Perceptions of peace negotiations tend to shift rapidly from inertia to optimism, to disillusion and back to inertia. Peace talks also tend to be long-winding. True to form, the IGAD (Intergovernmental Authority on Development) facilitated negotiations between the Government of South Sudan and its opposition led by Riek Machar has been a roller coaster ride – and it has barely begun. In early January we saw endless discussions over format and agenda, then, on 23 January the parties signed an agreement on cessation of hostilities and agreed on the initiation of a political process to address current challenges (see brief 1 for a more detailed analysis). If not a genuine breakthrough, the agreements nevertheless indicated a willingness to talk.

The agreements did not provision a release of the politicians detained in Juba, but it appears that some kind of reciprocity was expected after the Opposition agreed to cessation of hostilities. Seven of the eleven detainees were subsequently released “on bail” to Nairobi where the Kenyan government initially denied them permission to leave Kenya. However, international political pressure was brought to bear and Riek Machar responded by announcing that unless the former detainees were allowed to attend, he would boycott the negotiations. Eventually they were allowed to travel to Addis to attend the peace talks to which they became a third party, or “block”, naming themselves SPLM leaders former detainees.

Apparently this third block still agrees with Machar’s criticism of the current state of affairs in South Sudan and has similar demands for political reform, but they do not condone Riek Machar’s armed rebellion. It might very well be that this group of politicians indeed does not regard political violence to be the right means at the moment, but there are also other reasons why they have not joined Machar. Perhaps most important, they do not want to become subordinate to Machar. Their earlier political alliance on display at the press conference 6 December 2013 was tactical and only reflected agreement on the demand for Salva Kiir to step down. Who the members of the third block want as his successor is not clear, but it is certainly not Riek Machar.

