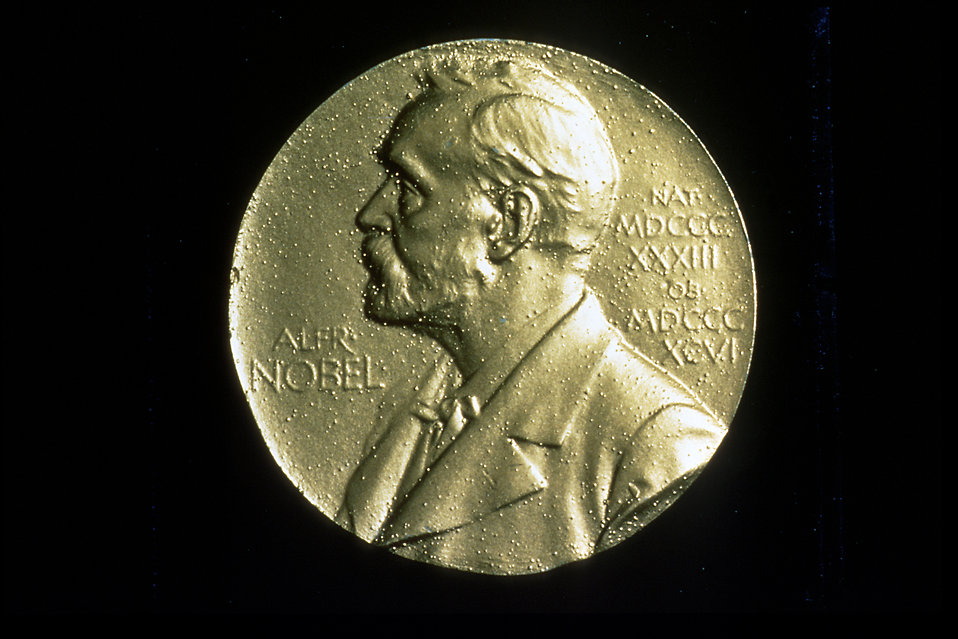

The award of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize is a bold choice. It rewards President Santos of Colombia for his great political courage, and for his ability to think in a strategic, long-term and principled manner about what is needed to bring peace to his country. Santos is also a “classic” choice for the prize. In his will, Alfred Nobel stated that the prize was for “champions of peace”, and many of the prize awards that we remember best have been awards to statesmen, rebel leaders or peace negotiators who have contributed to the ending of wars.

This year’s Peace Prize is a brave award to a brave politician. Juan Manuel Santos campaigned for the presidency with peace at the top of his manifesto, and he has thrown all his political weight behind this peace process. He is an experienced politician, and has always understood that many Colombians are sceptical to a peace deal. He has worked purposefully to include both FARC and civil society. Victims of the violence have been included systematically in consultations, and great weight has been attached to other considerations that are often forgotten in peace processes, such as the genuine involvement of women. The existent document is undoubtedly one of the most sophisticated peace agreements the world has ever seen, and it will come to be studied in detail by architects of peace in all corners of the world for a long time to come.

It is therefore understandable that many people were extremely disappointed over the result of the Colombian referendum on 2 October, when a majority rejected the current agreement. It is encouraging, though, that both Santos and FARC have expressed willingness to continue negotiations, and voters on the “no” side are also insistent that they want peace – just not in the form agreed between Santos and FARC. But in light of the referendum, which torpedoed Santos’s peace agreement with FARC, it will be interesting to see how the news of the peace prize will be received in Colombia, particularly by the “no” side – headed by Santos’s predecessor and rival Álvaro Uribe.

Colombian politics is characterized by polarization, and there is a risk that the peace prize may contribute to the feeling held by many that the country’s peace process is largely driven by forces that have everything but the welfare of ordinary Colombians as their goal. The Nobel Committee is well aware of this, and they have attempted to address this issue by emphasizing that this prize is being awarded not only to Santos, but to all who have contributed to the peace process, not least to all the victims who have been affected by the bloody civil war over the past decades.

The Nobel Committee has chosen not to include the FARC guerrilla movement or its leader, Timoleón Jiménez, in its award of the prize. It is easy to understand why the committee would resist awarding the prize to an organization that has made such extensive use of terror as a means to achieve its goals. But Santos has also stood for the widespread use of violence, both as president and in his time as defence minister. The government’s use of violence – and its collaboration with paramilitary groups – also violates basic principles of international law. A prize award that included FARC would have gone even further in rewarding people who have used violence and oppression, but it would also have rewarded the organization and its leaders for having committed to peace.

It appears that many of the people who voted against the peace agreement found it unacceptable that FARC’s leaders would be subject to relatively light punishments. The Nobel Committee explicitly acknowledge that there is tension between, on the one hand, allowing military leaders to put down their weapons, and, on the other hand, ensuring justice for victims. The prize comes at a time when FARC has been given a message that any peace deal in Colombia will require it to take greater responsibility for its actions. This will require considerable compromise on the part of the FARC guerrilla movement, and it is currently unclear what the government has to offer in return. If the FARC leaders also feel that they are not receiving recognition for the political will they have already shown, then this will be a problem.

Peace Processes back on the Table

The last time that the Nobel Peace Prize might be said to have been given to peace negotiations was in 2008, when Martti Ahtisaari was awarded the prize for his negotiating efforts in a number of peace processes over many decades. That time, however, the prize went to a peace negotiator – not to one of the parties to a conflict. The last time the prize was awarded to representatives of the parties to a conflict was in 1998, when the prize highlighted the peace process in Northern Ireland and was awarded to the two political leaders John Hume and David Trimble. That time the rebel group – the IRA – did not share the prize, just like this year’s prize did not include FARC. In 1994 the situation was different – that time the prize went to Yasser Arafat, Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin, for the Oslo accords between Israel and the Palestinians. Likewise, the year before, it went to South Africa’s Frederik Willem de Klerk and Nelson Mandela. Since then we have known that such awards are always controversial. Many are willing to accept even extensive use of force by governments, but protest movements that turn to violence are seen as more problematic.

The parties in Colombia have been clear that they will return to the negotiating table. Other supporting parties, such as the two countries – Cuba and Norway – that have helped in the negotiations, say the same. If one succeeds in ending the conflict in Colombia, then one will have ended the last armed conflict in Latin America, which for several decades has been characterized by wars and military coups. In fact, it will be the end of the only remaining conflict in the western hemisphere. If one links this achievement to a peace agreement that is outstanding in its thoroughness, and broad inclusiveness – not least of the victims – then this will be well worth a peace prize.

In this way the committee is returning to the essence of the peace prize: although this is a bold award, which expresses a strong desire to influence the course of history, it is also a “classic” prize, which goes to the heart of what the peace prize is about. Nobel Peace Prize awards have often been controversial – and this can be a good thing, as long as the controversy concerns a political ambition that is worthy of the Nobel Prize. This year’s award is “classic”, both because it aims to use the weigth of the prize to bring about a more peaceful world, and because it reflects the core intentions of Alfred Nobel when he wrote his will more than 120 years ago.