Three scholars involved with climate and security projects at PRIO have been included in the author panel for IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report. From left: Halvard Buhaug, Elisabeth Gilmore and Tor A. Benjaminsen.

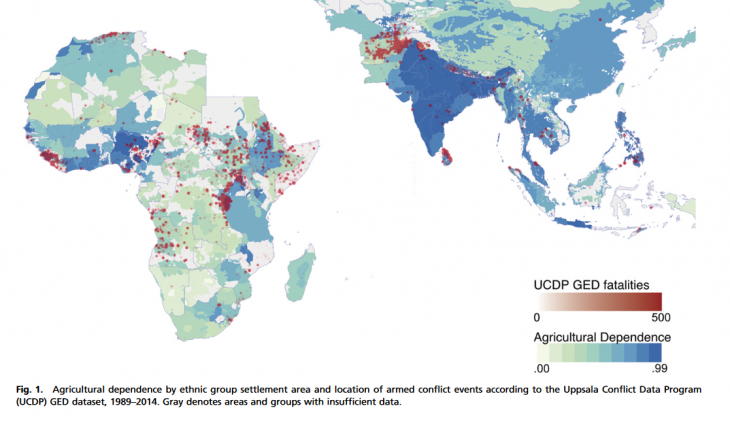

I reported in this Blog on 25 January on the prospects for coverage of the link between climate and conflict in the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), scheduled for release in 2021–22. The number of chapters in the report for Working Group II has been cut to 18, compared to 30 in AR5. The new report will not have a separate chapter on human security. Nevertheless, we must expect that the relationship between climate change and conflict will be addressed in the report, as was the case in all the three preding assessment reports.

A long process for naming Coordinating Lead Authors, Lead Authors, and Review Editors of the three Working Groups is now complete. A total of 2912 experts were nominated before the deadline on 27 October 2017. Nominations were made from national government focal points, observer organizations, and IPCC Working Group bureau members. There were no less than 2858 nominations from 105 countries for the three reports, WG I on the physical science basis, WG II on impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability, and WG III on mitigation, with some overlap. Altogether, 721 authors and editors from 90 countries have been invited. Their names can be downloaded from here.

The lists of authors and editors reflect several concerns, including international academic stature, regional expertise, representation for developing countries and economies in transition, as well as the need to balance experience with previous IPCC reports with fresh perspectives from new authors.

Despite the disappearance of a designated human security chapter in AR6, the author teams include several conflict experts, among them Tor Arve Benjaminsen of the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and Thomas Bernauer of ETH Zürich (both for Chapter 1, Point of departure and key concepts), Elisabeth Gilmore of Clark University (for Chapter 14, North America), and Halvard Buhaug of PRIO (for Chapter 16, Key risks across sectors and regions). In addition to Buhaug, Benjaminsen and Gilmore are currently attached to PRIO in adjunct positions and all three are part of a Research Council of Norway-sponsored research project on Climate Anomalies and Violent Environments. The Norwegian Environment Agency has posted a list of all AR6 authors affiliated with Norwegian institution, available from here.

In the previous Assessment Report (AR5), statements about the effects of climate change on conflict were not limited to the Human Security chapter but also appeared in other chapters, such as the Africa chapter. Chapter 16 in AR6 will presumably play a decisive role in making sure that there are not too many inconsistencies between the different chapters.