Yesterday, The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) announced that it will employ a joint East African Protection and Deterrent Force (PDF) as a part of the agreement of cessation of hostilities in South Sudan (see previous blog post). According to the announcement, Ethiopia, Kenya, Burundi and Rwanda, possibly also Djibouti will contribute troops to the force, which is supposed to be operational by mid-April. This development accentuates two underlying issues related to IGAD’s role a as a peace facilitator in the South Sudan conflict: its capacity and neutrality.

IGAD is an institution consisting of eight member countries and has first and foremost been involved in diplomatic efforts to secure peace in Sudan and Somalia. It has a relatively weak mandate and none of the member countries have shown any interest in developing IGAD into a fully functional multilateral organisation. It continues to be dependent on donations from Western countries, often on an ad hoc basis. In the case of Sudan and South Sudan peace processes financial and technical support is provided by, among others, the “troika countries” (USA, UK and Norway). Now, for the deployment of the new IGAD force, both the AU and the UN Security Council has been asked to provide technical and logistical support, in other words, to bankroll the operation. AU has little or no resources to contribute and it will be the Western countries that will carry the financial burden of this operation. This means that the IGAD’s capacity to host negotiations and maintain a protection force is to a certain extent at the discretion of others. For IGAD as an institution this kind of dependency on external actors might endanger its ability to be a political instrument for its member countries.

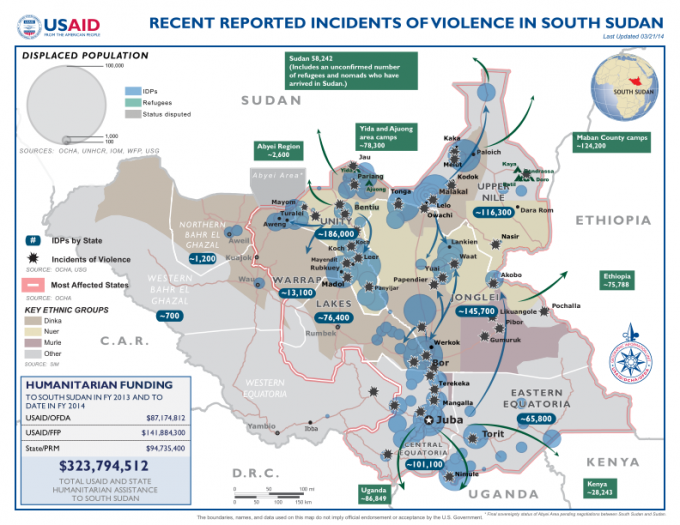

Also the IGAD countries’ proximity to South Sudan and involvement in the conflict outside of the negotiation room threatens to compromise its legitimacy as a neutral facilitator. It is noticeable that Uganda has not been mentioned as one of the contributing countries to the PDF. Uganda’s neutrality has been questioned due to the involvement of its troops in the conflict. On the request of the South Sudan government and tacitly approved by IGAD, Ugandan forces were deployed to assist the South Sudanese government in protecting infrastructure and prevent escalation of the conflict. But, there is little doubt that these forces also actively participated on the Government side in campaigns against the SPLM/A in Opposition led by Riek Machar. The latter has even accuses Ugandan troops of using cluster bombs in their attacks on Opposition forces in Jonglei. Whether the latest accusations hold true or not, the military involvement on one side of the conflict has undermined Uganda’s credibility as peace facilitator. Following pressure from the international community, including the UN and IGAD, Uganda has agreed to remove its troops from South Sudan. But only when a replacement force is in place, which assumedly will be the PDF.

It is noticeable that also Sudan, the former enemy and neighbour to the north, is not part of the planned Protection and Deterrent Force. The possibility of Sudan protecting oil assets in South Sudan has been on the agenda in talks between representatives of two countries, but nothing has materialised so far. Sudan competes with Uganda to gain influence in the new nation and also has interests in a certain level of stability to ensure that oil production is not interrupted. But, it appears that Sudan is not regarded as sufficiently neutral to contribute to the PDF.

Sudan is also a member of the Arab League, another international body signalling interest in assisting in solving the conflict: For the first time, South Sudan foreign affairs minister, Barnaba Marial Benjamin, is invited to an Arab League meeting of foreign ministers. He sees the League as an arena that may contribute to a peaceful solution in South Sudan. The Arab League has not yet invited the opposition and it will probably be difficult to contribute constructively unless they involve more than one party to the conflict.

The IGAD countries have a deep vested interest in avoiding a full implosion in South Sudan. None of the neighbours would like to have an insecure, non-governed territory along their border. Also, more than 171,000 refugees have already fled South Sudan to the neighbouring countries. Finally, South Sudan is economically important to Kenya, Sudan, Ugandan, Ethiopia, Eritrea; even people from Somalia made good money in South Sudan before the conflict started in December last year. The regional dynamics impact the IGAD countries’ role as peace facilitators, but it also make them best positioned to convince the warring parties to end the conflict. Even with its limited capacity, IGAD is the organisation best suited to facilitate the peace process.

Øystein H. Rolandsen, Senior Researcher PRIO and Helene Molteberg Glomnes, Research Assistant, PRIO