In the wake of mass violence, holding every complicit person or group accountable is impossible. Rwanda discovered this after its 1994 genocide with an estimated 1,000,000 collaborators. Many still try to make sense of accountability for the Holocaust.

Over the years individuals (Adolf Eichmann, Klaus Barbie, and others) have faced trial and in the 1990s a slew of corporations (banks, insurance companies, and others) found themselves interrogated over their roles during Holocaust. Ultimately, only a few face trial. How are these few selected? Are they the guiltiest and does their conviction contribute to long-term security?

Former Secretary of State Madeline Albright supports convicting the leaders and expunging the collective; holding everyone accountable prevents the society from moving forward. Scholars share Albright’s concern; John Braithwaite expressed concern about ‘shaming machines’ and Martha Minow about ‘blame cycles’ which promote revenge and potentially lead back into violence.

Those held accountable are not always the guiltiest or the most likely to promote future violence. They embody certain attributes helping them stand for the collective. They serve as ‘ideal perpetrators.’ Criminologist Nils Christie wrote about the ‘ideal victim’ as someone purely innocent and free from blame. As an example, Christie offers an old lady coming home mid-Saturday after caring for her sick granddaughter and getting mugged. Now, we need a perpetrator purely evil enough to complete the scene.

An ‘ideal victim’ Source: Béria L. Rodríguez [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

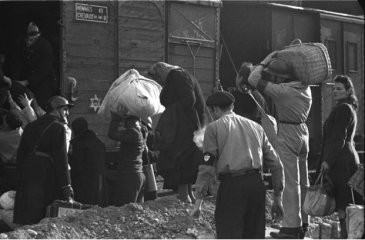

To demonstrate, I use the example of the French National Railways (SNCF), which for the past decade has found itself embroiled in lawsuits and legislative battles in the U.S. over its role in the World War II deportation of Jewish deportees towards death camps.

Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-027-1477-19 / Vennemann, Wolfgang / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons

When we focus on one perpetrator, many other guilty parties hide in the shadows, like the guard in the photo above. Furthermore, by isolating the perpetrators always as someone or something outside ourselves, we skip the important work of considering how we, our policies, our societal values, etc. contribute to mass violence. Without this work, we will likely find ourselves in conflict again.

Scholar Vivienne Jabri argues the creation of these victim and perpetrator groups is violence. Once we begin to exclude members of society, we begin the process of legitimizing violence against them. We then become the agents of suffering and the cycle continues. If the processes of separating victims and perpetrators is violence, is it not vital to understand how we select our perpetrators?

Further reading:

Albright, Madeline, Conversation after presentation From Words to Action, the Responsibility to Protect, The United States Holocaust Museum, July 23, 2013.

Braithwaite J (2004) Restorative justice: Theories and worries. Visiting Experts’ Papers: 123rd International Senior Seminar, Resource Material Series 63: 47-56.

Christie N (1986) The ideal victim. In: Fattah EA (ed.) From Crime Policy to Victim Policy. London, UK: Macmillan, 17-30.

Federman, Sarah. The Last Trains to Auschwitz: The French National Railways’ Role in the Holocaust and the Struggle to Make Amends. (Under review)

Jabri V (1996) Discourses on Violence: Conflict Analysis Reconsidered. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Minow M (1999) Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History after Genocide and Mass Violence. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.