By Olaf Corry

What security problems are likely to be involved in developing and using technology to deliberately modify the global climate ?

Some argue that effective global action to prevent global warming is too difficult politically, and that ‘dimming the sun’ should be explored. The idea is that a possible way to reduce climate risks is by limiting the amount of solar radiation that actually reaches the earth. One model involves continuously spraying aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect more light back out into space, and in the process lowering global temperatures. Rather than being seen as a replacement for efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such ideas have been presented as a ‘Plan B’ that should be considered to allow extra time for greenhouse gases to be dealt with.

However, there are risks involved in using such high-leverage geoengineering technologies. My article, recently published in Security Dialogue, argues that the ability of geoengineering to reduce climate risks depends, ultimately, not just on technological innovations and avoiding ‘moral hazard’ but, rather, also depends on avoiding the potential for a new type of ‘security hazard’ to emerge.

Well-ordered global politics must therefore be a key component in any such ‘Plan B’ to cool the Earth… any imagined future comprehensive framework for cooperation on geoengineering rests on some fairly optimistic assumptions about the rationality and temperateness of leaders, and on the effectiveness of global governance in general.

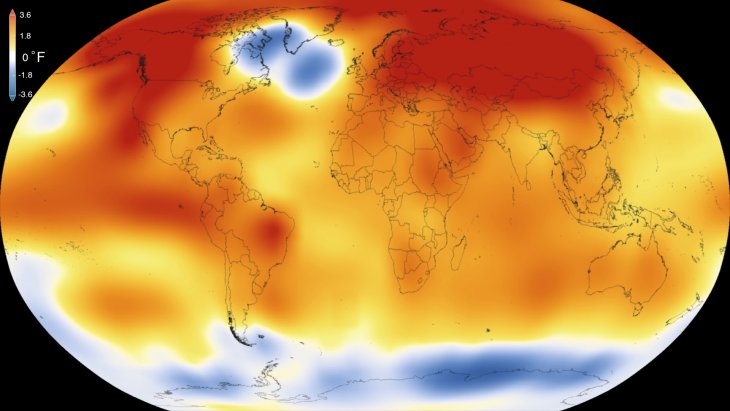

Global Temperatures in 2015- NASA- Public Domain under Wikimedia Commons. https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/thumbnails/image/16-008.jpeg

First, even if no major unexpected effects ensue, diverging interests and risk profiles would make the use (or non-use) of geoengineering intensely political. Even keen supporters of stratospheric aerosol injection warn strongly against deployment without adequate global agreements, accountability and oversight. ‘Rogue’ or inadequately governed climate engineering outside a comprehensive agreement could exacerbate threats to international peace and stability. Well-ordered global politics must therefore be a key component in any such ‘Plan B’ to cool the Earth. Although theoretically cheaper than decarbonizing the global economy, any imagined future comprehensive framework for cooperation on geoengineering rests on some fairly optimistic assumptions about the rationality and temperateness of leaders, and on the effectiveness of global governance in general. Incentives to cooperate exist but so do incentives to go it alone, to override objections, to deny compensation to ‘losers’, to geoengineer in somebody’s interests more than others’, or to abuse the technology in other ways.

Moreover, by making the global weather something somebody ‘does’ to somebody else, high-leverage geoengineering potentially risks introducing friend-enemy dynamics into climate politics as a whole. Not only might this make geoengineering effectively unavailable as a Plan B, but by making climate politics part of existing geopolitical rivalries and security dynamics it also risks making Plan A (greenhouse gas emissions reduction) even more difficult to achieve. ‘Security’ is a special category of politics in which so-called ‘normal’ rules and methods are often set aside in favour of exceptional ones due to existential threats, real or otherwise. Such ‘exceptional’ measures could and usually do include violence, secrecy, and a variety of undemocratic measures justified for ‘security reasons’. States deploying geoengineering may, via the climate, appear as existential threats to others. Even ‘random’ weather events could become geopolitically contentious.

Research and further exploration of these technologies should not be ruled out, but the ‘security hazard’ associated with geoengineering should be taken seriously when assessing whether or not new technologies are likely, ultimately, to reduce or exacerbate risks associated with climate change.