Edited by Linnet Taylor, Gargi Sharma, Aaron Martin & Shazade Jameson. Meatspace press. 306p

Data Justice and COVID-19 questions how the widespread deployment of digital technologies to fight COVID-19 has affected data governance and data justice. Written in ‘real-time’ during the first wave of the pandemic, the volume brings together 38 essays – comprising 28 “dispatches” from individual countries or regions and 10 commentaries problematizing the dispatches. Contributions stem from scholarship on data justice, defined in earlier work from Linnet Taylor (2017) as examining “fairness in the way people are made visible, represented and treated as a result of their production of digital data.”

”[T]he book’s main strength is to provide …useful pointers for future analytical research that go beyond data justice scholarship – and make this book relevant to a wider audience… .”

The geographic diversity and topical breadth of the contributions provide a valuable snapshot of the deployment of digital technologies during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic. But the book’s main strength is to provide at least three useful pointers for future analytical research that go beyond data justice scholarship – and make this book relevant to a wider audience, including the general public and scholars working in the fields of critical security studies, information technology, humanitarian studies and global health. First, it documents the expansion of state surveillance in the name of public health, or what the editors call ‘the epidemiological turn in digital surveillance’. Second, it problematizes the hype around technological fixes or ‘techno-solutionism’ by exploring its consequences for inequalities and social justice. Third – and this might be the book’s most original contribution – it questions the entanglement of state and corporate power by unpacking the cooperation between public and private-sector actors that makes the deployment of digital technologies possible.

The ‘epidemiological turn’ in digital surveillance

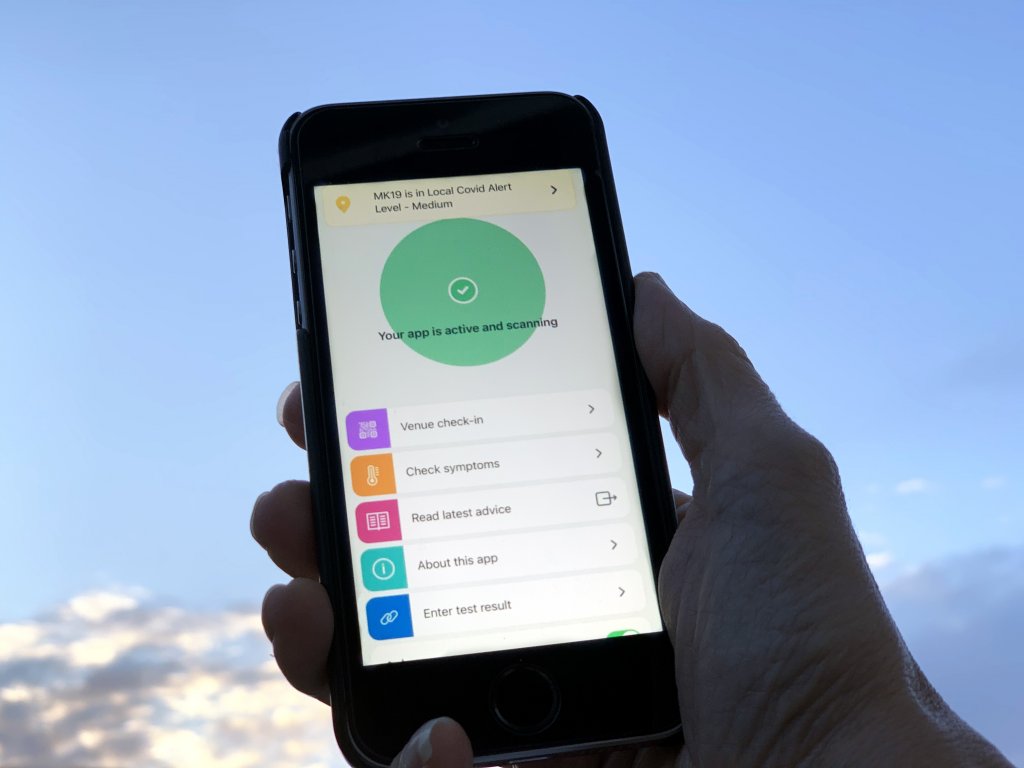

The volume offers a damning account of how governments around the world have taken advantage of the pandemic to expand digital surveillance of citizens without appropriate legal basis and adequate democratic oversight. Accounts from Argentina (Ugarte), China (Wang), Hungary (Böröcz), Mexico (Cruz-Santiago), The Philippines (Lucero) and Poland (Brewczyńska) all raise deep concerns about the potential misuse of digital surveillance technologies such as contact tracing apps for repression and human right violations within a wider context of (rising) authoritarianism and/or a track-record of state-power abuses. Even more troubling, the dispatches reveal similarly hasty and legally dubious deployment of surveillance technology in democratic societies such as Norway, where the government ultimately abandoned its pilot contact-tracing app after much public debate and an enquiry from the data protection authority (Sandvik).

