Monday 18 August

- The UN demanded freedom of movement in South Sudan.

- The South Sudanese government accused the SPLA-in-Opposition of seeking support from Sudan.

- An SPLM-in-Opposition delegation arrived in Kampala to meet the Ugandan government.

- Seven people were killed in Lakes State.

Tuesday 19 August

- The radio journalist detained in Juba last week was released.

- The South Sudanese government warned that it will withdraw from the peace talks unless cessation of hostilities is agreed upon.

- The SPLM-in-Opposition accused the South Sudanese government of boycotting the peace negotiations.

- The South Sudanese Presidency opposed the suggestion to create a prime minister position.

- Salva Kiir dismissed several justice ministry lawyers.

Wednesday 20 August

- The mediators representing the South Sudanese government withdrew from the IGAD peace talks.

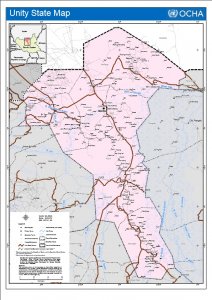

- Human Rights Watch reported that the SPLA used child soldiers in recent fighting in Bentiu.

- South Sudan stepped up its measures to prevent Ebola spreading to South Sudan.

- China’s foreign minister put pressure on South Sudan.

- Human Rights Watch demanded that China stops selling weapons to South Sudan.

- The Council of States discussed the creation of ten new counties in South Sudan.

- Salva Kiir dismissed Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior, widow of the late John Garang.

- The SPLM-in-Opposition held a closed-door meeting with the Ugandan government.

- The Twic East Commissioner announced that more than 900 families from Twic East have fled their homes due to floods.

- The South Sudanese government claimed to have captured thirteen SPLA-in-Opposition soldiers in Bentiu.

Thursday 21 August

- Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) described the situation in the UN camps in South Sudan as inhumane.

- US Congress leader Edward Royce demanded arms embargo on South Sudan.

- South Sudanese civil society demanded that the warring parties resume the peace talks.

- The SPLA denied having recruited child soldiers.

Friday 22 August

- The SPLA-in-Opposition accepted the presence of Ugandan troops in South Sudan.

- Political parties participating in the IGAD peace talks announced that Lam Akol is no longer their leader.

- The SPLA claimed it has revealed that the opposition is planning a major offensive.

Saturday 23 August

- AU reiterated its call for sanctions against South Sudan’s leaders.

- Citizens gathered for peace in Rumbek (Lakes State).

Sunday 24 August

- An IGAD ceasefire monitor died of a heart attack after being held by the SPLA-in-Opposition.

- IGAD postponed the resumption of the peace talks until Monday 25 August.

- The SPLA-in-Opposition accused IGAD ceasefire monitors of assisting government spies.

- Two government soldiers were killed in a shoot-out in Bahr el Ghazal.

- The SPLA claimed that SPLA-in-Opposition soldiers entered Unity State from Sudan.