Inger Skjelsbæk, interviewed by Cindy Horst

Photo: PRIO

We focus a lot more on conflict than we do on what peace actually is. What is it that creates well-being? What is it that makes you feel at ease in your own skin, in your own life, in your own sociopolitical context? What does it take? All narratives about who you are and what your prospects are, and how that impacts your well-being, depend on how these stories are reinforced or challenged by the communities you live in. If peace is just the absence of war, then you have peace lots of places. But if peace is also well-being and resilience to conflicts, then it is more challenging.

I meet Inger Skjelsbæk at a café in central Oslo, early in the morning when things are still quiet and we can speak undisturbed. I have known Inger since I started working at PRIO more than a decade ago, and in that period, she has been my boss and I have been hers. An interesting fact about Inger is that she pretty much grew up with PRIO, being the daughter of former PRIO director and researcher Kjell Skjelsbæk.

Cindy Horst: What is it about you and your background that prepared you for being a peace researcher?

Inger Skjelsbæk: Obviously, knowing about PRIO was a part of my upbringing because my father worked at PRIO. I grew up with the PRIO logos on letterheads that were sitting around the house, and I remember being taken to PRIO as a young child with my dad. I can’t remember how old I was, and this is just an anecdote, but I remember there was a homeless guy who lived in the basement of the building where PRIO was in Tidemands gate 28 in the 1970s. I think my dad was going to pick up some papers on a weekend, and he took me along, and we met this guy as we entered. My dad had a conversation with him, and he needed some food, so we went in and got him a plate of food and gave it to him. Then my dad picked up his stuff and we went home. I just remember that it was exotic, you know.

I also remember some of the people who were working at PRIO when I was little – they used to come over for dinner. I remember Marek Thee and his wife, and that I was told that these were holocaust survivors, that their relatives had been killed. I just remember they were very nice to us kids, and how sorry I felt for them about their loss. I am not sure I fully understood the depth of their fate as a child, but that came to me later. The spirit of PRIO in a way came to me through those anecdotes and experiences, and conversations at home about what was going on in the world – those kinds of things primed me for wanting to do what I did. Being a PRIO child kind of primed me for becoming a PRIO person, I would guess. At least, it primed me for a specific kind of curiosity.

Left: Inger with her parents in Boston, 1970; Right: Inger with her father, Kjell Skjelsbæk, in 1970. Photo: private archives

But did you think a lot about this academic world and what it meant? Did you think of it as something you aspired to join or were you simply a part of it?

It’s not like I drifted into it; I took active choices. You know, growing up, I would see my dad on TV every now and then, commenting on political events. I remember him being on TV with Helga Hernes for instance, discussing nuclear disarmament. Those events made me proud and engaged and I wanted to learn more. I felt I was privileged because he could explain what was going on. I could get the background story without having to read up on everything on my own, and the world out there became part of the talk at home. Yeah, that engaged me.

As a teenager, I became more engaged myself in international affairs. I grew up in the Western part of Oslo and went to Berg secondary school (videregående skole), which in the 1980s was where Jonas Gahr Støre [later foreign minister and Labour Party leader] went as well, but he was older than me. It was a very active school. People were very politically engaged. Many people were members of political parties. I was never a member of a political party, but I had friends who were. I felt that complemented what I was used to from home. These were conversations that were easy for me to be a part of.

And when you say you were politically engaged, can you give some examples? What were you engaged in?

I had an interest in the world outside of Norway, more than party politics in Norway. I was an exchange student in 1986 with the American Field Service (AFS) in Quebec. That came from a wish to see the world. I didn’t want to go to the US – which many of my fellow students did – because I had lived there as a child. I therefore ended up going to Canada. I was so ignorant I didn’t even know they spoke French, so I realized: ‘Oh my God, I’m going to a French family’, and I went to a French, catholic girls’ school. That was a huge surprise for me, and a steep learning curve, since I had no previous knowledge of French or catholic girls’ schools. But through that learning experience, I was for the first time exposed to nationalist thinking and rhetoric. Not in a violent way, but I learned what it meant to be a French-speaking minority in an English-speaking majority setting.

I also got to know other AFS students from all over the world, so when I came home, I had friends in Venezuela, Sweden, Brazil and other places, who I stayed in touch with. Later on, I engaged very actively in AFS in Norway. I was a teacher for exchange students who came to Norway. I was a contact person for individuals who were here for a year – like a professional friend, if you like, in case something went wrong. So, this was my political engagement.