Whereas security and the fight against terrorism have traditionally been invoked to justify digital surveillance, the COVID-19 pandemic – the editors argue – provides a radically new set of justifications to legitimize and expand digital surveillance in the name of public health. This ‘epidemiological turn’ in digital surveillance could have deep and long-lasting effects on democratic and authoritarian societies alike that will undoubtedly be analyzed by critical security studies in the years to come.

‘Techno-solutionism’ and inequalities

Many contributors problematized the hype surrounding the digital technologies deployed to fight COVID-19 pandemic as ‘techno-solutionism’ (Marda; Arroyo & Luján; Appelman, Toh, Fathaigh & van Hoboken; Cohen) or what Sean McDonald calls ‘techno-theatre’, which is a way for politicians and companies to focus “public attention on elaborate, ineffective procedures to mask the absence of a solution to a complex problem” (McDonald, p23).

Glossy tech solutions distract us not only from the deficiencies that have led to inadequate pandemic responses in the first place, such as broken public systems, lack of trust, or social inequalities: the overwhelming focus on their hyped-up potential also conceals their limitations (Marda). Several of the commentaries (Marda; Edwards; Yeung; Keyes; Daly; Sharbain & Anonymous II) warn that digital solutions will inevitably reinforce inequalities by excluding vulnerable groups; those excluded from the digital world due to poverty, techno-illiteracy, or other reasons. Moreover, many of these digital solutions, such as contact tracing apps, are being used experimentally, without evidence of their efficiency, nor appropriate reckoning of their inherent trade-offs – including private companies’ long-term commercial interests.

Public-private cooperation for the deployment of digital technologies

For me, this volume’s most exciting contribution is to direct attention to the interaction and cooperation between public authorities and private tech companies during the pandemic. Big Tech companies like Google, Apple and Facebook, which already wielded unprecedented power pre-Covid, have seized the opportunity offered by the crisis to considerably strengthen their positions and advance their interests – what Naomi Klein coined ‘disaster capitalism’.

Big Tech’s contribution to the fight against COVID-19 has often been framed in terms of social corporate responsibility, undertaken pro-bono in the name of social good. Google-Apple developed for instance a common exposure notification system to use free of charge in contact tracing (Veale; Appelman, Toh, Fathaigh & van Hoboken); Amazon pledged to make no profit in its contract with the Canadian government to supply medical equipment (Wylie); and Facebook helped the Australian government develop a chat bot on its platform WhatsApp to facilitate public health communication (Johns).

”The editors have impressively, and in record time, gathered a diverse group of scholars, and they have succeeded in setting out a promising research agenda.”

Such initiatives, contributors note, provide an efficient PR campaign and useful “reputation laundering” for companies accused of exploiting their employees (Amazon); spreading fake news (Facebook); abusing their market position and extracting and commodifying our data (Google, Apple, Facebook & Amazon). Moreover, many of the authors also note that Big Tech is consolidating and expanding its market power, making important moves towards the highly promising and profitable healthcare market. The digital solutions offered during the current crisis may also potentially create new needs and forms of dependency for the state; as illustrated by the contact-tracing app developed pro-bono by a consortium of public-private entities in France, but carrying relatively high maintenance costs (Musiani). Finally, the entanglement of state and private interests raises questions about the secrecy surrounding their involvement. Several of the dispatches document a worrying lack of accountability and transparency in the contracts awarded to tech companies.

What about ‘the digital turn’ in public health?

The book explicitly stems from scholarship on ‘data governance’ and ‘data justice’. The editors have impressively, and in record time, gathered a diverse group of scholars, and they have succeeded in setting out a promising research agenda. At the same time, the book would have benefitted from engaging with scholars working not only on the governance of data, but also on the governance and politics of global health.

The volume does not address, for instance, how digital solutions may originate in and be integrated into the public healthresponses to the pandemic. It remains unclear how the widely discussed issue of digital contact tracing differs from ‘traditional’ contact tracing; and how what we may call a ‘digital turn in public health’ will affect the public health response. While the volume interrogates how public health may legitimize the digital surveillance of citizens, it fails to acknowledge that population and disease surveillance is precisely a key function of public health and a necessary tool to prevent, prepare for and respond to pandemics. Similarly, the book does not contextualize the use of digital technologies in earlier disease control efforts and pandemic preparedness initiatives; nor does it unpack the politics underpinning the deployment of digital technologies within global health security (see for instance: Roberts and Elbe 2017; Bengtsson, Borg, and Rhinard 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic offers a unique opportunity to start interdisciplinary dialogue across various scholarships, including data governance, critical security studies and global health politics. Scrutinizing the coming together and cooperation of the public and private sector in the deployment of digital technologies in the health sector offers one promising avenue to do so, as we also have found through our projects and conference organized by the Independent Panel on Global Governance for Health at the University of Oslo.

References

Bengtsson L, Borg S and Rhinard M (2019) Assembling European health security: Epidemic intelligence and the hunt for cross-border health threats. Security Dialogue 50 (2): 115-130.

Roberts SL and Elbe S (2017) Catching the flu: Syndromic surveillance, algorithmic governmentality and global health security. Security Dialogue 48 (1): 46-62.

Antoine de Bengy Puyvallée is a PhD Fellow, University of Oslo’s Centre for Development and the Environment.