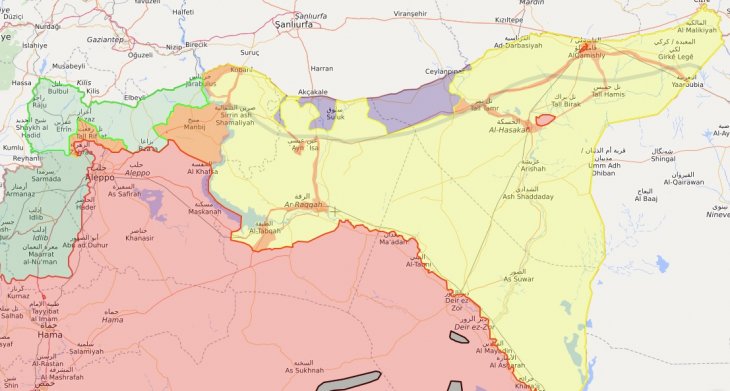

On 9 October 2019, Turkey launched its third invasion in Syria dubbed “Operation Peace Spring”, this time in north-eastern Syria. The previous two operations, “Euphrates Shield” and “Olive Branch” took place in north-western Syria (west of river Euphrates) and established a Turkey-controlled zone between the cities of Jarablus to the East and Afrin/Efrin to the West (see map below).

Operation Peace Spring started with artillery and aerial bombings by the Turkish military and expanded later to a ground advancement by Turkey-backed Syrian anti-regime forces of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and Syrian National Army (SNA). The operation came right after US President Donald Trump had announced that US forces will withdraw from the Turkish-Syrian border in north-eastern Syria due to an imminent Turkish intervention.

Yellow: Kurdish controlled territories. Red: Syria government controlled territories. Orange: Territories returned to the Syrian government after an agreement. Purple: Territories controlled by Operation Peace Spring. Light green: Turkey controlled zone West of Euphrates. Dark green: HTS (Syrian al Qaeda) dominated territories. Source: https://syria.liveuamap.com/

A “Safe Zone” and New Spheres of Influence

The declared objective of Turkey’s operation was the creation of a “safe zone” along the Turkish-Syrian border in north-eastern Syria by pushing back the Kurdish YPG (People’s Protection Units) which Ankara considers to be a branch of the Kurdish separatist organization PKK in Turkey. Despite Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s rhetoric, the ground operation showed that the tactical objective was more limited and focused on a territorial zone around 120 km long, extending from Tal Abyad at the western end to Ras al-Ayn at the eastern end, and around 20–30 kilometers wide.

Faced with the superior military machine of Turkey, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, led militarily by the YPG) came to an agreement with the Syrian government that entailed the ceding of Kurdish-controlled territories back to the Syrian government in return for security against the Turkish intervention. Thus, Assad’s Syrian Arab Army (SAA) has entered territories such as Tel Rifaat, Manbij, Raqqa, Kobani, Hasaka and Qamishli. As such, the territories controlled by Syria’s government expanded and with them the Russian and Iranian spheres of influence as well. At the same time, the US sphere of influence, which is largely based on Kurdish proxies, shrunk.

Turkey continued its operation and has not practically threatened any of the locations under Syrian control. Amidst the fighting, the US and Turkey reached an agreement that would pause Operation Peace Spring for 120 hours in order for Turkey to establish a “safe zone” from which the YPG would withdraw.

The agreement essentially gave Ankara what it has been pursuing for a long time. Certainly, Turkey is not able to reinforce the safe zone along the full length of the border since many areas are now controlled by the Syrian government. Even so, Turkey is content with the result as one of its main strategic objectives has for the time being been achieved: the YPG will withdraw from the border further to the south and/or be stripped of the control of any border towns and cities.

On the diplomatic level, it seems that the US is attempting a rapprochement with Turkey that would bring it back closer to the Western camp and ideally push it away from Russia. At the same time, it looks like Washington is trying to convince the Kurds to compromise the size of their territories in exchange for a potential political role in the new constitutional order that will emerge in Syria.

