Uncertainty concerning President Donald Trump’s China and North Korea policies have instilled new fears of war in East Asia, a region that has enjoyed a surprising level of peace for almost four decades. Yet, if China treats Trump with care, the region may remain peaceful.

Photo: Futureatlas

The Story of the East Asian Peace

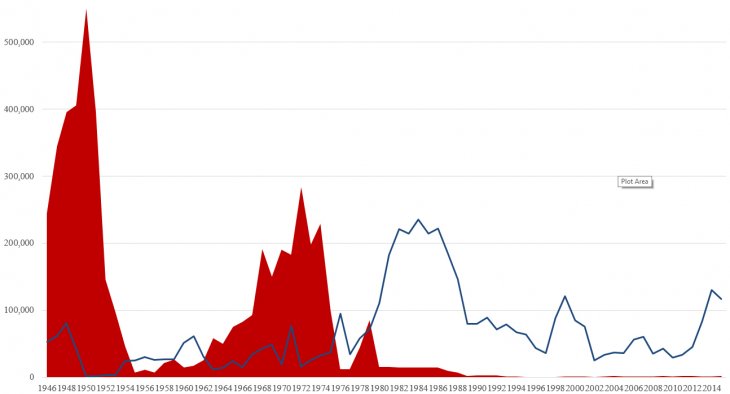

In order to assess the future of peace in East Asia we need to understand how it came about. As can be seen in the below graph, East Asia (Northeast and Southeast Asia) dominated world warfare in the period 1946–79, with 80 per cent of all the world’s battle related deaths. This was the period of the Chinese Civil War, the Korean War, the First and Second Indochina War (Vietnam War), and national liberation struggles mixed with civil war, in much of Southeast Asia.

The last war in the region was the Chinese invasion of Vietnam in 1979, following a Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia.

The graph uses PRIO Battle death data, 1946–2007, and Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) data, 2008–15. For those conflict years when the PRIO data have only low/high and no best estimates, the low estimate has been used.

In the 1980s, the East Asian share of global battle deaths dropped to just 6.2 per cent, although a low-intensity armed conflict cost thousands of lives in Cambodia. China and Vietnam exchanged artillery fire across their border until 1987, and small scale civil wars continued in several Southeast Asian countries. A serious Sino-Vietnamese incident occurred in the Spratly Island Group in March 1988. Then, in 1989, Vietnam withdrew its troops from Cambodia, and a peace agreement was signed in Paris 1991, which ended Indochina’s long cycle of wars.

Since then, East Asia has been remarkably peaceful, with only 1.7 percent of global battle deaths in the years 1990–2015.

The East Asian Peace, with no wars between states, and fewer and less intense internal armed conflicts than before, has seen a dramatic rise in the average life expectancy and the general standard of living in most of the region’s societies – and with modest improvement even in the countries that lag behind in the regional race for prosperity: Timor-Leste, Myanmar, and North Korea.

Deterrence, Dependence, Development

Some scholars see the peace among the great powers Russia, China, USA and Japan as anchored in nuclear deterrence, with the USA providing extended deterrence to Japan and South Korea. Yet nuclear deterrence did not prevent the wars of the Cold War period. It was the rapprochement between China and the USA in the 1970s, when President Richard Nixon visited China and Jimmy Carter shifted US diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China, that enabled East Asia’s peaceful development. Sino-US rapprochement put an end to the great power practice of supporting proxy armies in each other’s spheres of interest (Kreutz 2015). When the support was withdrawn, most ideologically motivated internal armed conflicts ended or died down.

The East Asian Peace went hand in hand with a rapid expansion of international trade and investments, stimulated by new information technologies, which made it possible for trans-national companies to manage global networks of production, with the final products being assembled in a low cost country from parts produced in multiple countries, and being sold throughout the world. This led to economic inter-dependence both within the East Asian region, across the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, and between the two sides of the Eurasian continent.

