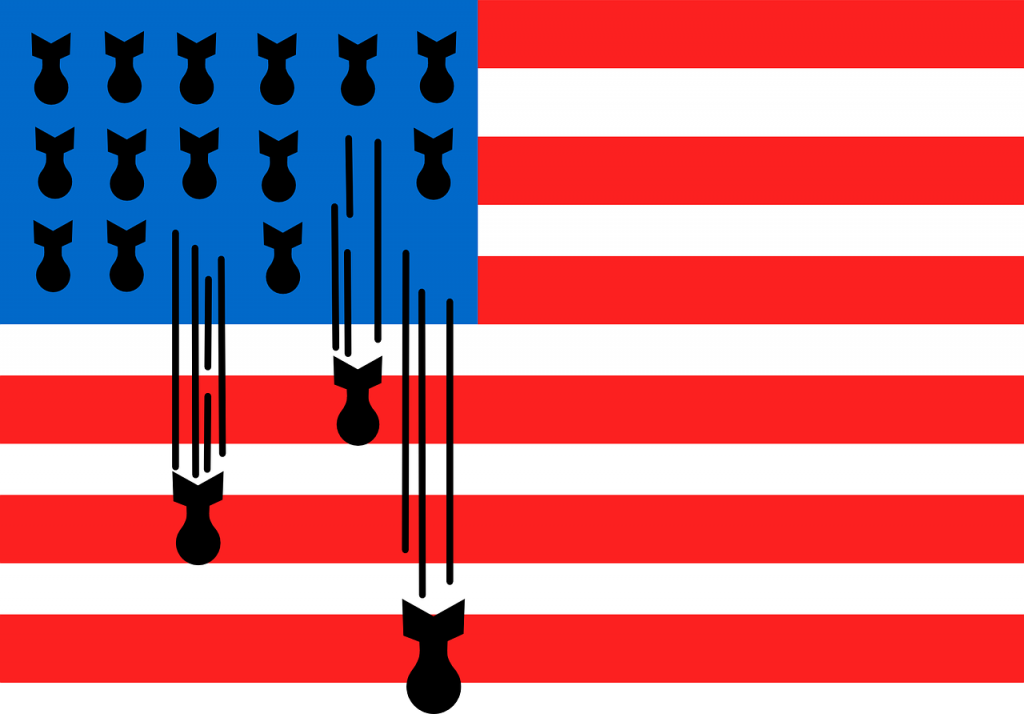

In this research project, I explored how the United States (U.S.) has redefined the concept of ‘imminent threat’ to relax the rules for anticipatory use of armed force against insurgent groups. In particular, two new definitions of imminent threat have changed the conduct of specific combat activities: drone strikes and ground combat operations.

In the first part of the article, I examined how the Obama administration redefined, in late 2011, the concept of imminent threat in jus ad bellum in order to establish the legal basis for targeted killings of individuals suspected of being senior leaders of Al Qaeda and affiliated groups. My objective was to show how the Obama administration changed the definition of imminent threat by eliminating two of its key traditional components – that is, the immediacy and certainty of the threat. The new – “flexible” and “broad” – definition of imminent threat enabled the U.S. military to start launching anticipatory attacks with unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones, against vaguely defined threats. By describing imminent threats as continuous threats that were present at any time because terrorists supposedly continuously planned attacks against the U.S., the new definition of imminent threat significantly broadened the temporal limits within which the U.S. military was permitted to conduct military operations, including drone strikes. The U.S. military was permitted to launch continuous armed attacks against presumed continuous imminent threats without having to collect evidence showing when and where such threats were about to emerge. Moreover, the new definition of imminent threat also widened the geographical scope of anticipatory “self-defense” operations. Given that members of Al Qaeda and associated forces operated in dozens of countries around the world, the new concept of imminent threat enabled the U.S. military to launch military operations in all of those countries. Under the new doctrine, it became irrelevant whether the countries in which members of Al Qaeda and their affiliated forces were hiding were at war with the U.S.

”[T]he redefinition of imminent threat in ground combat operations led to an increase in violence against civilians”

In the second part of the research, I examined how the Bush administration redefined the concept of imminent threat in ground combat operations in 2005. The redefined concept was unveiled in the U.S. Rules of Engagement, thedirectives delineating the circumstances and limitations under which U.S. troops are allowed to use force against enemy troops. Crucially, both the Bush and Obama administrations embraced a redefinition of imminent threat that abandoned one of its key traditional elements – that is, the immediacy of the threat. The new definition was used to relax the rules for anticipatory self-defense in ground combat operations, in particular in kill-or-capture missions or night raids. The expanded notion of imminence enabled U.S. troops to categorize as an imminent threat a range of movements and actions that did not represent an immediate threat but merely indicated that a threat might emerge at some unspecified moment in the future. For example, such movements and actions included: using a mobile phone in the vicinity of U.S. troops; digging a hole, particularly at night, in the vicinity of a road; stepping out of a house during a night raid; fleeing from the scene of a night raid; possessing a weapon. With such broad threat categorizations, the line dividing civilians and legitimate military targets became blurred, which increased the risk for civilians getting killed or injured.

New definitions of imminent threat prevented the application of the principles of necessity and proportionality during the pre-emptive use of force against perceived imminent threats. In order to show how the U.S. military failed to observe both principles in drone strikes, I focused on the principles of necessity and proportionality incorporated in jus ad bellum, the norms regulating the use of armed force in international relations. In addition, I examined the principles of necessity and proportionality in jus in bello, the norms governing the conduct of hostilities in armed conflicts, in order to explain how the U.S. military ignored both principles in ground combat operations.

One of the key findings of the research is that the redefinition of imminent threat in ground combat operations led to an increase in violence against civilians. The too-broad definition of imminent threat enabled U.S. troops to be more flexible in deciding when to pull the trigger in “self-defense” engagements, which led to civilians being more often put in danger of getting killed or injured. While it is true that imminent threat determinations were always, to a certain extent, subjective, the new concept of imminent threat allowed excessive subjectivity that significantly undermined civilian protection.