May 2014 appears to be a momentous month for South Sudanese politics. The government signed two peace agreements on 9th May in Addis Ababa, and the South Sudan Humanitarian Conference took place on 19-20th May in Oslo.

Mobilising over USD610, the Oslo conference was a response to the crisis induced by the continuing conflict in South Sudan. Although presented in the hue of a broad international conference, only half of the 41 countries present at the conference pledged new money, and a closer look at the funds pledged reveals that the Troika (USA, UK and Norway) collectively accounted for over three quarters of the money.

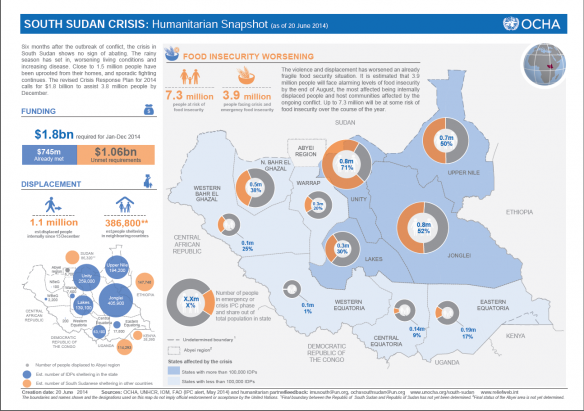

These funds are intended to alleviate humanitarian needs inside South Sudan and those of refugees in neighbouring countries. Of particular concern was a looming famine in many parts of the South. Protection of civilians was one issue deliberated during the conference, but it is unclear to what extent any of the new funds are intended to finance the planned up-scaled UNMISS operations or the IGAD-led monitoring mechanisms – both operations will cost hundreds of millions of dollars. International humanitarian assistance is however a corollary to the efforts of ending the war in South Sudan, which in this case has to be accomplished through negotiations.

On 9 May Salva Kiir and Riek Machar signed, on behalf of the Government of South Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement in Opposition (SPLMiO), an Agreement to Resolve the Crisis in South Sudan. Although the two-page agreement was described as a significant step forward in the peace process, it is by and large a reconfirmation of commitments made in earlier rounds of the IGAD-led negotiations. Furthermore, immediately afterwards, each of them claimed that he had experienced undue pressure from the Ethiopian host to sign the agreement. It appears that the for the hyped and hasty signing ceremony may have been the Oslo donor conference.

Despite some low-level fighting in the days following the signing ceremony, the two parties have generally met their commitment to a month of tranquillity. With a few days to go, it remains to be seen if the other substantial commitment – of meeting again within a month – will be honoured. The parties also agreed that an inclusive interim government is a necessary part of the solution to the crisis, but they did not decide on the composition of such a government or on when it is to be formed.

The SPLMiO has called for a new national leadership, but Salva Kiir has signalled that he is not intending to step down. The SPLMiO also demands governance reforms including the adoption of a federal constitution, a demand echoed by non-aligned Equatorian politicians. The government is apprehensive and sees federalism as a threat to national cohesion and prefers non-federal decentralisation.

The GoSS resistance to federalism is undermined, however, by the second, less-publicised, peace agreement between Salva Kiir and David Yau Yau, the leader of the South Sudan Democratic Movement/Army (Cobra Faction). It, the “Jonglei Peace Deal”, is commendable for ending four years of on-and-off insurgency in Pibor County, but it poses a threat to national integrity. It establishes the eastern part of Jonglei as an autonomous region for the Murle ethnic group and promises development funding from the central government, special rights to manage water and pasture resources, and concessions over internal borders. The new arrangements bypass the current governance structure in Jonglei and might encourage other disgruntled groups to intensify their activities. It is still too early to say whether this is the start of South Sudan’s fragmentation, but the stage is set for an upsurge of ethnic and regional demands.

The weakness of the May 9 agreements is to a large extent the consequence of the haste with which they were made. This is symptomatic of the dilemmas facing external actors involved in peace processes in the two Sudans. There are good reasons for accelerated processes: protracted warfare not only takes an unacceptable toll in terms of human lives and destroyed livelihoods, but it also undermines South Sudan as a political project. However, as the catastrophic outcome of the 2006 Darfur peace agreement illustrates, forcing through premature solutions in South Sudan may be devastating in the long run.

Øystein H. Rolandsen, senior researcher PRIO, and Sebabatso Manoeli, DPhil student, St. Antony’s College, Oxford University.

Post-Script

Since we published this analysis, the month of tranquility ceased sharply on 31 May as fighting reignited between SPLMiO and the GoSS troops. The recent events corroborate the argument that the external pressure exerted on the two signatories could not circumvent the essential ingredient for peace: political will, on both sides. The continuing conflict indicates that the two parties did not have a sense of ownership over the agreement, and that signing on 9 May may have been premature. The UN’s insistence on holding those who transgress the agreement accountable leads to questions about the kind of justice that can and will be meted out.