In any case, the Syria conflict cannot be comprehensively settled without the agreement of the Syrian government, Russia and even Iran. Therefore, the meeting between Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Russia on 22 October is believed to be critical for the way ahead.

A likely scenario that has been floating around is the possibility of a new agreement between Turkey and Syria (with mediation from Moscow) akin to the Turkey-Syria Adana Agreement of 1998. In a nutshell, such an agreement would entail that the PKK-YPG would not be supported by the Syrian government and that the latter would make sure that these organizations have no control over border territories. At the same time, it would allow Turkey to enter Syrian territories for minor military operations in the case of a PKK-YPG threat.

The Islamic State, and Human and International Security

Among the complex geopolitical dynamics, both at the military and diplomatic level, another and more asymmetrical security challenge arises: what will be the fate of Daesh- (ISIS/ISIL) affiliated individuals? This includes both ex-fighters and their families who were displaced from the territories of the self-proclaimed Islamic Caliphate (2014–2017) and were kept by the SDF.

When Operation Peace Spring was launched, the Deir ez-Zor campaign against ISIS by the SDF was practically still ongoing. As of March 2019, a combined task force of US special troops under the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF–OIR) command and Kurdish forces (SDF/YPG) were fighting in areas of eastern Syria against some of the remaining cells of ISIS.

Since the beginning of the operations against ISIS, the so-called Caliphate has collapsed, leaving behind an estimated population of 74,000 people related to the extremist organization. Most of these people (i.e. non-combatants) have been transferred to a refugee camp in the outskirts of al-Hol town in northern Syria. The battle of Baghuz Fawqani (the third phase of the Deir ez-Zor campaign) took place around the middle of the Euphrates River Valley and was the final step in pushing ISIS further to the east, resulting in its collapse. Only some cells of fighters remain active within a limited territorial space near the Iraq-Syria borders.

As a result of the operation, almost 9,000 ISIS fighters (plus 2,000 foreign ISIS fighters) were taken as prisoners of war by the US and SDF forces. Among them, there are some battle-proven veterans that were transferred, immediately, to the Ayn Issa camp – between Tal Abyad and Raqqa. More important ISIS figures are kept in Qamishli and in undisclosed US facilities.

Turkey’s involvement in north-eastern Syria created chaos in both the al-Hol and Ayn Issa camps. In the second case, 859 people, according to local sources, successfully escaped from the section of the facility that housed foreign nationals – a clear indicator that some very battle efficient ISIS veterans from third countries could be, in the near future, capable of creating a new insurgency situation or escaping to the jihadi-haven of Idlib in north-western Syria.

In the case of al-Hol, the fact that the majority of prisoners are women and children (around 20 thousand and 50 thousand respectively) – all relatives of fighters – creates serious conditions for a humanitarian crisis in the future, given the fluid situation and geopolitical complexities in the north-east among Turkey, Russia, the Kurds and the Syrian government. Further destabilization or conflict could trigger a new crisis resulting in dangerous conditions for the people in these camps and unaccompanied children.

What is more, the future livelihood of these populations – given that both the US and some EU member states insist on rejecting their repatriation – is at risk. Remaining in areas that will come under Assad’s control could create conditions for a new cycle of sectarian violence – especially if Shia armed militias (Assad proxies) deploy in the area.

If these populations seek refuge in Europe in the context of a new refugee crisis, European states and EU authorities will be faced with new and difficult security dilemmas. The EU should think about becoming more proactive in contributing to the alleviation of security challenges, not only at the humanitarian level but also at the diplomatic level, with the aim of reaching a political settlement to the conflict and bringing about a more stable geopolitical and constitutional order.

- Zenonas Tziarras is a researcher at the PRIO Cyprus Centre

- Ioannis-Sotirios Ioannou is the founder of Geopolitical Cyprus