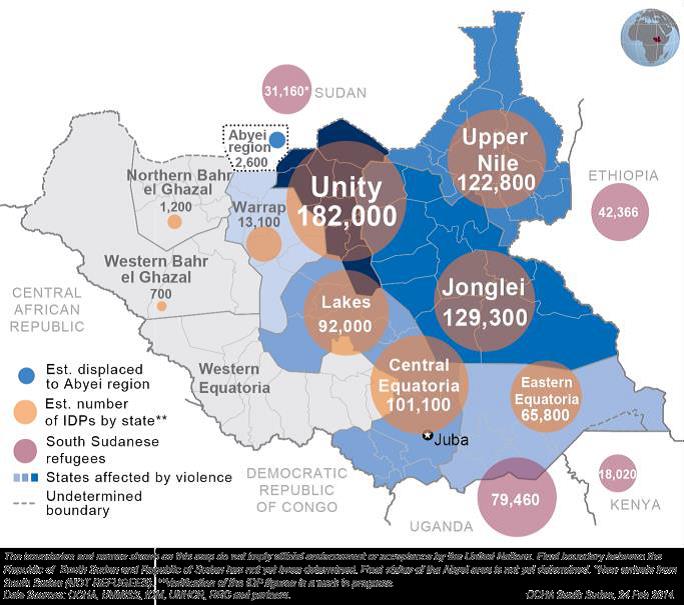

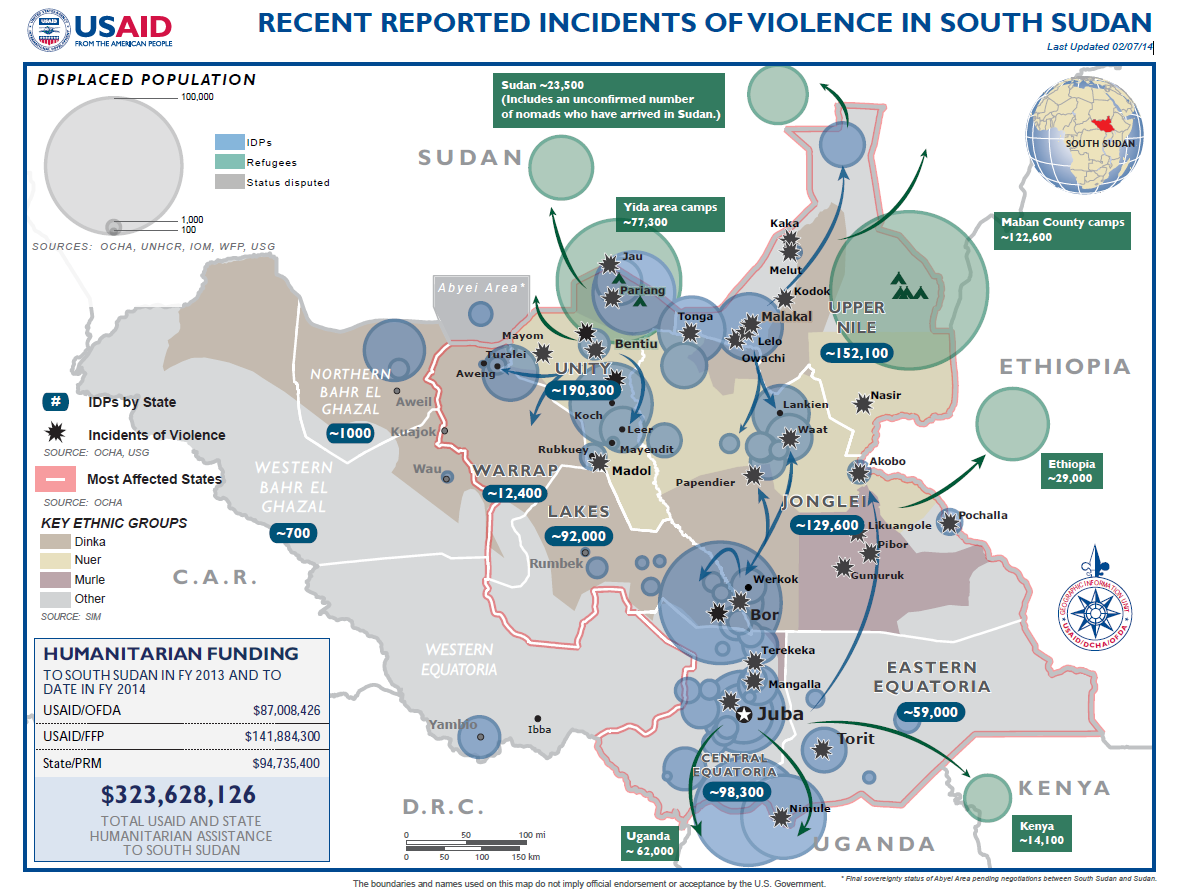

Recent developments – notably the attack on Malakal over the weekend – confirm that Riek Machar and his SPLM in Opposition has the capacity to destabilise and harass Government forces in Greater Upper Nile and at the very least to disrupt some of South Sudan’s strategically important oil production. But, the Opposition seems to lack the military strength and co-ordination needed to control larger towns. Moreover, it appears that African states and other strategic allies, as well as the UN, are willing to invest considerably in avoiding a capture of Juba and a subsequent military seizing of power by the Opposition. It is too early to conclude that this is a stalemate, but the situation does not suggest that a military resolution of the crisis is imminent. Unfortunately, there are no signs that any kind of durable political compromise is in the offing either.

It is still not clear what kind of political process the IGAD talks in Addis is supposed to initiate. The immediate problem is the leadership crisis within the state bearing party, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement. But underneath there is a dual challenge that needs to be addressed:

Firstly, the SPLM is a grand coalition of some of the major political forces within South Sudan and a break-up of the party has been expected. Lam Akol already left the movement and established the SPLM Democratic Change prior to the last election in 2010. The faith of SPLM DC illustrates one of the challenges with being an opposition party in South Sudan: lack of resources. Aspiring opposition party leaders have to either be independently wealthy or find a secret (foreign) sponsor to be able to run a political party and an election campaign. Although officially and formally independent from the Government of South Sudan, the SPLM has the whole government apparatus to draw upon in the next election. Under the current arrangement, whoever controls the SPLM will win the Presidential election. Or, put differently, whoever controls the government, also controls the SPLM. Therefore, the cost of forming an opposition party is prohibitively high and the only viable path to power is within the SPLM.

Secondly, there are many disenfranchised elites and intellectuals in South Sudan which are not part of the current process. The locus of power within the SPLM is with the initial nucleus of intellectuals who turned fighters in the mid-1980s. This excludes those that joined the movement at a later stage, notably many in the three Equatoria states to the South, but also refugees who returned after peace in 2005, women (despite the introduction of nominal 25 % women quota) and a rapidly expanding “youth” segment. In consequence, even in the unlikely event that the SPLM leaders negotiating in Addis should reach a compromise acceptable between themselves they will increasingly be challenged by these excluded elites. The citizens’ initiative calling for direct participation of civil society in the peace talks might be seen as the most articulate and non-partisan group hailing from these “outsiders”.

Summed up, the crisis in South Sudan is destined to last since we still do not know:

- what kind of process is needed to solve the crisis in South Sudan;

- what kind of compromises will be possible to reach; and,

- who among the South Sudanese are going to participate in this process.

Anyone suggesting that this cluster of problems will be solved in the near future is betting against high odds.

Øystein H. Rolandsen, Senior Researcher PRIO and Helene Molteberg Glomnes, Research Assistant, PRIO