*An in-depth review from @SecDialogue

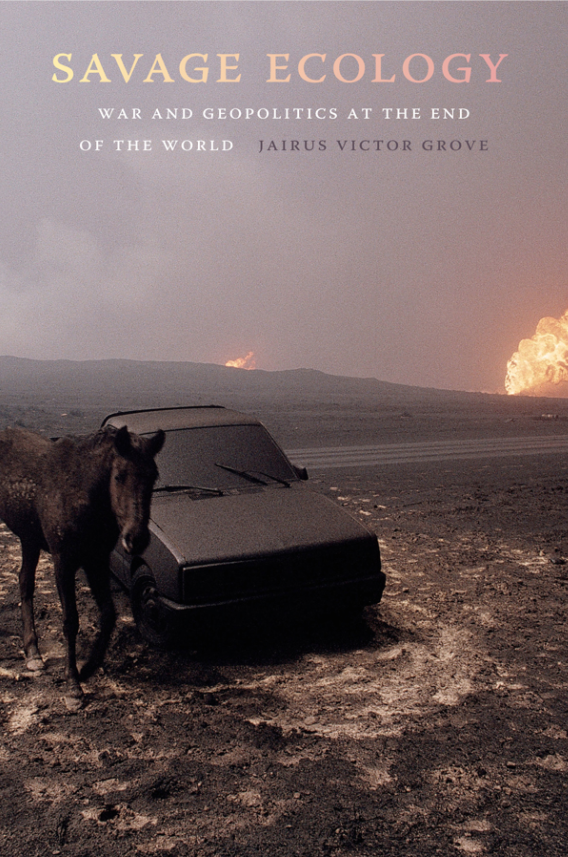

by Jairus V. Grove. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019, 368pp. ISBN: 978-1-4780-0484-4

Welcome, reader, to a new experience for the Security Dialogue blog. While we will continue to feature standard book reviews, in our book club reviews we present a novel kind of in-depth engagement with interesting books. First out is Jairus Grove’s recently-published Savage Ecology: War and Geopolitics at the End of the World (Duke University Press, 2019). Adam Freeman’s response essay draws on many of the themes and threads of Savage Ecology, but steps out of the constraints of the standard book review to creatively play with key ideas from Grove’s text. To provide context for the work itself, this introduction will complement the video trailer in bridging between Grove’s text and Freeman’s provocation.

The ambitious theoretical project touches down empirically through a series of cases, including developments in the weapons and arrangements of war, the ecology of the improvised explosive devise, the politics of blood, and the ontology of brains.

Employing ecology as a methodology for analyzing geopolitics, Grove argues that the contemporary condition is one made by war. The crises of today follow from the political violence of the Eurocene—a concept that recognizes the erasure of colonialism and Euro-American imperialism in the “Anthropocene” (47ff). Drawing together multiple lines of historical inquiry, Grove weaves critique of industrialized warfare, colonialism, white supremacy, capitalism, and international distributions of power into a single tapestry. The ambitious theoretical project touches down empirically through a series of cases, including developments in the weapons and arrangements of war, the ecology of the improvised explosive devise, the politics of blood, and the ontology of brains.

As previous reviews of Savage Ecology have noted, the vast terrain covered in the text makes it provocative in a full sense. Taking brutal honesty as a tact for a critique of common sense, the work “makes for enlightening if not grim reading.” As an anti-positivist call for radical reimagination, Grove “is not interested in proving his assertions but instead seeks to thoroughly rethink core assumptions in IR.” And yet, as another reviewer notes, there is still much that a positivist reader may take away from such a foundation-shaking critique: “Readers wedded to positivist methodologies may not find value in Grove’s approach, though they would do well to contemplate his sophisticated methodological justifications.” As Freeman’s response essay demonstrates, the work that remains to be done in reimagining the foundational ideas of the international, of politics, and of life in the Eurocene may often take a necessarily anti-positivist form. Exploration, speculation, and critique are fundamentally entangled.

Adam Freeman’s response essay draws on many of the themes and threads of Savage Ecology, but steps out of the constraints of the standard book review to creatively play with key ideas from Grove’s text.

The first section of the book contains three chapters which set out the work’s broad conceptual foundation, first by exploring the ontology and ecology of the Anthropocene, then by arguing powerfully for the ubiquity of war within the contemporary epoch. The third chapter offers a carefully historical reading of war’s changes to describe wars of annihilation and wars of exhaustion. Part two includes a trio of chapter-length case studies—examining the martial logics of bombs, blood, and brains—before canvassing the transformational projects seeking to homogenize the world through modernism, Marxism, or militarism. Through this series, the reader sees how the crucial concepts of ubiquitous warfare, competing martial logics, and the forces of the great homogenization operate through radically different objects and through-lines. The third section posits radical approaches to change grounded first in the idea of the apocalypse and then in the figure of the freak. Searching for a new form of life within the apocalypse offers a fundamentally different project from the three described in chapter 7. We are not seeking a revolution that promises to avert the apocalypse, but the new forms of life that the apocalypse makes possible. The conclusion—as well as the dystopian vision of Los Angeles in 2061—offer a fittingly pessimistic-yet-enlightening close to the ecology of the end. Serving as a kind of commencement ceremony for Grove’s intellectual adventure, he calls for a new social science that is “uncivilized” and “committed to a feral reason” (278). In Freeman’s response essay, we can perhaps find this kind of radically other voice, similarly exploratory and entirely beyond the bounds of the classical positivist social science that Grove critiques.

Savage Ecology speaks to a wide audience of critically-minded theorists of politics, environmental studies, and international relations. Security Dialogue readers will recognize how critical security studies scholarship influenced by critical war studies and martial empiricism will benefit directly, though its bridge-building between theoretical traditions will be perhaps leave its stage-setting for interdisciplinary exchange as the book’s signature contribution.