Then, when you finished secondary school, you had to pick what you were going to study?

I studied English and French, and then my father became very sick. We knew he was going to die, because he had a very severe cancer. At the same time, I had decided that I wanted to study psychology. I remember he said to me that in peace research, there is a need for people who study psychology. There aren’t that many people who study psychology who have a peace and conflict focus. So, when he died, that became kind of a thing for me: ‘Then I’ll do that’.

I wanted to go into peace research with a background in psychology. I studied at NTNU and at that time, Nils Petter Gleditsch had a part-time position at NTNU. This was just two or three years after my father died. So, I decided to contact Nils Petter because I knew of him, and I asked: ‘Do you think there is any chance I could be affiliated with PRIO?’, and he was really sweet, and he really encouraged me to apply. He told me about this student stipend that they had. I applied, and I was rejected.

I was thinking ‘this story has a happy ending’, but then you did not get it…

Exactly. The reason, I think, was that my thesis project wasn’t developed enough. I was too eager. But then I was encouraged to reapply, and I did, and then I got it. So, I came to PRIO in August 1995 and did my hovedfagthesis there. When that was done, I was offered the chance to be part of a project funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Affairs on gender, peace and security, which the MFA had initiated. After that, I just stayed because there were opportunities that came up. So it was Nils Petter actually, or it was my dad who said that this would be something valuable.

At that time in the mid-1990s, Malvern Lumsden was at PRIO. He was a psychologist. And Johan Galtung, he had written about psychology. There was a PRIO book from 1993 on the shelves, I remember, entitled Conflict and Social Psychology, edited by Knud S. Larsen. It’s not like psychology was a science that was absent from PRIO, but it was very minor. Now it’s more or less absent. Or very, very, very minor. I felt that there was room for that kind of knowledge, but it does not have a big place in the multidisciplinary field of peace research at PRIO or globally.

That seems like quite a big responsibility, the way you are describing it?

I came with that notion of bringing psychology – in the sense of the impact of war on individuals, that’s always been my focus – to PRIO. But, over the years that interest became transformed to a focus on gender and women. In my research, I have combined this dual focus – on gendered individuals. Understanding wars and conflicts is also a question of understanding individuals in cultures and sociopolitical contexts as opposed to only organizations and social groups.

So I felt that, as a psychologist, taking the individual as a starting point of analysis was important. I have been interested in focusing on such questions as: how do the changes that war and peace entail trickle down and impact the individual? My take has always been, let’s focus on individuals and see how they incorporate events, institutions, discourses – things that are out there – into their stories about who they are and who they have become, because of armed conflict. I felt that was an important perspective in peace research. I still feel that this focus on the individual is very important, and I feel sometimes that it is more marginal than studies on institutions, political systems, governance, and that sort of thing.

So, I guess you’ve always agreed with your father’s observation that a psychological perspective is important, and you’ve seen that this has been a good path for you as well.

Yes, and I have to say that I have always had support from the PRIO leadership, from Dan Smith to Stein Tønnesson and Kristian Berg Harpviken. I have never felt that I didn’t have a place, you know. I have just felt that I have not been part of the mainstream. However, there is a certain freedom in not being mainstream. I think it’s a good place not to be sometimes; it gives a degree of freedom.

I can see that. Can I ask if you have had any role models, both on a personal and an academic level?

No, not in the beginning, and this is related to not being in the mainstream. Maybe that’s one thing that I felt very strongly in the first maybe ten years that I was at PRIO, maybe even longer – that I didn’t have any role models. I felt that I was completely on my own. I saw other students who seemed to be lifted up by a senior researcher, and I didn’t feel like I had anyone like that. I felt that I had support in the sense that I had a place at PRIO, but I had to figure out my research path on my own.

But I was also lucky, because at the time the funding mechanism allowed for more ‘satellite research’ to flourish, more than it does now. I got funding from the Norwegian Research Council to do an exploratory study on sexual violence in war, and then for a PhD project where I was my own project leader as a very junior scholar. All the funding went to me, and I was completely independent. I mean I had my supervisor at NTNU for my PhD project, but I was given this possibility to develop a research niche of my own and I don’t think I could have developed as an academic in this field otherwise.

