In general, religious actors are not perceived as possible contributors to civil society. In Afghanistan, where religion permeates society and politics, and where religious leaders and networks bear considerable influence, this is particularly problematic. There is a need for a thorough rethink of what civil society is, and the role of religion within it. While knowledge is deficient in vital areas, what we do know merits a thorough reorientation of policy and practice.

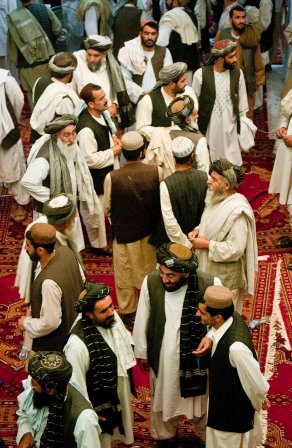

Tribal and religious leaders in southern Afghanistan, 2010. Photo: Mark O’Donald

Religious actors are under double pressure. The Taliban, as the main armed opposition, see Islam as their main source of legitimacy. Religious leaders who express support for the government, or who declare their neutrality, are subject to pressure and, not infrequently, assassination. The government and their international allies, on the other hand, are deeply suspicious of religious authority, which they tend to associate with traditionalism and backwardness, if not with radical militancy. Given the immense politicization of religion in Afghanistan, both historically and during the last three decades of war, this is not surprising. But, Islam remains a strong force in Afghan society, and current policies tend to radicalize large parts of the religious leadership, hence strengthening the militant opposition.

The insistence on a role of religious actors in civil society is controversial. Ernest Gellner, in his Civil Society and Its Rivals (Penguin, 1994) argued that the idea of a civil society is intrinsically linked to a civility norm and democratization rooted in individualization, in contrast to Islamic collectivism. Others would argue that the ulama – the higher clergy – see themselves as custodians of the law, which places them above the law. A related argument is that the ulama – being on the state payroll – lack independence. Each of these arguments have certain merits, and alert us to the danger of seeing everything religious as part of civil society. In Afghanistan, there is an institutionalized system of ulama councils, paid by the government, but a large part of the religious leaders stand outside this system. And, while it is true that Islam is a law religion, and that many ulama see themselves as its guardians, there are other interpretations and possible roles. Most importantly, religious actors fulfill genuine civil society functions, in areas such as socialization, advocacy, conflict resolution and social security.

As part of our research, we have interviewed religious leaders in the capital, and – with the Cooperation for Peace and Unity (CPAU) – conducted case studies in Kunduz and Wardak. We found that although a majority expressed positive views about the government’s development agenda. Although cautiously sceptical of the government, many believe that, as religious leaders, they could positively contribute to this agenda by generating support among the people, as well as through more direct participation in development projects. Most religious leaders, however, say they have not been invited to take part in such processes. A majority of the religious leaders interviewed – and virtually all those interviewed in Wardak – were critical of the foreign military presence. Yet, even those who were critical to foreign military assistance welcomed development projects and signaled their willingness to cooperate with them. Overall, the religious leaders find that to the extent that the government and internationals interact with them, it is to enroll their support for predetermined initiatives, but rarely in genuine consultation.

The impressions are confirmed when talking to representatives of the government and the international community. There is a great deal of skepticism of religious actors. Although there is a realization that they may be important actors at the local level, there is reluctance to give them any tangible influence over plans and programs. There is also competition about who genuinely represent civil society, as Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), despite their brief history in the Afghan context, lay claim to opportunities for funding and influence. NGOs have become agents of modernization, pushing for reform, challenging traditional norms and practices, and upsetting longstanding power structure. But, there are exceptions, where NGOs work closely with religious leaders, particularly at the local level, finding that this sort of collaboration significantly enhances their impact.

There are severe limitations in the systematic knowledge on the role of religion in Afghanistan. What is the interface between religious and other types of leaders at the local level, when and how are the former able to play an independent role? How has traditionalist Islam been influenced by Islamic radical movements, including an increasingly militant Taliban? How are Afghan religious networks embedded in transnational ones, and to what extent are non-Afghan influences the drivers of radicalization? We need to know more on these and a range of other issues.

Yet, we do know something. The virtual exclusion of religious actors in the post-Bonn process has had severe costs. Currently, religious leaders are in a squeeze between the government and the insurgency, with little space for independent action. The challenge for the government and its international actors is to start creating that space. For the government, it implies that religious actors should be taken seriously, engaging in dialogue with them before decisions are taken. For the internationals, it requires level of understanding and respect, without necessarily being at the frontlines of religious dialogue. Ultimately, we all need to realize that Islam and its leaders constitutes a force – indeed a resource – that must be an integral part of any sustainable road towards peace in Afghanistan.

- This text is published in connection with the Afghanistan Week 2015.

- This text has been published in 2009 in Afghanistan Info, a periodical edited by Swizz anthropologist Micheline Centlivres-Demont, and was recently published as part of her book Afghanistan: Identity; Society and Politics since 1980 (IB Tauris, 2015)

Further reading:

- Kaja Borchgrevink, 2007. ‘Religious Actors and Civil Society in Post-2001 Afghanistan’. Oslo: International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO)

- Kaja Borchgrevink & Kristian Berg Harpviken, 2009, ‘Afghan Civil Society: Between Modernity and Tradition’, in Thania Paffeholz, ed., Civil Society and Peacebuilding, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner

- Borchgrevink, Kaja & Kristian Berg Harpviken, 2010. ‘Afghanistan: Civil Society Between Modernity and Tradition’, pp. 235–257 in Thania Paffenholz, ed., Civil Society and Peacebuilding. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Gellner, Ernest, 1994, Civil Society and Its Rivals. London: Penguin Books

- Mirwais Wardak, Idrees Zaman & Kanishka Nawabi, 2007. ‘The Role and Functions of Religious Civil Society in Afghanistan: Case Studies from Kunduz and Sayedabad’. Kabul: CPAU