“I’ll be the first Palestinian woman to land on the moon,” she states with a wry smile.

The world – and space – lies at her feet, as in theory it does for children all over the world. But these particular legs are standing on shaky ground.

Palestinian girls. Photo: Ebba Tellander / PRIO

Her legs are in Lebanon, more specifically, they’re planted in a Palestinian refugee camp in the south of the small country. It was here she came into the world; here that these feet took their first faltering steps; in the narrow streets here that her legs have run around, learned to ride a bike, despite the neighbors’ many opinions about girls riding bikes; and it is here that these legs learned to shoot hard, dribble and bend the ball around the opponent, although the neighbors probably have opinions about that, too.

Her legs have grown tall here, her body about to become an adult. And its the same with her mind. She is the type of person who, in the face of something new, thinks, “I’m sure I can do this!” She also has a family that do all they can, so that she will have more opportunities than most girls in these parts. Still, the moon seems further away from here.

The reality is that, as a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon, her future is very limited. The Palestinians have been in the country since they fled the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948, and for as long Lebanon has hoped that they would disappear back to wherever they came from. While Israel has refused to let them return to their homes, Lebanon has refused to let them to establish new ones. For nearly seven decades they have lived here, most of them in camps that grow only vertically. It’s cramped here, and the space keeps shrinking. Less space for people, and less space for big dreams and free thoughts. There is no country in the world that has more refugees per capita than Lebanon right now. At the end of the street of our young astronauts house, a new mosque is being built by petro-dollars from the Gulf. I would not put my money on progressive, liberal Friday prayers flowing out of this new mosque. The Syrian battlefield is not the only place where the scrabble for regional influence takes place.

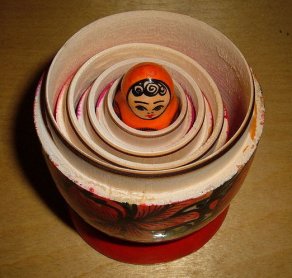

The Syrian crisis can feel like a Russian Matryoshka doll. Photo: BrokenSphere / Wikimedia Commons

If you stand in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, the Syrian crisis can feel like a Russian Matryoshka doll. Inside each doll another is nestled. Layers upon layers of crisis. The largest doll is the crisis that takes place inside Syria. It has long been bad in Aleppo, and yet it can still get worse. Food, medicine, and humanity are all scarce goods there. The Syria doll has almost no paint left; it’s just her face that has not yet worn away. When we take the top half off, we find a slightly smaller Lebanon doll inside. Paint has begun to flake here too. In some places it is already peeled off.

Already before hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees arrived, Lebanon suffered from both economic and political tensions. The Arab uprisings resulted in a decline in tourism and investments and an abrupt decline in the country’s economic growth. According to the World Bank, over 200,000 new Lebanese have been pushed into poverty as a consequence of the Syrian crisis in Lebanon. Many fear the domino effect from Syria, and many of us may have also been surprised that the situation has remained relatively stable, despite everything, for so long. But in the long term, can it still hold? Are the collective memories after years of bloody civil war enough to keep destructive forces at bay? Like so much else in the region, Lebanon’s future will likely also be linked to how things unfold in Syria.

When we open the Lebanon doll, we find one that is even smaller: Palestine. This doll often disappears, and it can be easy to forget that it is part of the set. But suddenly you’ll find it reappearing. The still unresolved Israeli-Palestinian conflict keeps generation upon generation of Palestinians as refugees. Hundreds of thousands have had Syria as their safe haven, until that country itself began to bleed refugees. Tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees from Syria have fled to Lebanon. The main impression one gets from talking to them, is that if there is something they regret, it is that they came here.

Because despite the fact that Lebanon has received well-deserved praise for taking in so many of Syrians fleeing, those who fled here find much to fault their hosts. Refugees’ rights are increasingly restricted and their legal situation is increasingly fragile. Getting legal residence in the country is expensive. It is often too expensive for the majority of the refugees, as their savings are often used up after years of soaring rents and idleness. Just as Lebanon has refused Palestinians to root for nearly 70 years, they refuse now Syrians. Life in these front-line states is certainly no picnic.

The acute humanitarian aid phase is gradually developing into longer-term development aid. This shift entails a major responsibility for the donor community, in making sure that states like Lebanon provides the refugees with more and better rights than what they currently have. Better rights and more opportunities must be a requirement, not only for the country’s “new” refugees, but also for those who have been there for decades. They need firmer ground under their feet, a stronger foundation to rely on, when they jump and reach for the moon.

- This text was posted in Norwegian in Dagsavisen 6 December 2016: “Månelanding“

- Translation from Norwegian: Amanda Cellini