The East Asian Peace is not – as the European – a “democratic peace” since so many regional states are authoritarian. Some thus call it an “illiberal peace” (Kuhonta 2006). Yet is is liberal in the sense that it depends on open global markets, where private and state-owned companies compete. Some call it a “capitalist peace,” held up by economic inter-dependence. It has seemed possible that the combination of military deterrence and economic inter-dependence make war so costly for all of the major powers that they are constrained from allowing crises to escalate into war (Tønnesson 2015). Kivimäki (2014) and Tønnesson (2017a, 2017b) are not, however, convinced by either the deterrence or capitalist peace theses. They hold that the East Asian Peace is “developmental.”

Tønnesson’s peace story begins in Japan. Under US tutelage, its new leaders opted out of war in 1945–46 by adopting a peace constitution, forbidding their country from waging war or having an army, and concentrating on economic reconstruction and development instead.

In the following decades, one nation after the other followed the Japanese example by making economic development their top priority. The region’s main national leaders strove to achieve stability externally and internally, sometimes through coercion and repression, sometimes through diplomacy and the creation of legitimate institutions. It was essential for all the developmentalist governments to have a smooth relationship with the world’s leading economic and military power: the USA. South Korea, Indonesia, Singapore and Taiwan followed Japan’s lead in the 1960s, Malaysia and China in the 1970s–80s, Vietnam in the late 1980s. From the 1990s, Cambodia made progress as well, and now Myanmar is trying to catch up. Tønnesson (2017a), borrowing a political economy metaphor from Kaname Akamatsu (1962) calls them the “flying geese of peace.” East Asia’s developmental peace has been the cumulative effect of a number of national priority shifts.

In addition to the explanations based on power, economy and development priorities, there are also some cultural or ideational narratives: the peace has been shaped by an informal consensus culture based on respect for the principle of non-intervention, called “the ASEAN Way” (Acharya 2001, Kivimäki 2001; 2014); the peace is due to the traditional benevolence and modesty of Chinese culture (Kang 2007); it reflects China’s doctrine of “peaceful development” (Ren Xiao 2016); or it is due to an increasing interaction within regional confidence building networks (Weissmann 2012). The rivalry between these various theories has implications for how we see the risk of a regional return to active warfare.

Remaining Risks

Yet regardless of which theory has the greatest explanatory power, there is little doubt that the East Asian Peace is insecure. It does not build on the triangle of democracy, economic integration and international political co-operation (Russett and O’Neal 2001) that has characterized the European Peace – at least until recently.

Out of the three peace foundations, East Asia has just economic integration. And its pacifying effect may be lost if the Chinese economy – the main engine of regional and global economic growth – stops growing, if the volume of international trade is reduced even further, and notably if the USA – the traditional proponent of free trade – makes good of the shift to protectionist policies promised by Trump in his campaign.

Although Trump made friends with China’s President Xi Jinping when they met in Florida April 6th–7th 2017, the risk remains that the US will initiate a trade war against China, and use the unresolved conflicts over North Korea, Taiwan or the South China Sea as means to put pressure on Beijing. Some of Trump’s advisors have long argued that the US must put an end to China’s economic and military rise in order to maintain a US-led world order (Navarro 2015). Already under President Barack Obama, the US Army ordered a scenario study to be made of the coming US war with China (RAND 2016). Its main message was that China would suffer such huge losses that it would be wise to behave.

Another source of worry is the rise of assertive nationalism in many regional countries, not least China itself, with the result that there is acute tension between China and some of its neighbor states, notably Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines, although Manila made a pivot to China when Rodrigo Duterte became president in 2016. The mutual suspicion between the two strongest regional powers China and Japan provides both a major impediment to developing a more sustainable regional peace, and the main basis for maintaining a heavy US military presence, with a major base at Okinawa.

The Current Crisis

Trump’s anti-globalist “America First” policy presents Japan and China with dangers as well as opportunities. Some Chinese emphasize the latter: China should use its chance to take over the US role as a global leader, invite Australia, New Zealand, Latin America and a string of Asian neighbor states into a free trade area, form military alliances with Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines in order to make life more difficult for the US Navy, rely on nuclear deterrence to keep the USA off the brink, sell out of its US bonds and dollar assets, and accept huge losses of Trans-Atlantic trade (Yan Xuetong 2017). Xi Jinping, however, has chosen a more cautious approach. As long as the US policy remains uncertain, he does not want to rock any boats, and may even offer small concessions to the USA in order to prevent open conflict, such as imposing new sanctions against North Korea. This follows an established pattern. Whenever they have been uncertain as to the future course of US foreign policy, China’s leaders have refrained from testing the US resolve and have treated it with caution (Miura and Weiss 2017).

