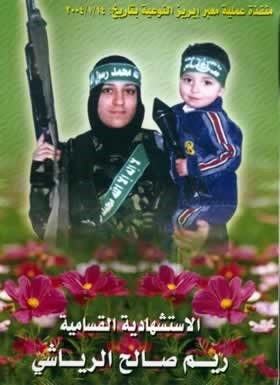

In Hamas’ 2004 poster of suicide bomber Reem al-Riyashi, she poses for the camera holding a rifle her in left hand and her son in the other. al-Riyashi killed four Israelis and herself in a joint Hamas and al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades bombing on the Gaza-Israel border.

The Savior of the Erez Crossing Operation executed on January 14, 2004 Al-Qassam Martyr Reem Salem AlRiyashi,” Hamas, 2004; Filasteen al-Muslimah

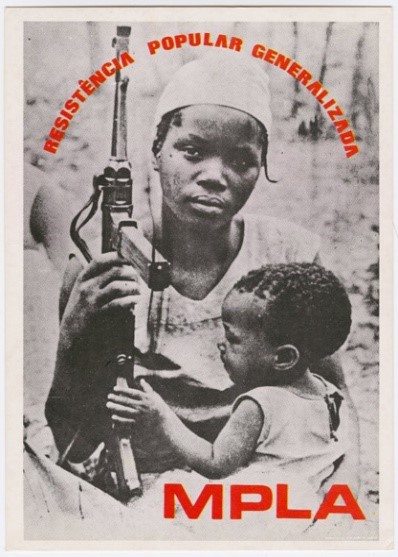

Over twenty years earlier, and nearly 5,000 miles away, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) produced a similar poster featuring a nearly identically positioned militant with her gun and child. These are markedly different organizations, and the former rarely includes women on the front lines. But these groups employed the same ‘armed mother’ imagery in their visual messaging, as part of a cross-national trend. In my recent Security Dialogue article, I explore why and how militant organizations across conflicts use this imagery to contextualize, justify, and humanize political violence.

“Widespread Popular Resistance, MPLA,” MPLA, 1970s; Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Women’s participation can be fruitful for militant groups. Because women are assumed to be non-violent and peripheral to conflict, their participation can humanize rebellion. For example, in Nepal Maoists “mobilized women to give the message that the armed conflict was a demand on all people; such a noble war that even women would fight, supporting and sympathizing with it” (Dahal 2015: 188). In El Salvador, some families reported being more comfortable letting their children join the FMLN when approached by female recruiters because they viewed women as less threatening and more trustworthy (Viterna 2013).

But generally, women’s armed involvement still violates social and political gender expectations. Militant groups risk backlash from community members, and even comparatively egalitarian organizations frame women’s involvement as evidence that the state destroyed social order (c.f. Viterna 2013). I conclude that ‘armed mother’ imagery is a tool for reconciling these complex dynamics in militant publicity. By leveraging life-giving as the ‘natural’ role for women, these images signal violent disruption of everyday life and authorize political violence in response. But they also stress the temporariness of gender role expansion, promising and preserving a ‘return to normal.’ Armed mothers therefore contextualize women’s violence and use those narratives to legitimize rebellion. While we do not know how well these narratives work in shaping people’s views on militancy, this approach is so popular that some groups use ‘stock images’ of armed mothers from other conflicts in their own outreach, and ‘armed mothers’ even appear in posters from groups who exclude women from front line participation.

In my Security Dialogue article, I demonstrate this visual practice using 16 ‘armed mother’ posters from six diverse conflicts. This research offers a window into militants’ publicity campaigns. It illuminates how politically violent groups perceive and explain women’s participation and emphasizes the role gender plays in organizational dynamics. Moreover, this work highlights the importance of visual scholarship and its practical implications for understanding the contextualization and legitimation of political violence.

Works Cited

Dahal S (2015) Challenging the Boundaries: The Narratives of the Female Ex Combatants in Nepal. In Shekhawat S (ed). Challenging Gender in Violence and Post-Conflict Reintegration, Palgrave MacMillan

Viterna J (2013) Women in War: The Micro-Processes of Mobilization in El Salvador. London: Oxford University Press