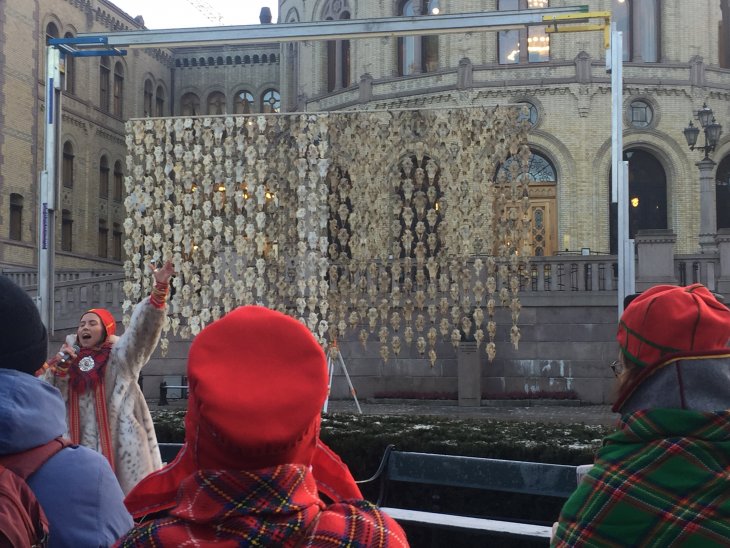

Protest outside Norwegian parliament to mark support for reindeer herder, Jovsset Ánte Sara. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Imagine this. Close to a small lake, there is a little building. It has stood there for 120 years – ever since your ancestors, who lived off fishing and foraging, built it. Your grandmother brings you to this place to pass your people’s traditions on to you. You go there in order to preserve knowledge, language, and cultural practices that have been passed down through generations, and that are at risk of being lost. Then one day, the state decides that this little, but important, building is built illegally. They set it on fire, and you have to see it burn to the ground.

In the beginning of April, the Swedish enforcement agency set fire to a Sami peat hut, and by doing so they set the blood boiling in many Sámi individuals, on both the Norwegian and the Swedish sides of Sápmi. There was a storm on social media, with posts marked with hashtags such as #colonialism and #ThereIsNoPostColonial.

This is not the first time Sámi activists have used the term “colonialism”. When the young Sámi reindeer herder Jovsset Ánte Sara met the Norwegian state in the Supreme Court in December last year, his sister, Máret Anne Sara, set up an artwork consisting of 400 reindeer skulls in front of the Norwegian parliament. The artwork was named Pile O´ Sápmi, and one of the slogans associated with it was exactly “There is no post-colonial”. In support of Sara, the Sámi artist Sofia Jannok performed in front of the parliament. During her performance, she did not hesitate to label Norway a colonial power. The president of the Sámi Parliament, Aili Keskitalo, has also been known to use the term “colonialism”. Last autumn, she called the plans for what could become Norway’s second largest wind park “green colonialism”.

The average Norwegian might see this as an example that identity politics has gone too far, that the language is being used out of proportion and that it should be sufficient to speak about respect for Sámi rights. We are used to thinking of colonialism as “the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically”. The relationship between the Norwegian state and the Sámi people does not seem to fit within this definition.

In principle, the process is the same: one state’s exploitation of the resources in territories that have traditionally belonged to another people, without their consent

But considering that under international law, indigenous peoples have special rights to land and natural resources that have traditionally been used by them, it becomes apparent that, in principle, the process is the same: one state’s exploitation of the resources in territories that have traditionally belonged to another people, without their consent. Therefore, from a Sámi perspective, the use of the term colonialism to describe the relationship between the Sámi people and the Nordic states is not that difficult to understand.

Sometimes it seems as if the Norwegian authorities lack both the willingness and the ability to familiarize themselves with Sámi perspectives. The Sámi Parliament is continuously ignored when it comes to questions regarding resource extraction and industrialization. Arguments in favour of creating employment opportunities and accruing wealth that will benefit the majority population are given more weight than Sámi rights.

Sámi traditional knowledge, cultures and languages are closely tied to the use of nature; losing the right to land and water could mean that we lose everything

Piece by piece, land is expropriated for new holiday cabins, roads, railways, mining and wind power, while local management of resources is replaced by stricter government control. It is not one single case, but the sum of all these cases that leads many of us to fear what future we will wake up to tomorrow. Sámi traditional knowledge, cultures and languages are closely tied to the use of nature; losing the right to land and water could mean that we lose everything.

It is not only Sámi activists that criticize the Norwegian authorities. Last month, the UN Human Rights Committee came with its concluding observations to the periodical report on Norway’s compliance with its obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Protecting and fulfilling the rights of indigenous peoples is one of the areas in which Norway has been asked to improve, for instance with regards to discrimination, lack of language training, and insufficient protection of Sámi rights to land, fishing and reindeer herding. The Committee expressed concern that the right to free, prior and informed consent, which is a fundamental principle for the fulfilment of other rights of indigenous people, is neither protected by law nor ensured in practice.

This shatters the image of Norway as a staunch protector of the rights of indigenous people. Norway may well be one of the best in its class, but that counts for little when the majority of the class is failing. So, to those that think the use of powerful words like “colonialism” might lead to more conflict and division, rather than dialogue and understanding, I say this: the conflicts are there already, it is only a matter of opening your eyes. Perhaps it is precisely this that the term “colonialism” can achieve.

- This op-ed was originally published in Norwegian in the newspaper Klassekampen on 11 May 2018: ‘Kolonistaten Norge’.