‘Think Privacy’

Public Service Announcements by the Privacy Gift Shop

©Adam Harvey 2016

Adam Harvey is an award-winning artist and researcher based in Berlin. His work has been widely covered in such publications as the New York Times, CNN and the Huffington Post, and has also been cited by critical theorists such as Grégoire Chamayou and Derek Gregory. Harvey’s work explores the societal impacts of networked data analysis technologies with a focus on computer vision, digital imaging technologies, and counter surveillance. In particular, Harvey is interested in the question of how fashion can be used to address ‘the rise of surveillance, the power of those who surveil, and the growing need to exert more control over privacy’ (Harvey 2012).

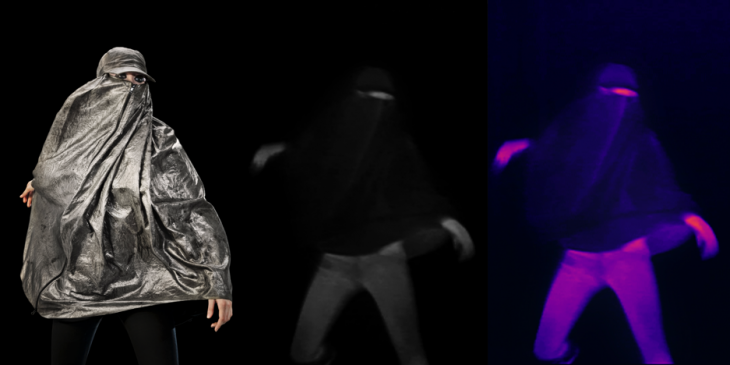

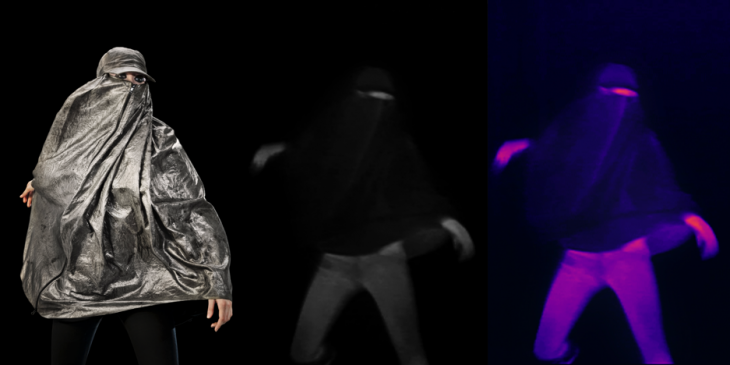

To quickly summarize his career thus far, Harvey’s projects include CV Dazzle, camouflage from computer vision; Stealth Wear, his ‘Anti-Drone’ fashion range, and the Privacy Gift Shop, an online marketplace for counter-surveillance art. For his Stealth Wear collection (2012), Harvey fabricated a set of clothing inspired by traditional Islamic dress from silver-plated fabric that reflects thermal radiation, enabling the wearer to avert overhead thermal surveillance. The metal-plated fibres reflect and diffuse the thermal radiation emitted by a body, thereby reducing the wearer’s thermal signature under observation by a long wave infrared camera (Harvey 2012). This range of anti-drone clothing is available for purchase online, alongside other works of counter-surveillance art, at Harvey’s Privacy Gift Shop (https://privacygiftshop.com). In the years since it has been produced, the Stealth Wear collection has been the subject of features in the New York Times (Wortham 2013), Washington Post (Priest 2013) and Der Speigel (Backovic 2013).

