Is it just religious fanatics who blow themselves up as suicide bombers?

Bernt Hagtvet, Professor of Political Science at the University of Oslo, has been active in the Norwegian media lately, stating that only religion (he focuses mostly on Islam) brings the fervor to commit suicide attacks as part of a political struggle – or “only religious totalitarian movements have capabilities to create a fanaticism strong enough to suicide.”

This is not true.

Firstly, there is ample evidence showing that a deterministic relationship between suicide missions and having a religious agenda or ideology is wrong. It is right that more suicide bombers today belong to Islam than any other religion, but their general levels of religiosity and particularly knowledge of Islam is up for debate. Scott Akran in his article published in Science, for example, reported that suicide terrorists are generally only moderately religious, hence not necessarily the epitome of radical religious fervor. Many have tried to offer simple explanations of suicide terrorism, which is likely to be a misguided effort.

Secondly, suicide violence is used by a number of groups, not all Muslim, and not all religious. Expert on South Asian violent movements, Iselin Frydenlund, asked the timely question of whether the overriding focus on Islam for us to overlook that suicide bombings have also been carried out by Christians, Hindus and secular martyrs? Her op. ed. in the major Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet and post at the PRIO Blog point to statistics of suicide attacks that were carried out in the period 1980-2001. It shows that 60 percent of attacks were carried out in the Muslim part of the world, but that a third of these attacks were carried out by groups with a secular orientation, such as the Kurdish liberation movement PKK. The group that has carried out the most suicide attacks in the period 1980-2001 is the Tamil Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka. LTTE accounted for more than 40% of all suicide attacks during this period. While the LTTE is a secular movement, the LTTE soldiers were not Muslims, but Hindus and Catholics. For more statistics on the development of suicide terrorism, see the Global Terrorism Database.

These examples show the need for more comparative and empirical studies. More importantly, however, it shows with even more clarity the need for focus on sound evidence in the public debate. Both researchers and media should get better here. In collecting and presenting such evidence, researchers must try as much as possible to distance themselves from seeing the world through the glasses of the current day and letting the contemporary and the media focused version of reality overshadow the true nature of a phenomenon.

Benjamin Acosta, Journal of Peace Research 2016; 53: 180-196

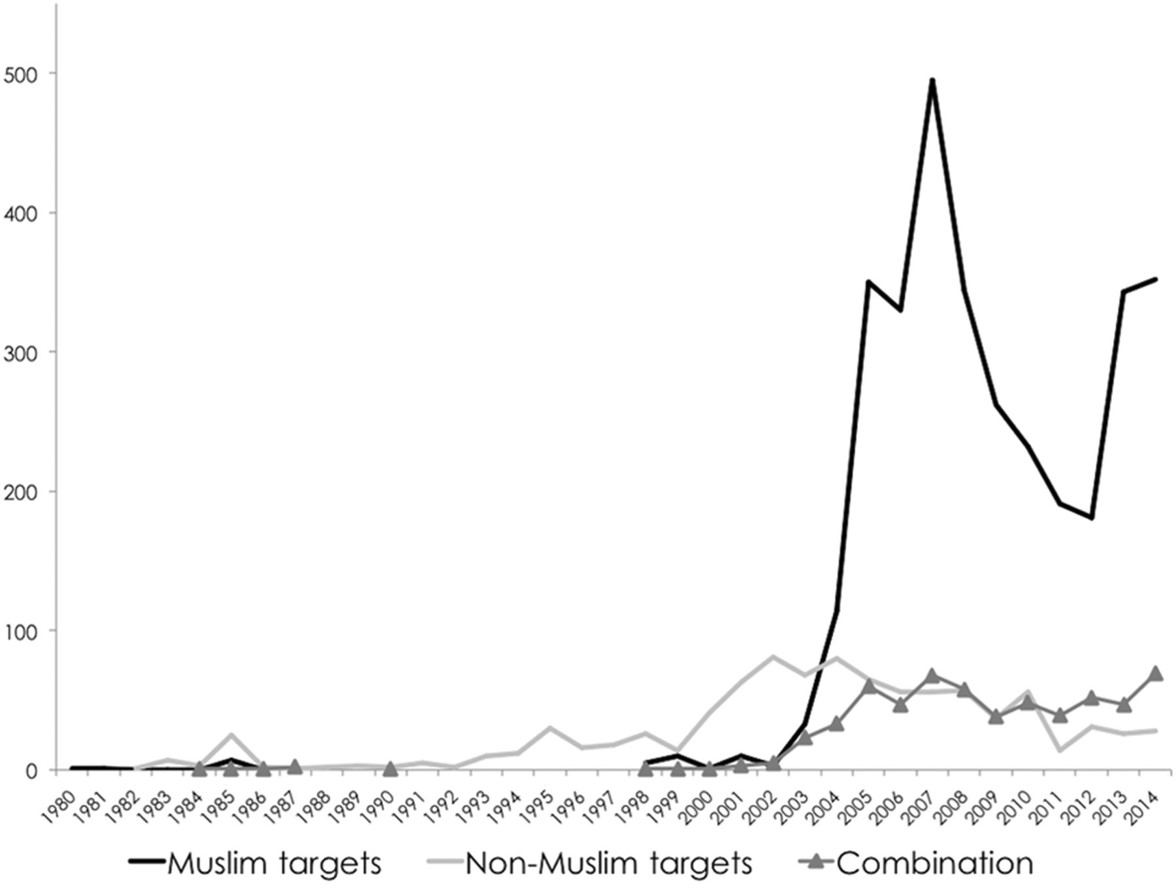

Yes, today, many suicide bombers are Muslims, and many suicide bombers refer to religion as justification for their acts. The havoc and human suffering they cause cannot be underplayed or negated. However, the victims are mostly among their Muslim brethren. Research by Benjamin Acosta, published last month in Journal of Peace Research, shows that most suicide attacks have involved an Islamist organization directly striking a Muslim target. Rather than resulting from religious fervor, Acosta argues, suicide tactics are used for organizational survival, and constitutes a “fashionable” tactic that spreads within networks of similar organizations as less powerful organizations want to increase their status by imitating more powerful groups.

Furthermore, most suicide attacks, as many as 95%, are carried out by individuals in their own home country (e.g. study by Kruyger and Laitin in Terrorism, Economic Development, and Political Openness. Eds. Philip Keefer and Norman Loayza. Cambridge University Press, 2008). This does not mean, however, that only Muslims and/or individuals motivated by religious doctrines or ideas become suicide bombers. Simplified narratives that misrepresent what the world looks like, equating suicide terror with religion, surface again and again and are unhelpful if we want to understand the root causes of such violence.

Interesting! Would be interesting, too, to see disaggregated data within the ‘intra-Muslim’ category. One would imagine that a high proportion of the observations in that group relates to Sunni-Shia tensions in Iraq? If so, what are the implications for the debate regarding the role of religion as a motivation?