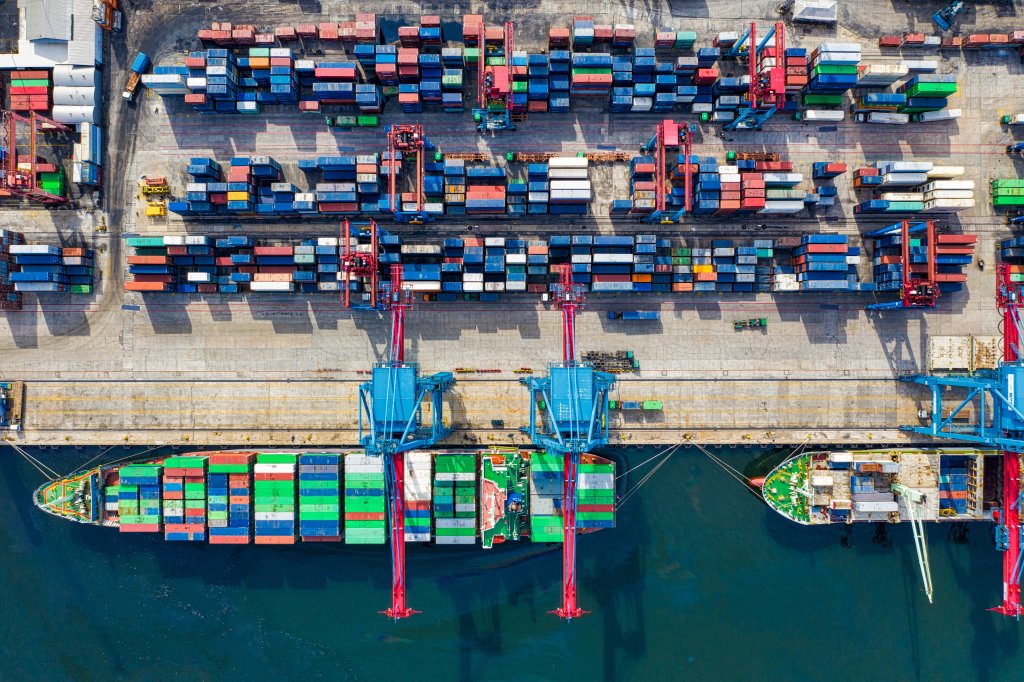

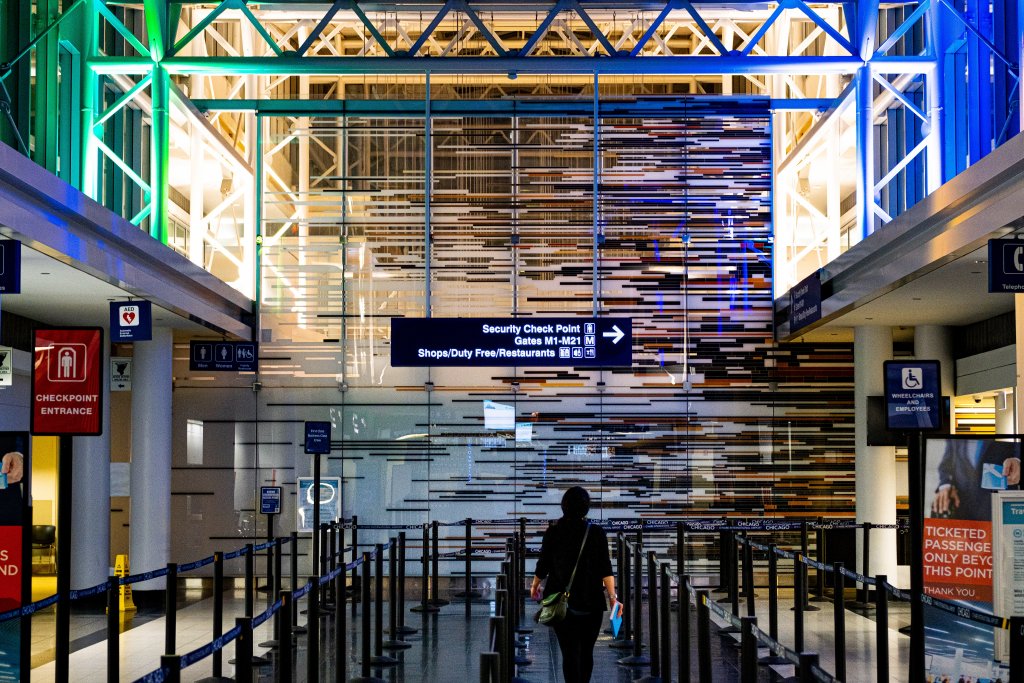

Global transportation hubs such as airports and maritime ports have become vital spaces for the international networked economy. Global economic opportunities depend on the effective flow of people and things, and make use of the different infrastructures and modes of the transport system. For instance, around 80 percent of global trade in goods, measured by volume, is carried by sea. Similarly, since the 1970s, when air travel ceased to be the preserve of elites and became available to the masses, aviation has seen tremendous growth and now acts as significant catalysts for socio-economic development. In this sense, airports and ports are prominent hubs, and are instrumental in connecting local and national regions to international ones.

However, the fact that global hubs are considered critical infrastructures serving as symbolic locations of contemporary capitalism, commerce, and mobility, does not come without its risks and vulnerabilities. Although illicit activities and criminal exploitation (such as smuggling, piracy, and theft) have long been associated with the aviation and maritime industries, new and emerging risks have been added to a broadened security agenda. In particular, given the numerous terror attacks there have been, most notably 9/11, the London bombings in 2005, and the 2016 Brussels bombings, which targeted various parts of global transportation hubs (such as airlines, railways, and metros), concern about terrorism is very much to the fore in the imaginaries of airport and maritime port life. Therefore, in today’s environment, the security discourse of terrorism stands strong.

Influenced by the ‘war on terror’ discourse, the security landscape of airports and ports seems to be operating under constant threat of an exceptional nature with a minimal margin for error, because the potential consequences are so significant. Following the perceived necessity to make global hubs safe, numerous measures have been implemented, including stringent regulatory regimes and different tools for surveillance, controls, and risk management. Consequently, the heightened (in)security and exceptional threats influence the everyday environment of the aviation and maritime sectors, in that they are affected by embodied emotional responses, such as uncertainty, fear and anxiety, felt by passengers, customers, and employees.