If a range of artists such as Trevor Paglen, Mahwish Christy and the collaborative art installation #NotABugSplat (https://notabugsplat.com) undoubtedly address similar questions of the ethico-political status of drone warfare, surveillance and data collection, what arguably distinguishes Adam Harvey’s work in this field is its specifically non-military, or domestic, focus. Grégoire Chamayou (2015: 203-4) provides this description of his work in Drone Theory: ‘One of the questions that arises is whether societies that have, for the time being, failed to rule out the use of this type of technology in wars waged on the other side of the world will eventually realize, perhaps with a jolt, that this technology is designed to be used on them too, and whether they will mobilize themselves to block its use. For it is important for them to become aware that a future of video surveillance with armed drones awaits us if we don’t prevent it. As a last resort, there is always the possibility of purchasing anti-drone clothing, such as that invented by the artist Adam Harvey. It is made from a special metallic fabric that renders the body practically invisible to drones’ thermal imaging cameras’.

In his interview with Antonio Cerella, Adam Harvey discusses the conceptual origins and reception of his work, its relationship to critical theory on drones, surveillance and biopolitics by figures like Chamayou and Gregory, the growing militarization of the domestic sphere and, more widely, how art can be used to – playfully – resist or challenge what he calls the fatalism of living under the gaze of domestic drone surveillance.

Antonio Cerella (AC): In recent years, your work has become increasingly influential in theoretical and philosophical circles – Grégoire Chamayou refers to your anti-drone camouflage in his Drone Theory (Chamayou 2015). To what extent are you aware of, or interested in, contemporary theoretical debates about biopolitics, drone theory, surveillance and security studies? Do they inform your work at all?

Adam Harvey (AH): Theoretical debates around surveillance are of great interest to me, but I’ve intentionally unhinged myself from thinking through the more historical part of these debates because I think the current state of surveillance and security is mostly unprecedented.

For example, Bentham’s Panopticon is of limited value in thinking about how social media is designed to accumulate data that’s used to train neural networks which are eventually licensed to government surveillance programs. And the Orwellian concept of Big Brother seems to anesthetize more complex discussions about computer vision being used to infer sexuality, criminality, or one’s psychological state.

As an artist, I see an opportunity for imaging new ways to represent the current state of surveillance, if it can even be called that. We are being observed by drones in many ways that we can’t know. And my project Stealth Wear (Figure 1) was about asking what are the limits of perceptibility – how do you know how we’re being looked at?

Figure 1 Stealth Wear: ‘Anti-Drone’ Burqa

Photo: ©Adam Harvey 2013

Materials: Burqa with silver-plated rip-stop nylon exterior and black silk interior.

Credits: Engineered by Adam Harvey. Designed by Adam Harvey and Johanna Bloomfield.

Model: Tate

One of the biggest challenges in discussing topics related to surveillance technologies is to avoid becoming fatalistic. My work aims to imagine new and expressive ways of adapting to this environment. In my own work, there is an object attached to it that is a ‘discussion-generator’ that people can easily refer to. From my perspective, it’s important to use wording that is appealing and provocative, and to frame the work so that there is an overlap with different circles, because the most important thing is what happens next, once the project is activated.

Only after working on these projects have I discovered, and enjoyed, becoming involved in actual contemporary discussions about drones, which I’m grateful to be included in. For me, experimental art projects become a gateway to other forms of related knowledge.

AC: An important theme informing much of the research on drones is the question of what happens when military drones come ‘home’ and begin to be deployed by domestic law enforcement agencies, immigration and border patrol services and so on. According to Chamayou, your work addresses the kind of society which has finally realized that the drones they are using in other parts of the world are designed to be used on them too – that a future of civilian surveillance by armed drones is here. For example, it has recently been reported that the Metropolitan Police in London are now using drones equipped with thermal imaging technologies for counter-terrorism purposes and, as Arthur Bradley and Oliver Davis discuss in their contributions to Security Dialogue, last year in Dallas the police killed a suspect by using a robot bomb (see also Graham 2016). Could you say something about how your work addresses this ‘militarization’ of the domestic sphere? Does it challenge that process? Or perhaps even reinforce it by encouraging civilians to adopt processes of camouflage?

