-permanent IDP camps.

Aside from the poor living conditions resulting from high population density combined with limited access to sanitation, protection inside these camps is also largely illusory: UNMISS has been unable to curtail a rising crime rate and the proliferating inter-IDP violence. Attacks on bases in Akobo and Bor during the first months of the conflict demonstrated that UNMISS cannot withstand determined attempts by armed groups to enter the camps. Rather than the might of the UN military contingents, it has been the wide-spread perception of UNMISS bases as “untouchable” that has ensured the safety of the IDPs elsewhere.

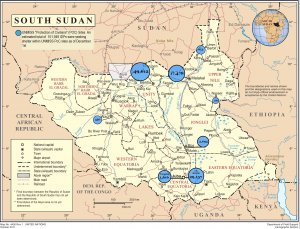

Many IDPs wish to return to their places of origin, while others would prefer to flee to a neighbouring country. In both cases IDPs need UNMISS to escort them. Most places of origin are currently regarded as war zones and are thus deemed dangerous. In Juba UNMISS has recently encouraged IDPs to return home, but many have lost confidence in the police’ ability to protect them. To the Government of South Sudan the IDP camps are an embarrassment and it insists that it is safe for the IDPs to return home. A possible solution would be for the UNMISS to escort the IDPs out of the country, but without considerable external pressure it is unlikely that the government will accept this.

While peacekeeping is based on the premise that weak states are incapable of protecting their citizens, the international community has less to offer than many believe. Its performance in the period before December 2013 is instructive. South Sudan was then ridden by local violence and regional insurgencies, but the UNMIS (and later UNMISS) – operating under more favourable circumstances than today – could do little else than facilitate the transportation of South Sudanese peace delegations and report atrocities and other news back to New York.

In today’s situation, it is folly to suggest that UNMISS can do more than before. Realistically, outside interventions like UNMISS have a limited capacity to protect civilians from war-time atrocities. But at a minimum UNMISS’ could bring the IDPs who are currently under their protection to a safer and more permanent place of refuge, and most importantly, to avoid getting embroiled in the war.

Sebabatso Manoeli, PhD student, University of Oxford and Øystein H. Rolandsen, senior researcher PRIO.

Leave a Reply