I had this strong interest in finding out more about how sexual violence in armed conflict impacts individuals and their communities, and no one had done this before, it seemed. I didn’t know what my research would lead to, and I didn’t know how big it would be, not my own research necessarily, but the focus on gender and war more broadly. I just knew I had this interest, and I had these sorts of academic tools that I could use to grapple with it. I was given the possibility financially and then also I got support from the PRIO leadership to do it, which was important. Today, I think it is much more difficult for younger scholars to develop something new in the way that I was able to.

Photo: Henne

But what about the NTNU supervisor?

If there ever was a good mentor, in my early days, it was her, Hjørdis Kaul. Yet she was no expert in the field of gender, peace and security. She was an expert in organizational psychology and had worked on women’s participation in work life in Norway. Therefore, it was the gender dimension that was her expertise. She was a very good conversation partner. Very supportive. She was there for many, many years for me.

I had this strong interest in finding out more about how sexual violence in armed conflict impacts individuals and their communities, and no one had done this before, it seemed. I didn’t know what my research would lead to

There were also people who appeared and supported me, like I remember Ingrid Eide. There was one episode, and I think this was when I was about to finish my thesis, so this would have been 1996. I remember I knew who she was, but I had so much respect for her and I felt that I could not approach her. It was a bit of a threshold for me, but then I decided that I should just go ahead and ask her about papers from the Beijing conference, the big women’s conference in 1995. So I called her and I remember the next morning I came to PRIO, and she had been there the evening before, after I had gone home for the day, and put a huge pile of documents on my desk with a very encouraging note saying, ‘Good luck, Inger’, and I just remember that it meant so much. Not just a pat on the shoulder. It was like, here are things you can work on. I felt I was being seen by someone with a PRIO standing, and that was very special.

Then I remember Cynthia Enloe, who is a very prominent scholar on women, peace and security. I wrote her a letter, also in 1995 or 1996, when I was trying to figure out what to do next, asking about research, you know the things that people now do over email and it takes no time. But I actually wrote a letter on paper, and then she wrote a letter back. I got a handwritten letter from her, which was also very encouraging, and she said, ‘I’m so happy that you want to do research on gender and conflict at PRIO’. She had worked with Dan [Smith, former PRIO director] in London before Dan came to PRIO. I think he was the one who said that I could write to her, but I was like: ‘I can’t simply write to her, are you crazy?’ But I did, and she responded. I keep that letter in my files and read it now and then. So yes, there were people who supported me, people you could admire, who responded, and who became sources of inspiration for me to pursue the research interests I had.

How has this balance been between the psychology side and the gender side? Have you felt that there was any tension?

I came in as a psychologist, and then I happened to work on gender issues. Then that identification changed, and I became much more of a gender researcher who also happened to be a psychologist. I think that comes with working in the institute sector in general, because you become much more topic oriented. Then your academic discipline vanishes a little.

Being in the margins can sometimes feel a little lonely, because you see that those who are in political science – with their literature, their terminology – have much more in common. It was as if they had a better match of topics and discipline than me. Even some of the same core terms I would know from psychology, but they meant something different for them. Sometimes that could be frustrating, but now I am happy that I have learned so much from different disciplines at PRIO. And I think in terms of increasing the understanding of the gender, peace and security nexus, it is good to have a wide range of disciplines involved in various studies.

And have you also through those years felt yourself to be a peace researcher?

Yeah, I think so.

The moment you started working at PRIO, that made you a peace researcher, or…?

No, I didn’t use that term about myself until … it was a bit like when I got married with my husband, you know, I said he was my boyfriend for about ten years, and then I said he was my husband. It was something that took time to get used to. I think it’s the same with PRIO.

I worked at PRIO, that’s what I would say, but would say that I was a psychologist. It was as if identifying as a peace researcher was a bit too big for me.

But now that I’m not at PRIO full time,[1] I say that I am a peace researcher, along with being a psychologist and gender researcher. I think the transition to becoming a peace researcher, for me, also came when others identified me as such. I mean that an identity can be reinforced by others. But I am not exactly sure what it means to be a peace researcher.

Inger Skjelsbæk giving a talk on sexual violence at NATO HQ in Brussels in 2013.

I was just going to ask you, what does it mean to you to…

…to be a peace researcher?

Yeah. It is something I am also curious about myself. What is that identity, or that group of people?