AH: I think the reality is that dense urban areas have become military sites. It’s not a pleasant thought, but it’s how adversaries have adapted to asymmetrical military power, by advancing their mission into vulnerable non-militarized areas. The response from national security agencies has been to infiltrate communications, and to create deterrence through surveillance accountability. In New York City, where I previously lived, armed soldiers, bomb-sniffing dogs, and cell phone interceptors are a regular part of life. In 2012, when I began research and development on Stealth Wear, it seemed clear that drones were an inevitable next step once the economics worked out.

In my work, I encourage people to engage with, but essentially resist militarization, by adopting camouflaging techniques to modulate their visibility and hopefully mitigate the negativity of this militarization. The big challenge is to confront the preexisting narratives of privacy-paranoia.

So, the tension is: ‘do I accept this garment at the risk of being labelled paranoid’ or ‘do you embrace it as a fashion-forward concept?’ I tell people that you may only wear a tuxedo once or twice a year, but it’s still a great garment. So, if your rationale is that you’re okay with this garment that you wear once a year, then maybe it’s okay that you wear a camouflaging garment once a year if you want to evade thermal surveillance. But I guess it’s not that simple because it’s still tied up with the dangerous idea of ‘why do you want to hide?’, instead of thinking about it as an act of protection or defense. In some ways, that’s what fashion is: a kind of defense against categorization. Fashion gives you control over how people interpret you.

AC: What do you mean by protection against categories and categorization? It seems that this is related to your current work as well.

AH: Fashion gives you the ability to role-play and to shape-shift between social classes. By appearing in different garments, you can convince people that you belong to a different social class. There are different types of camouflage and one of them is social camouflage where I try to blend in to a crowd of really smart people when I’m not smart by wearing smart clothes. Or the opposite, that you dress down as an undercover agent wearing a T-shirt, carrying a newspaper, with a baseball hat on. These are equally valid forms of camouflage that aren’t seen as military, but can be still used in military ways: covert agents deploy a very basic street fashion to camouflage them. Fashion is an integral part of deception, both for civilian and military appearance.

AC: Why is the idea of camouflage so important to your work? In your work, it sometimes seems as if we can’t really stop or block surveillance as a society – the best we can do is hide ourselves as individuals or even run away. Is this the only solution to the kind of categorization you’re talking about?

AH: I agree that we can’t stop surveillance. I think this would be an unattainable goal and this is where surveillance fatalism re-emerges. It’s not possible to opt out or hide completely. Framing it this way guarantees failure. However, there is still a lot of room to be expressive and successful in defeating, blocking, or reducing certain kinds of surveillance. In a way, both fashion and camouflage are about staying one season ahead of the latest trends.

There is an interesting story about the word ‘camouflage’. In the early 1900s, Theodore Roosevelt considered it as a ‘form of effeminate cowardice, a mere defensive strategy [that] all but announced an unmanly desire to hide instead of fight’ (Elias 2016). Throughout the early 20th century camouflage quickly proved useful and by the end of World War II it had finally evolved into sign of humanity’s increasing intelligence – of our ability to outwit our opponents, outmaneuvering their sensory or perceptual strategies.

I find it strange that we don’t see the same connection happening with privacy right now. In the beginning of this century, there was a lot of negativity around the words “hiding” and “privacy”. And now in 2017, we’re beginning to see the same situation unfold: privacy is increasingly becoming a sign of intelligence.

AC: So, you’re putting forward a reverse argument. You’re saying that in the last two centuries, camouflage has been used for military purposes, but we can use it for civilian purposes in order to get some privacy back?

AH: Right. I’m also saying that embracing military-strategy surplus is not taboo. I think a lot of people aren’t comfortable engaging with military culture. But, if it can be reformulated in a more fashionable way, then people will be more willing to engage with topics such as thermal surveillance or facial recognition. When I started working on CV Dazzle in 2010, face detection was mostly linked to national security, not consumer products. Subverting it meant also meant subverting national security. Similarly, in 2012-2013, the primary use of thermal drone surveillance was to locate foreign enemy combatants. Now both are a daily part of the UK’s domestic surveillance program (Davis 2017)

AC: In your project CV Dazzle (Figure 2), you show how some very lo-tech fashion modifications that anyone can make can be used to overcome hi-tech surveillance technologies. You can even buy some of the technologies you develop on your website the Privacy Gift Shop (Figure 3). Another theme from our recent work in Security Dialogue is the extent to which the ever-increasing penetration of drones into the domestic sphere might also create the possibility of new forms of civil resistance. To what extent do projects like CV Dazzle describe a politics of ‘everyday resistance’?

