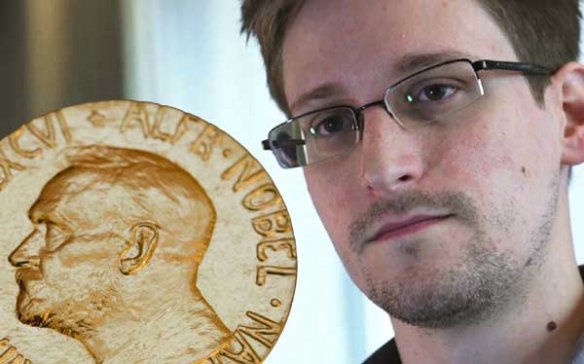

Edward Snowden’s nomination for this year’s Nobel Peace Prize has stirred controversy in Norway and internationally. Is Snowden a (US) traitor or a (global) saviour? Will Norway allow him to receive the prize, resisting US demands to arrest and hand him over?

Along with previous years’ nominations of Julian Assange and Bradley (Chelsea) Manning, Snowden’s candidacy brings attention to one of the largest threats to liberal societies as we know them: traditional human – hence limited – intelligence is replaced or supported by seemingly limitless technology, electronic surveillance and big data. The debate about information technology and cyber warfare leads us to consider the value of whistleblowing to democracy, individual freedom and privacy.

Along with previous years’ nominations of Julian Assange and Bradley (Chelsea) Manning, Snowden’s candidacy brings attention to one of the largest threats to liberal societies as we know them: traditional human – hence limited – intelligence is replaced or supported by seemingly limitless technology, electronic surveillance and big data. The debate about information technology and cyber warfare leads us to consider the value of whistleblowing to democracy, individual freedom and privacy.

Contrary to Assange and Manning, Snowden has taken seriously the possibility that his leaks can compromise the security and wellbeing of individuals. This, in my opinion, makes his candidacy the only justifiable of the three. His actions are still controversial, however, and many – including 2009 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Barack Obama – consider them acts of treason. Indeed, Snowden is charged with espionage by the USA, but as he has not set foot on US (or allied) soil, he has so far eluded detainment. He was reportedly granted a three year asylum in Russia in August this year.

The question, then, is what would happen were he to be awarded the prize and come to Norway to receive it in December. This has been a topic of heated debate in Norway this year, picking up recently, but on the agenda since Socialist Left parlamentarians Snorre Valen and Bård Vegar Solhjell announced their nomination back in January. Despite not necessarily supporting all of Snowden’s leaks, they find

that the public debate and changes in policy that have followed in the wake of Snowden’s whistleblowing has contributed to a more stable and peaceful world order. His actions have in effect led to the reintroduction of trust and transparency as a leading principle in global security policies. Its value can’t be overestimated.

Snowden has also been nominated by others, including Norwegian Professor of Law Terje Einarsen, who argues along the same lines as the above, but also with direct reference to the “fraternity among peoples” from Nobel’s will (translated as “…between nations” in this English version, but “folkens forbrödrande” in the original Swedish text). Einarsen’s nomination has since been supported by multiple Professors of Law in Norway, as well as the International Commission of Jurists.

There is disagreement in Norway over whether a prize to Snowden would harm US–Norway relations (echoing the consequences vis-à-vis China after the prize to Liu Xiaobo in 2010). Some politicians have argued that a prize would be inappropriate given the fact that the USA as a country based on rule of law has charged Snowden with felonies under the Espionage Act. The intricacies grow the closer Snowden gets to the prize and to Norway: If Snowden sets foot on Norwegian soil, Norway would, in principle, be committed to detaining and extraditing him to the United States. (The same would apply to all individuals under charge or wanted by countries with which Norway has extradition agreements, with a few exceptions.)

There is equality before the law, and a Peace Prize laureate would be no different from any other individual, MP Michael Tetzschner (Conservatives) has stated. Tetzschner has also, however, been critical of the Snowden nomination in general. Although crimes of a more political nature (such as espionage and treason) are not covered by the exchange treaty between the USA and Norway, Snowden is also charged with theft (of national defence information), which is included. But there are other exceptions and provisions: Firstly, before extraditing, Norway would have to be certain that there is no risk of the death penalty or any inhumane treatment. As a whistleblower, Snowden may have the opportunity to apply for political asylum in Norway. And finally, the US charges against Snowden are based on a legal framework from 1917, which deprives the accused of a public defence, described as “archaic” by legal scholar Gjermund Mathisen.

The discussion over a potential extradition should be irrelevant to the Norwegian Nobel Committee. Were Norway to extradite a Nobel Peace Prize laureate facing charges in his or her home country, this could raise serious questions about Norway’s role as a host for the Nobel Peace Prize. It would in effect delimit the freedom of the committee to select among all candidates. The committee should evaluate Snowden’s nomination on the merits of his actions, whether he indeed is the one that has contributed the most to peace in the last year, as Nobel defined it. As was likely done in the case of Malala Yousafzai’s candidacy last year, the ramifications for the individual may be considered, but at no time should the committee be restrained by the possible ramifications for Norway.

A prize to Snowden would add to an already heated debate about the committee’s independence. I have argued elsewhere that the Norwegian Parliament, tasked by Alfred Nobel in his 1895 will, to appoint a committee of five members, ought to change its practice. Today, the committee seats are distributed among Norway’s political parties, relative to their weight in parliament. Appointed by their respective parties, committee members are most often senior party politicians, and questions can be raised about the committee member’s loyalty to Norwegian state interests in general and to their respective parties in particular. A prize to Snowden would highlight the principled problems with the current practice, and inevitably give further impetus to the call for change.