In late December 2020, former US president Donald Trump pardoned the four Blackwater private security contractors involved in the Nisour Square incident, a 2007 shooting in Baghdad that resulted in the death of 14 Iraqi civilians. Although Joe Biden’s administration is unlikely to follow his predecessor in condoning such actions, the United States (US) reliance on private military and security companies (PMSCs) as providers of logistical support, training, and armed protection is not going to subside. PMSCs have become an indispensable force multiplier for both the US and many other advanced military organizations.

This problematic end of the Blackwater judicial saga is a forceful reminder of the importance of studying PMSCs, their regulation, and their marketing strategies. Previous scholarship has dedicated some attention to the discourses used by PMSCs to portray themselves as legitimate security providers. These studies, however, have relied almost exclusively on the analysis of written documents, overlooking PMSCs’ non-verbal communication. In my latest article, available through open access, I conduct the first analysis of the visual discourses used by the international private security industry by examining a basic and yet unexplored form of communication: PMSCs’ logos.

Despite their growing interest in visuality, international relations scholars never examined logos. This neglect is worth addressing not only due to logos’ presence in every aspect of our daily lives. Besides serving as marketing tools, logos are also symbolic acts that shed light on the shifting identities and legitimization strategies of contentious industries like PMSCs. In the article, I leverage visual semitiocs to argue that logos serve different purposes and reflect different trends:

- Camouflaging PMSCs in the broader business landscape by hiding the nature of their services

- shifting the blame attached to rogue, offensive security providers

- mirroring a shifting customer base to gain prospective clients’ trust

- reflecting PMSCs’ socialization to the logics of appropriateness of the business world

These overlapping processes have reshaped PMSCs’ visual identity, revealing the existence of three phases in the evolution of the international private security industry.

During the inception of today’s international private security market, companies emerging from the shadiness of Cold War mercenary ventures embraced low-profile brands, camouflaging themselves behind logos and names with no direct connection to military activities. Consider the first commercial providers of combat services, the now-defunct PMSCs Executive Outcomes (EO) and Sandline. In their effort to mimic mainstream business providers to increase their legitimacy, EO and Sandline adopted their own logos. Although the shape and balance between text and images reflects military tabs and coats of arms, neither the logos nor the names chosen by Executive Outcome and Sandline directly reveal anything about the services they provided.

After the 2003 invasion of Iraq, new firms mostly formed by retired US military professionals entered the market. Such companies sought to enhance their competitiveness through more proactive branding strategies, primarily targeting contracting officers in the US government by signalling the ability to operate in conflict zones. Accordingly, their logos borrowed heavily from the visual identity systems of US armed forces, displaying colours and symbols traditionally associated with the military profession.

Consider Blackwater, which marketed itself as the provider of assertive protective services aimed at proactively deterring attacks. Its logo – a black bear’s paw encircled by a red shooting frame – perfectly epitomized Blackwater’s aggressive security model. By tapping into the world of hunting and professional team sports, such an iconic logo effectively resonated with US consumer mythology, conveying a familiar message to the population of male American individuals with a military background who could either hire Blackwater or work for them. The Nisour Square incident, however, irreparably tarnished the Blackwater brand, which turned into a symbol of the widespread culture of impunity among US contractors in Iraq. Public outcry eventually forced the US government to cancel its contracts with Blackwater.