Figure 2: CV Dazzle Look 3

Photo: Adam Harvey

Model: Jude

Hair: Pia Vivas

Art Direction: DIS Magazine

AH: That’s a great way to look at it. When you put clothes on in the morning, when you style yourself to go out, you need to consider the new environments of mass surveillance we’ve created and aren’t easily escapable. Machine vision is a reality: you’re being observed and analyzed and will be continually analyzed for the next decades whenever that information is stored on a database. How do you reflect that in the way that you appear throughout time? Well it’s not possible to see into the future, but it is possible to see into the present, to a certain degree. A lot of the important information on what’s happening in the computer vision industry is buried in long technical papers, but as you become more aware, the decisions you make in the morning – everyday resistance – will begin to affect the way that you dress. You start dressing for a machine-readable world.

AC: Can you say a bit more the relationship between everyday resistance and the idea of play? It seems you are talking about something slightly different from the militarization of the private sphere. It’s not about militarizing yourself, it’s more about a playful mode of resistance.

AH: Yeah, I like to avoid thinking of these projects as resistance. In fact, they’re the opposite. Where resistance costs you, these projects are designed to afford new opportunities. I mean, they’re politically-motivated and serve the same purpose, but I absolutely want to avoid creating more resistance for people.

AC: How, if at all, do you see the political debate around drones and surveillance changing in the next few years? Do you envisage any kind of concerted attempt by governments to challenge the monopolies of the big tech companies? Is the idea of ‘a human right to our own data’, for example, possible or desirable?

AH: I think we’re only at the beginning of learning what it means to be digitized at varying resolutions. Take the capabilities of cameras now (a lot of my research is on visual information) – it’s astonishing how much you can learn through aggregate information with neural network classifiers. For example, with a 6 x 7 pixel face image, you can do facial recognition on a group of 50 people with 95% accuracy. At 100 x 100 pixels, you have enough information to recognize hundreds of thousands of individuals. But even with 11 x 11 pixels, it’s now possible to resynthesize a low-resolution image into a higher-resolution image, meaning 11 x 11 pixels is nearly enough for some facial recognition applications.

I can imagine an EU-centric push towards a human right on protection of personal visual data. It’s astonishing how much biometric information can be obtained remotely without one’s consent. For example, it’s possible to extract your heart rate and skin conditions and iris data from over a hundred meters away. This information could eventually be augmented by multispectral sensors that can measure body temperature (thermal) or vein patterns (infrared). But first we need to develop a better understanding of what exactly we mean when we say ‘face’ or ‘biometric’. Do we mean to include psychological inferences and heart irregularities along with facial recognition?

AC: Who has the upper hand at this moment in these new forms of visual recognition technologies? The private companies or the government? Or are they working together for security purposes?

AH: They are both working together. I think the corporations have the upper hand of talent, but not funding or hardware. The NSA will always be years ahead of corporations with their computational capabilities. But this could be changing with regards to quantum computing. You can see evidence of collaboration in the Snowden documents, which reveal that the NSA received a license for facial recognition software called PittPatt from Google. But PittPatt was a start-up from Carnegie Mellon. And Carnegie Mellon receives significant funding from the Department of Defense, DARPA, and IARPA. Depending on how you look it, it’s one ecosystem.

AC: This is very much related to the idea of the fungibility of technology. The government only funds those projects that are fungible for military purposes. When a technology is invented, it has to be functional for security purposes, otherwise they would never invest any money in it.

So, anyway, you are currently in London for the opening of a new project. Could you tell us a little about this and your future plans?