I think it’s an identification with a group of people. I gave a talk about this when PRIO turned 50. In the speech, I told a story about my dad. Because as a child I had to explain to others what my father was did. He was a peace researcher, and I had no idea what that meant. For instance, my best friend’s parents were doctors. That was much easier than having a father who was a peace researcher. So, in this speech I recounted, which is actually true, how I had asked my dad: ‘What am I going to say that you do? I don’t know’, and he told me I could say that he’s a kind of teacher, a kind of scientist, and a kind of helper. That of course didn’t fly very well when you were ten years old and tried to tell your friends in the schoolyard. The other parents were doctors or policemen or something else that everyone had heard of. My father’s job was a mystery. And my kids have suffered the same fate, having to explain to their friends what their mother does.

[A]s a child I had to explain to others what my father did. He was a peace researcher, and I had no idea what that meant. […] I had asked my dad: ‘What am I going to say that you do? I don’t know’, and he told me I could say that he’s a kind of teacher, a kind of scientist, and a kind of helper.

Yet my father’s explanation was quite good, I think; people have the expectation that a peace researcher is a particular form of scholar. They expect that you engage in promoting certain forms of change. I think that is a valuable expectation, and I think that we should deliver on it; be the helper, the scholar, and the teacher.

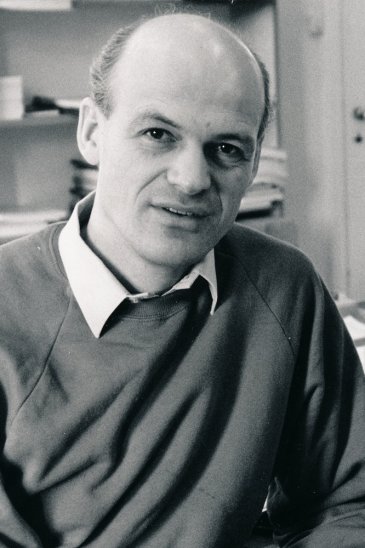

Inger’s father, Kjell Skjelsbæk. Photo: NTB

To me, I think the thing that makes PRIO a super interesting and valuable place to be is this generation of knowledge for a purpose other than just gaining knowledge and promoting your academic career. That has always been very important to me, and I think that’s important for most people at PRIO. It has come through in different ways, also in conversations among the PRIO leadership, when we have our discussions about research strategies. I think that is something unique to PRIO: it’s not just an academic job. It’s more than that.

What do you feel psychology would have to contribute to this?

I think that taking the individual as the starting point of analysis is valuable for understanding the impact of conflict. I remember I thought a lot about this when I was involved in PRIO’s dialogue projects in the Balkans. I was part of that for many years in the late 1990s and long into the 2000s. These were inter-ethnic dialogue meetings with people from all the former Yugoslav republics in collaboration with the Nansen Academy at Lillehammer. I thought that having expertise and knowledge in organizational psychology and group psychology, on how dialogues work, how negotiation works, was highly relevant. There is room there for psychological research, and that is not explored enough. Documenting and theorizing around the various forms of dialogue projects that PRIO was and is involved in could have been done much more than has been the case.

Ok, I would like to go more into PRIO questions. When we started, you talked about this ‘PRIO spirit’? Could you elaborate a little bit more on what that entails, starting with when you were a child?

Well, you know, that’s a big question. The PRIO that I heard about as a child and that I experienced as a child was an extended family. My mom will talk about this very affectionately. How they would have gatherings with the wives and the kids, and how they took care of each other. At times when my mom is not so affectionate, she talks about how everyone had equal pay and my father with this huge student loan and high education was paid the same as the cleaning lady, and they had lots of expenses. She was not so hippy happy about that, as my father might have been. But that of course is just like mythical stories that I’ve heard in my childhood.

The thing that makes PRIO a super interesting and valuable place to be is this generation of knowledge for a purpose other than just gaining knowledge and promoting your academic career […] it’s not just an academic job. It’s more than that

When I came in the mid-1990s, PRIO was a bit of a laidback place. There were lots of conscientious objectors and many more men than women. I also remember people wearing their slippers instead of shoes at work. So yes, it was a special place, I would say.

PRIO grew and became more professional and became a different place over the years that I have worked there. If I am going to summarize, it was international, it was communal, family oriented in the sense of feeling like an extended family, and it was quite male dominated. So, it’s changed a lot. But of course, I am romanticizing the past a little bit. But I have good and close friends from these early years at PRIO and I know that there are many other groups of ex-PRIOites who still meet and have maintained friendships based on work experience at PRIO.