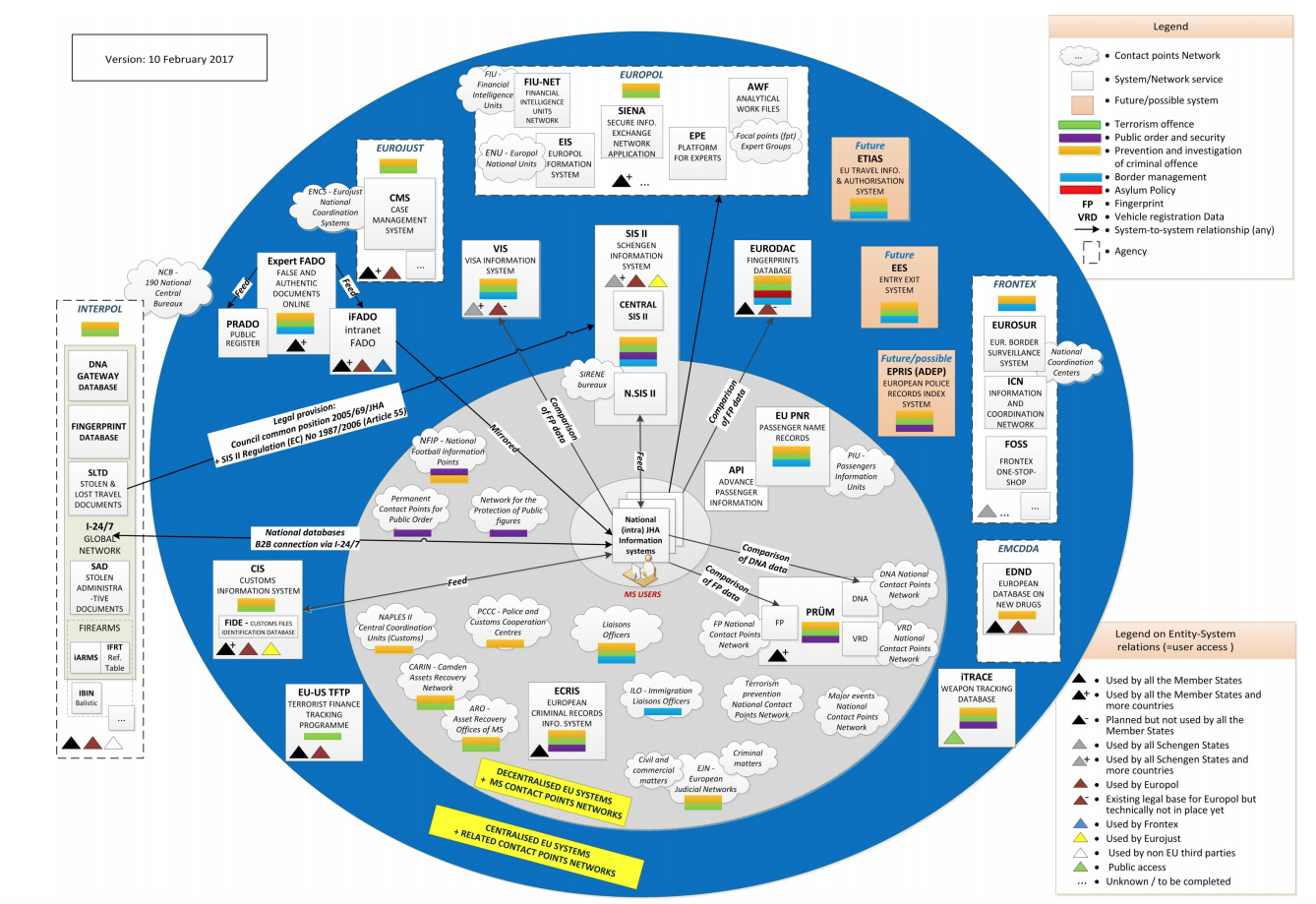

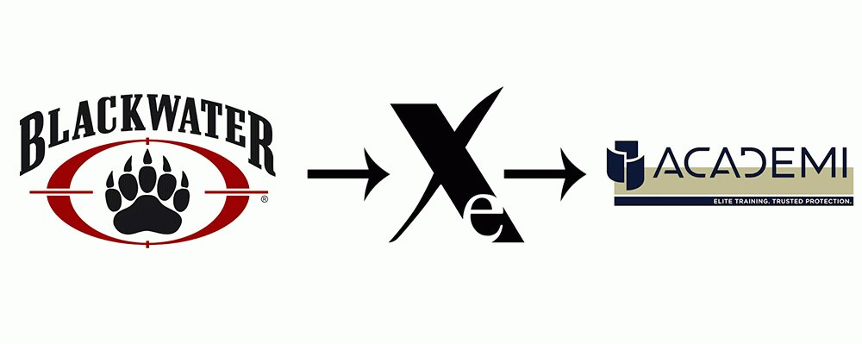

The firm, which made around 90% of its revenues from federal contracts, sought to disperse the blame arising from scandals through rebranding. As illustrated in Figure 2, Blackwater was first renamed Xe, after the inert gas xenon, and then Academi. According to the CEO, the firm was named after Plato’s academia to capture its new corporate identity as a provider of elite training. In an attempt to escape the stigma attached to Blackwater, Academi chose a much more low-profile, defensive symbol.

Figure 2: from Blackwater to Academi

As Blackwater’s brand had become ‘toxic’, distancing themselves from the company’s aggressive private security model also became essential for other PMSCs to safeguard their business prospects. Accordingly, large firms signed codes of conducts and subscribed to multi-stakeholder initiatives like the International Code of Conduct for private security providers, thereby signalling their willingness to exclusively provide tightly regulated defensive services.

During this market consolidation phase, the shrinking demand for private security in Iraq and Afghanistan strengthened the shift towards more low-profile logos. Symbols and colors that were effective at attracting contracting officers from the US Department of Defense by tapping into US military visual identity systems and pop culture became detrimental to market-diversification imperatives. Most notably, large extractive corporations – themselves wary of reputational damage and public boycotts – would flag firms showcasing military symbols and colours as potential future liabilities, expecting the PMSCs they hired to display logos as professional as their own.

Rebranding, however, did not solely reflect the explicit goal of camouflaging the true nature of PMSCs’ activities, shifting blame or explicitly mirroring prospective customers. In many cases, logos evolved in accordance with the industry’s changing structure and employee population. The growth experienced in the 2000s allowed many firms to consolidate, developing more sophisticated corporate structures. Owing to mergers and acquisitions, many smaller PMSCs became parts of larger, publicly traded conglomerates or subsidiaries of corporations selling a wider array of services. Accordingly, firms previously consisting only of a few retired