In my recent article in Security Dialogue, I engage with the debates on exceptionality and the everyday by unpacking how security agencies at global transportation hubs experience and cope with exceptionality in their everyday working life, and I examine how they feel about it, interpret it and respond to it. In doing so, I present arguments for moving attention from ‘spectacular’ and ‘exceptional’ events to the mundane, everyday nature of security in order to add a new layer to our understanding of security projects.

The empirical assessment documents the impact of the exceptional through the embodied experiences of living with seemingly constant risk and uncertainty. In response, security agencies actively seek to compensate for the uneasiness in their everyday life by relying on instrumental governing logics, with risk management and analysis used to render uncertainties manageable and tangible. The use of these logics and measures are understood as prominent aspects of the coping strategies as developed by the agencies. As I demonstrate in my article, however, another way of coping with exceptionality in their everyday working life also emerged amongst the security agencies, one in which emphasizes the human dimension of security practices. This means that the value of human qualities is recognized when confronting the consequences of exceptionality in the security landscape of airports and ports. In particular, I illustrate how the notion of everyday security consciousness figures in the life of security agencies. Closely associated with this is the emergence of mechanisms of resistance that provide excitement and alleviate boredom, in response to what is sometimes seen as an overemphasis on the importance of the tangible nature of security practices. As part of their emotional response those delivering security find ways, in the way they perform security, to ridicule and challenge its instrumental governing logic.

Therefore, I suggest that, as emotions play an important role in how we experience and respond to security measures, it is crucial to pay attention to the embodied emotional experience and everyday security consciousness. Future attention to the role of emotions in experiences of security may offer crucial insights into the micro-practices or micro-politics of (in)security.

The future is (or ‘futures’ are) ‘modular’ & ‘mobile’ so that will indeed need to be faciliated as much and as far as possible via such mechanisms – see, for example, ‘standardisation’ processes.