I do not want to leave an impression that PRIO has changed in a bad way. It has just become much bigger and has a different dynamic. But now that I do not have my daily work there, I look at PRIO and think that it has a particular ‘PRIO spirit’, which is characterized by a strong sense of engagement and community.

But what about the international character? It sounds like it was very international. Has it become less so or is it still the same?

You have to remember I came to PRIO from Norway. Just working in a place where everyone speaks English was special. We had to speak English because when I came Dan Smith was the director and he was British. In addition, there was Robert B. Bathurst [the former US naval officer]. There were also Pavel Baev and Valery Tishkov from Russia and J. ‘Bayo Adekanye from Nigeria. So even though it wasn’t 50% non-Norwegians in terms of numbers, it felt very international in a Norwegian context. That, I think, is still the case. Then, in addition, everyone who worked there had lived elsewhere and was connected to the outside world, so to speak. I think this is also still the case. In terms of diversity, it’s still white and European and all of this, but by Norwegian standards it is international. A particular form of international, let’s say.

You were also talking about Marek. He was Polish?

He was Polish.

And this kind of presence of the older generation with actual holocaust experience, was that also part of the PRIO spirit to some extent?

You know what, I wish I could say yes, but I think that was probably more the case before I started. Because I know that from Ingrid [Eide] and Mari Holmboe Ruge, the experiences from the Second World War, and later from the Cold War, were of course very important. But for me it was the war in the Balkans that was the reference point. That’s why I started my research on sexual violence in war. I came to PRIO when the Bosnian war was ending. So the conflicts in the Balkans were “my” wars, if you like, my generation’s wars.

It comes into your living room, you see what is happening…

And you identify. The Second World War was present in the life story of Marek Thee and of some people I knew in my childhood. And I had a huge interest in the Second World War, I just read everything I could. But when I came to PRIO it felt as if it was more important to delve into the present, to try to understand contemporary conflicts. Even though the backdrop was always there.

So at that time, the Balkan war was for many people at PRIO a reference?

Yes. In 1994, the first groups of people from the Balkans were brought to Lillehammer. This was because Lillehammer was a friendship town with Sarajevo; the 1984 Olympic Winter Games had been organized in Sarajevo, and on the tenth anniversary in 1994 the Olympics were held in Lillehammer. At that time, I remember hearing stories from colleagues at PRIO, such as Wenche [Hauge] and others who went to Lillehammer to meet these people and talk to them. Then that started evolving and became the Nansen Dialogue Network that PRIO was involved with first through teaching, then through a more committed kind of leadership, and so on.

OK, now I would like to come to the gender dimensions, because it must be something quite particular.

I arrived at PRIO in 1995, and the Beijing World Conference on Women had just taken place. Norway wanted to follow up, and PRIO was contacted and asked if we could organize a large conference in Santo Domingo at the United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (INSTRAW). We went there and had a big conference on gender, peace and conflict. Dan Smith and I edited a book based on the conference, entitled Gender, Peace and Conflict, published by Sage in 2001.

This effort was funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with complementary funding from the Norwegian Research Council. This combined funding and research effort led to what later became the PRIO Centre on Gender, Peace and Security in 2015, through collaboration with Torunn Tryggestad. And then of course the big entrance of Helga Hernes, which is important. Going back, if I ever had any role model and a mentor it would be her.

Inger Skjelsbæk; Helga Hernes; and Torunn L. Tryggestad at PRIO in 2011. Photo: Hans Olav Myskja / PRIO

Why was it so important to have this big entry of Helga, why was that so crucial and what did it do?

Well, there were several things. First, she was senior and well respected. I was junior and just finishing my PhD, and you’re at that point where you’re thinking about what to do next. Then Torunn, whom I had collaborated with for many years while she was at NUPI, contacted me and said that Helga is retiring, but she would still like to be active. She encouraged me to contact Helga and ask her out for lunch. I was so nervous, because I had met her only a few times, but she seemed so stylish, and strict. Everything that I am not. I felt so junior and inexperienced around her. But I thought that I had to do this, and contacted her.