AH: Recently, I’ve come to the realization that visual machine communications are an integral part of how the new world is operating. I used to approach computer vision and surveillance from the perspective of counter-surveillance and avoidance. But now this limits my ability to communicate. I’ve now changed my approach and I’m embracing these technologies, because as I understand that they’re here to stay. I’m thinking about how they can be applied to helping human rights groups, how they can be used by groups like Forensic Architecture. To ignore the technological capabilities that enable you to keep protesting surveillance is the wrong strategy moving forward. I now believe visual machine communications to be an essential way of understanding the world and communicating information.

The work I am presenting here in London is called MegaPixels. It’s a real time facial recognition query into the databases that are used to train facial recognition software. Most people don’t know that they might be in these databases because the databases are created from social media images. They are created from photos posted online. The installation currently uses MegaFace, which is the largest publicly available facial recognition training dataset. When you walk up to the installation you’ll see the highest confidence matches from the dataset, and there is a small chance that you may find yourself. Out of the billions of people in the world, this dataset has 672,000 people. By chance, at least 2 people during the exhibition were positively identified in the dataset.

AC: Can I ask you a very difficult final question? I don’t know if you are familiar with the work of the French philosopher Michel Foucault, but I wanted to raise what I think might be his response to the situation you are describing, namely, that we are very easy to profile because we are so easily identifiable through these new media technologies, social media, Facebook, Google, etc. Is this because of our behaviour, or is it because the system compels us to behave in a specific way which can be recognized? I think Foucault would say the latter: it’s not because we are always very similar to ourselves but because the system provides us with very detailed, structured pathways which we need to follow to behave as ourselves. We have to invent ourselves by means of the system and that is the reason why we are recognizable. So, in a way, the only way out would be to unplug the system.

AH: This is reality, and you can certainly see it with facial recognition and facial analysis. People become recognizable as the identities they bought into. Faceception (www.faception.com) is one company that clearly shows this feedback loop. It’s a filter bubble effect in the physical world. We can become trapped in the datasets of our former selves.

References

Backovic, L (2012) ‘Hier kommt der Drohnen-Schutzanzug’. Spiegel online, 17th January. http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/stealth-wear-modedesigner-adam-harvey-stellt-drohnen-schutzanzug-vor-a-877844.html (accessed 24.05.18).

Elias, Ann (2016) ‘Camouflage and its impact on Australia in WWII: An Art Historian’s Perspective’. Salus Journal. Vol 4, No. 1.

Chamayou, Grégoire (2015) Drone Theory tr. Janet Lloyd, London: Penguin.

Davis, Caroline (2017) ‘London could get 50m armed police base to tackle terrorism’, The Guardian, 11 September. Accessed 01.11.17. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/sep/11/london-new-armed-police-base-met-tackle-terrorism

Graham, DA (2016) ‘The Dallas shooting and the advent of police killer robots’, The Atlantic http://www.theatlantic.com/news/archive/2016/07/dallas-police-robot/490478/ (accessed 01.11.17).

Harvey, A (2013) https://ahprojects.com/projects/stealth-wear/ (accessed 24.05.18).

Priest (2013) ‘Government surveillance spurs Americans to fight back’, Washington Post, August 14. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/government-surveillance-spurs-americans-to-fight-back/2013/08/14/edea430a-0522-11e3-a07f-49ddc7417125_story.html?utm_term=.45579b1d8d92 (accessed 24.05.18).

Wortham, J (2013) ‘Stealth Wear aims to make a statement’, New York Times, June 29. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/30/technology/stealth-wear-aims-to-make-a-tech-statement.html (accessed 24.05.18).

This interview is a part of the Security Dialogue special compilation ‘Droneland’ edited by Arthur Bradley and Antonio Cerella. An introduction to this compilation can also be found on this blog, and two peer reviewed full-length articles: Deadly force: Contract, killing, sacrifice by Arthur Bradley and Theorizing the advent of weaponized drones as techniques of domestic paramilitary policing by Oliver Davis were published in the 2019 August issue 50(4) of Security Dialogue.