military officers to be summoned at need started to employ a larger body of professionals with a business background, including accountants, analysts, lawyers and marketing experts. As PMSCs increasingly developed corporate organizational cultures, amateurish logos displaying battlefield paraphernalia started to be seen as inappropriate not only by stakeholders and prospective customers, but also by firms’ own executives and employees.

The converging influence of camouflaging, blame-shifting, mirroring and corporate socialization reshaped PMSCs’ visual landscape, informing a shift away from the use of military symbols and colors. As a result, the population of PMSCs belonging to the International Security Operations Association (ISOA), the largest industry, changed significantly over the years. While they did not completely disappear, offensive weapons like swords and rifles were replaced by defensive symbols like shields or more minimalist, low-profile business logos, while khaki, military green and red were largely substituted by more conventional business colors like blue and silver.

Despite their low information bandwidth, logos are symbolic acts providing important insights into organizations’ legitimizing discourses and shifting identities. International relations scholars should therefore pay more attention to the logos of business entities and non-governmental organizations alike. Scholars of private security, on the other hand, should continue to investigate the evolving identity, legitimization strategies and regulation of PMSCs.

Figure 3: from MPRI to Engility

Figure 4: SOC’s old (left) & new (right) logo

Figure 5: from International Peace Operations (IPOA)to ISOA

While Defense and State department regulations, multi stakeholder initiatives and market pressures have encouraged tighter compliance with international and domestic law, some accountability gaps remain. Over the last few years, countries like Russia and the United Arab Emirates increasingly rely on PMSCs that do not shy away from providing direct combat services in theatres like Libya, Syria, Ukraine and Yemen. As concerns about the rise of right-wing extremism among US military personnel and veterans increase, Trump’s pardon is in danger of hindering the progress in the regulation of US-based PMSCs as well, eroding their commitment to provide tightly regulated defensive services only.