We had lunch, and I asked her if she wanted to come to PRIO, even though I had no mandate to do it. That was when Stein was director. I met him in the stairs in Fuglehauggata as I came back from that lunch and I asked: ‘Stein, is there any way we can make this work?’ Stein was, thankfully, very enthusiastic. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs was willing to provide funding for this work and Helga asked: ‘What do you think we should do with that?’, and Torunn wanted to do a PhD, so we were able to get her to come to PRIO to work on a PhD project on UNSCR 1352. So that’s what happened. Which was a huge change and a new turn for me. Not only did Helga come along, but also Torunn, who was my co-conspirator when it came to building up research on gender, peace and security in Norway.

We were talking earlier about being alone in the field of psychology at PRIO, but in the first 10 years that I was there, I was also pretty much alone in my research focus on gender, too. For many years, every little piece of information, mail, or phone call relating to gender would end up with me. It was as if they were thinking: ‘That goes to Inger. She is the woman person’. Then to have a group of three colleagues to have conversations with on a daily basis, and to have Helga who is so well respected and established, was fantastic. I am not a good political analyst. I am interested in people, but I am not good at analyzing political developments. I don’t have the vocabulary for it, I don’t have the training for it. Torunn and Helga are super at this. To be allowed into that company, and have them come to PRIO, was a huge privilege for me. It allowed us to manoeuvre funding, research, and engagement in ways that I had not been able to do before, and I have learned so much from them.

It also happened at a time when I had two little kids. Torunn also had two little kids, and we were exhausted all the time. Travelling was the last thing we wanted to do, but Helga could do that, and more. She could represent and make us visible on lots of different arenas. Therefore, she was such a blessing for both Torunn and myself. In addition, we grew much less fearful of her and are now very good and dear friends. And when I became deputy director at PRIO in 2009, Helga’s experience with leadership was so useful – I had lots of talks with her about various things. Then she was like a true mentor in the classical sense.

And the fact that you are a minority as a woman – at the start, did that matter at all? Now I guess we are more women than men at PRIO, but have you always felt that it doesn’t really matter if I’m a woman or a man, that you can interact on the same level?

In the beginning, I felt that there was a strong need to get more women at PRIO.

I think that now, at least with a comparative view from the University of Oslo, PRIO has done pretty well. It doesn’t mean that things are perfect. There are still things to do. But I think there is a place for conversations about gender dimensions in recruitment, assessments, and evaluations at PRIO that is open. I think that the gender research focus also has been part of that. Not that that’s the only reason, but the fact that it’s not just talking about women in various academic and leadership positions, but also gender dimensions in research.

I think that one of the things that I’m most proud of as a member of the PRIO community is that gender dimensions are part of many projects. You don’t have to be a gender researcher to have that focus. I think that by insisting on that, when funders also ask for it and PRIO has a capacity and willingness to respond, we enable reflections about internal dynamics at PRIO as well.

But over the years the number increased?

Yes, the numbers increased. Of course, that’s also a reflection of the fact that the number of women in academia increased in general. I talked a lot with Hilde Henriksen Waage, who was the deputy director during my formative years at PRIO. Female representation was something she cared a lot about. She had been here ten years longer than me, and she had felt that she was really one of the only women and felt that there were lots of issues to address. Because of her, and others, PRIO is now a much more gender equal place in terms of numbers and also in terms of research focus. That is something to be proud of, I think.

Alright, so we’ve talked about your personal story and PRIO, and I want to spend a little more time on peace, peace research, and the peace concept. Starting off with your personal connection or emotional connection to the concept of peace and even war: what does ‘peace’ mean to you?

Interesting. I have thought a lot about it lately. I was just at a conference entitled ‘Wars Don’t End’ at the University of Birmingham. The conference focused on many things relating to postwar, including children born of war, which is something I am developing a project on. Throughout the years that I’ve worked at PRIO, I think Johan Galtung might be right – we focus a lot more on conflict than we do on what peace is. And I think that psychological expertise could rectify some of that development. One important theme in psychology is the notion of well-being. What is it that creates well-being in people? What is it that makes you feel at ease in your own skin, in your own life, in your own sociopolitical context? What does it take? I think we have focused way too little on what that means. I think that’s relevant for peace research and for the notion of peace.