Xi Jinping has concentrated more power in his hands than any other Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, and aims to get his core leadership consecrated at the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th Congress in November 2017. In this situation, Xi is likely to look for ways to placate Trump and dissipate the threat of hostile US actions, while forging closer ties with as many other countries as possible, except perhaps Abe Shinzo’s Japan. Xi will also strive to keep his close strategic partnership with Vladimir Putin, but without emulating Russia’s propensity to use force abroad (Baev and Tønnesson 2017; Tønnesson and Baev 2017).

Xi Jinping seems keen to prevent a crisis in the Sino-US relationship. While he might go for a grand bargain concerning trade and investments, his current caution is more likely to produce just a respite in a difficult, drawn-out rivalry. Until a grand bargain is made, or the two governments have felt each other’s teeth in a serious crisis, we will have to live with the risk of a Sino-US confrontation. In 2015, East Asia suffered as little as 1.2 per cent of global battle deaths and in 2016 just 0.7 percent, although it has more than 30 per cent of the world’s population as well as of its GDP.

The statistics of the recent peaceful past, however, give no ground for complacency. Deterrence and inter-dependence may not be enough to safeguard the peace, if the region loses its faith in development.

- Read Nils Petter Gleditsch’s critical comments to the ideas outlined in this text.

- This text was first published in a Policy Brief by the think tank ThinkChina.dk.

- Listen to the PodCast Why Is East Asia so Peaceful? Can It Last?

- Watch the film East Asia’s Suprising Peace

References

Acharya, A (2011) Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia. London: Routledge.

Baev, P and S Tønnesson (2017) “The Troubled Russia-China Partnership as a Challenge to the East Asian Peace,” The Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences. doi:10.1007/s40647-017-0166-y

Kaname Akamatsu (1962) “A historical pattern of economic growth in developing countries,” Journal of Developing Economies 1(1): 3–25.

Kang, D (2007) China Rising. Peace, Power, and Order in East Asia. New York NY: Columbia University Press.

Kivimäki, T (2001) ‘The Long Peace of ASEAN,” Journal of Peace Research 38(1): 5–25.

Kivimäki T (2014) The Long Peace of East Asia. London: Ashgate.

Kreutz, J (2015) “Outsiders Matter: External Actors and the Decline of Armed Conflict in Southeast Asia,” Global Asia 10(4): 17–19.

Kuhonta, E M (2006) “Walking a Tightrope: Democracy versus Sovereignty in ASEAN’s Illiberal Peace,” Pacific Review 19(3): 337–358.

Miura, K and J C Weiss (2017) “Will China Test Trump? Lessons from Past Campaigns and Elections,” The Washington Quarterly 39(4): 7–26.

Navarro P (2015) Crouching Tiger. What China’s Militarism Means for the World. Amherst, NY: Prometheus.

RAND Corporation (Gombert, Cevallos & Garrafola) (2016) War with China: Thinking through the Unthinkable. Santa Monica CA: RAND.

Ren Xiao (2016) “Idea Change Matters: China’s Practices and the East Asian Peace.” Asian Perspective 40(2): 329–356.

Tønnesson S (2015) ‘Deterrence, interdependence, and Sino–US peace,’ International Area Studies Review 18(3): 297–311.

Tønnesson S (2017a) “Peace by Development.” In E Bjarnegård & J Kreutz, eds. Debating the East Asian Peace. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

Tønnesson S (2017b) Explaining the East Asian Peace. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

Tønnesson S and P Baev (2017) “Stress-test for Chinese restraint: China evaluates Russia’s use of force.” Strategic Analysis 41(2): 139–151.

Weissmann, Mikael (2012) The East Asian Peace: Conflict Prevention and Informal Peacebuilding. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Yan Xuetong (2017) “Trump era could help China boom.” The New York Times 26 January.