I have also thought about this in relation to transitional justice: the notion that justice is needed for reconciliation to take form and for peace to be established. When you think of peace in terms of justice, the people who are involved think in terms of their rights. If your rights aren’t met, then the justice has a counterproductive effect, because then you get upset and risk installing a sense of new violations, i.e. violations of rights. I would love to see more academic thinking and more research on what it is that makes people feel that they have a life in peace, feel like they have well-being, feel that they have developed resilience against conflicts. I think that maybe political science is not the academic discipline with the greatest capacity to do that kind of research, but there are other fields that would be more appropriate for developing that kind of knowledge, like anthropology, community psychology, philosophy, and sociology, and I think that’s really needed. If peace is just the absence of war, then you have peace in lots of places. But if peace is also well-being and resilience to conflicts, then it’s a different kind of work and research.

How does the individual and the collective come into that? Because if you think about well-being, that also has a lot to do with one’s own being at ease with oneself and everything, whereas in peace and conflict, it’s always about relations between people?

I am thinking about well-being in the sense of a community approach. Well-being obviously is something about being at ease with yourself, but you can’t have a society with individual therapy for everyone who has been in conflict. So, you need to think in terms of the community level.

I would love to see more research on what it is that makes people feel that they have a life in peace, feel like they have well-being, feel that they have developed resilience against conflicts.

I think all narratives about who you are and what your future prospects are, and how that impacts your well-being, are dependent on how these stories are reinforced or challenged by the communities you live in. And there you can do something, you know! Just going back to the work that I’ve done on survivors of sexual violence: they can get a lot of individual therapy and help, but if the society constantly stigmatizes them, then it’s very hard to maintain a notion of yourself as a survivor, as someone who has agency and control over her – or his – life. You need to be reinforced by the larger society in your understanding that you were a victim of armed violence in a conflict setting, and that you were not yourself at fault. If you are recognized as an innocent victim, you do not need to feel stigmatized. That conflict-related story must be reinforced on the level of the community and society.

Kim Thuy Seelinger (Director of the Sexual Violence Program at the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley); Denis Mukwege (Nobel laureate); Inger Skjelsbæk; and Pramila Patten (Special Representative of the UN Secretary General on Sexual Violence) at the Nobel Banquet in 2018. Photo: Private archives

I find it very interesting that you bring in narratives and stories, so it is also about the stories you’re able to tell about yourself and the visions of the future you can imagine. About how it is that these stories are created, and how people create their own story in a way that supports well-being and a sense of peace.

In a way of course, as researchers, we contribute to this; I don’t want to say that researchers do storytelling, but they contribute to the societal stories about peace and conflict. What if, for example, PRIO doesn’t create these stories about what peace really is, and instead creates a lot of stories about what war is about?

I think PRIO has in its mission statement – there is a formulation, isn’t there? – I think it says that PRIO ‘conducts research on the conditions for peaceful relations between states, groups and people’. But ‘peace’ is a concept that comes with a lot of baggage. It can be very hard to engage with and maybe conflict is an easier term to engage with.

Because peace comes with a whole baggage of activism, or…?

Yeah, it comes with a notion of activism, religiosity, and more. Of course, for that reason it’s important that PRIO defines what it means in a PRIO context. And I think in a way we have done that, in the mission statement. But of course, PRIO is not completely free to simply decide what we want to do when we do peace research. Because research has to get funded. If funders are much more interested in research on how to end conflicts, that’s what you’re going to talk about and that’s how it has to be. But, perhaps mapping out in more detail what these conditions for peaceful relations might be could be a reinforced focus at PRIO in the next 10 years?

What you’re saying is that you can’t really have sustainable peace by just focusing on conflict. You really need to understand what that ideal peace is all about. Which is I guess also going back to Galtung.

Yes, I sound like a Galtung follower, but my reference point is also obviously what I’ve done myself in terms of gender dimensions. Just to take one example, if you think about narratives about war and peace, and the gender relevance in that landscape, then wars change gender relations and dynamics, often profoundly.

Elise Barth, a former PRIOite, wrote a report many years ago called ‘Peace as Disappointment’, about the experiences of Eritrean female fighters, because their imagined peace was based on idealized notions of the past, of what they thought had been before the war. It was not based on the reality of what was before the war, but on idealized memories. In that context, often after a conflict you will see a turn to extremely rigid gender roles because extremely rigid gender roles somehow represent a form of security, something recognizable after upheaval and turmoil. Peace, therefore, may not always be the best thing for women. What kind of space is created after a conflict for different people? And what stories are they offered about who they are and were, and who they should be in the future?

To me, it is super interesting that peace is not always good, or that it can be many, many different things. Peace can bring new restrictions for women. It can give less security. (After the Vietnam War, for instance, the Vietnamese male fighters were rewarded with official leadership positions in the postwar society, although they were much less competent than the women who had filled those positions during the time when the men were out fighting). Very often, the end of a war gives women less security. This is one reason why they sometimes want to continue to carry arms. Arms make them feel secure in an insecure setting. These dimensions must be studied more.

Often after a conflict you will see a turn to extremely rigid gender roles because [they] somehow represent a form of security, something recognizable after upheaval and turmoil. Peace, therefore, may not always be the best thing for women. What kind of space is created after a conflict for different people? And what stories are they offered about who they are and were, and who they should be in the future?

I just want to end with your quote from your father when he was trying to explain what he was doing. A peace researcher is a teacher, helper, and scientist. For you, thinking about peace and the work you have been doing, how do these three elements come in?

Very concretely, actually. First, the scientist: when I came to PRIO in 1995 the Bosnian war was ending. I had an interest in women’s experiences. I had written my thesis about women’s narratives of war in different conflicts. I saw all these reports about sexual violence in Bosnia and found that little academic work had been done about it. I literally went through books in the PRIO library and looked for research on sexual violence in war only to find that there was hardly anything on women and nothing on rape. So, part of my motivation for doing research on sexual violence in war was a wish to make this subject scientific or bring those experiences into scholarly discussions about armed conflict. The question was, how is rape effective as a weapon of war? If it is a weapon of war, what does it do? How does it destroy people, or opponents? So that was very concretely my motivation for doing that research.

Then, teaching: I think I’ve said yes to almost all the requests I’ve received to talk about this in various settings. I’ve been to NATO headquarters and talked about it, I’ve talked to military students in Norway, I’ve talked to NGOs. Bringing this knowledge to the users was a big thing.

Then the helper part, how does this help people? That’s harder. I’ve interviewed survivors and people affected in various ways, but I’m not going to claim that by talking to them and asking them questions I have helped them in any way. Yet I think and hope in the larger picture of things that the fact that their experiences have been recognized by the efforts of mine and my colleagues carries some importance for them.

Knowing that I have helped organizations in Bosnia to get funding for their work also counts. That’s been something. Not that I’ve raised a lot of funds, but I have helped with some events and things. In addition, I think that the Missing Peace Initiative, which was a collaboration between the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley, and Women In International Security (WIIS), has been one way of ‘helping’, in the sense of making knowledge available to concerned users and other stakeholders. We organized meetings with policy makers, practitioners, and researchers.

But is that a difficult balance also? I mean, you are an academic, so you’re not supposed to be an activist, I guess.

I don’t feel that as a problem. I feel that as an academic, sometimes I just need to take a phone call to put people together, saying that I’ve interviewed these people. This is what I’ve done. Interviewed people in Bosnia, been in contact with people, and then in contact with the Norwegian embassy and I have suggested: ‘If you don’t know about these women doing this great work, maybe you could talk to each other?’ It’s just facilitating I would say, more than being an activist as such. I have been asked sometimes to do more activist work, and that I’m not comfortable with. But being a facilitator, that I’m fine with.

But I think for many it doesn’t tally with the role as an academic.

That may be true. But there are ways of combining. For instance, the work that Torunn has done – that I’ve been part of in the margins – with the Nordic Women Mediators (NWM) network. That involves a big teaching and helping component, in the sense of generating knowledge and putting it to use. Making sure that people who work with peace and reconciliation have tools with which to address the gender dimensions of that work. Now we’re working with the UN to provide academic input for their work on sexual violence in armed conflict and what kind of knowledge they would need.

Torunn L. Tryggestad; Helga Hernes; and Inger Skjelsbæk at the launch of the Nordic Women Mediators (NWM) network in 2015. Photo: Julie Lunde Lillesaeter / PRIO

This kind of work is, I think, extremely meaningful, and PRIO is excellent at doing this kind of work, which is why I really want to stay affiliated with PRIO for as long as I can. To be part of those kinds of efforts. I don’t think that every person at PRIO should necessarily work in such a way – that is, balancing research, teaching, and engagement at all times. But I do think that PRIO as a collective should continue to work in this way, facilitating the generation and transfer of knowledge amongst a range of users. I think the possibility of having an impact, and being the helper, and making knowledge come to use is and should be a big part of PRIO’s identity. I think it is, and I hope that never goes away.

Thank you very much, Inger.