With two special reports (which can be found here and here) released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) just after the summer, the awareness of the consequences of climate change and the measures needed to limit these impacts is higher than ever before. Regrettably, there is not a one-to-one relationship between responsibility and consequences, and the burden will be much larger for the already disadvantaged Global South.

Damaged coastal community in Iloilio province in the Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan hit the area in November 2013. Photo: Mans Unides/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

According to the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 45% of all natural disasters in 2018 happened in Asia and 15% in Africa. As the majority of these are climatological disasters, the international development community is increasingly making climate mitigation and adaptation strategies integral in their efforts to eradicate poverty. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) illustrate this, with goal number 13 explicitly being about combating the impacts of climate change.

The first target of SDG 13 is to “strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries”. Many of the countries that are most exposed to climate-related hazards have also been affected by armed conflict for decades. One example is the Philippines, where vulnerability to climatological extremes is enhanced by the presence of two armed intrastate conflicts. Together, conflict and extreme weather constitute key barriers to reaching the SDGs for the country.

SDG 13 specifically targets climate change and its impacts. Illustration: UN

In a recent study of disasters, conflict and aid project distribution across the Philippines, I find that development aid does not always reach those who need it the most. Rather, aid projects are more likely to be distributed to areas where the Philippine government enjoys popular support.

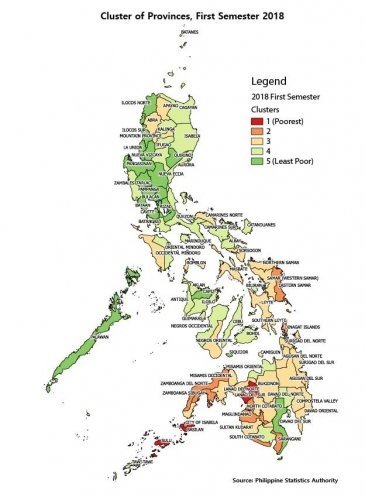

Although the idea that governments reward their own supporters is well established in the academic literature, the new study illustrates that ongoing conflict can be a significant barrier to climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. Even if the Philippines is one of the most dynamic economies in the East Asia and Pacific region, poverty and social inequality in the country remain rampant. These inequalities reflect the political divisions in the country. A map of the income distribution across Philippine provinces in early 2018 shows that the poorest areas are the southern islands, where the Mindanao conflict has been going on for decades.

Income distribution across the Philippines, first semester 2018. Illustration: Philippine Statistics Authority

Because the damage done by extreme weather depends on the vulnerability of the affected population, a same-magnitude typhoon hitting Mindanao will be potentially more deadly than one hitting Manila (in terms of monetary and material damages, however, the latter will likely be more costly). Building resilience and increasing the adaptive capacities towards disasters in these areas require long term development assistance, not just immediate disaster relief. Even if emergency relief aid is pivotal after a disaster, it generally does not contribute to improving an area’s resilience towards future disaster exposure. When some areas are (systematically) excluded from receiving development aid, they become trapped in a vicious circle where vulnerability to both conflict and disasters increases as the exposure continues.

In the above-mentioned study, I find that for the period 1996 to 2012, previous exposure to disasters did not increase the affected provinces’ likelihood of receiving new development aid projects from the World Bank. Provinces affected by armed conflict have a higher likelihood of receiving development aid, but only if the province is inhabited by a majority of the politically and socially dominant group, the Christian Filipinos. This means that the political bias permeates multilateral efforts towards sustainability, despite pronounced efforts at targeting the most vulnerable, including the people most severely affected by conflict and disasters.

It is important to keep in mind that these results are only true for aid that is channeled through the World Bank. However, the World Bank is perhaps the most central multilateral provider of overseas development aid (ODA) to the Philippines. Since the early 2000s, the Bank has oscillated between being the second and third largest donor to the Philippines, with a steady share of between 12 and 19 percent of the total ODA. Multilateral aid is generally thought to have less political bias than bilateral aid and be more attentive to recipient needs. This makes the findings even more discomforting.

The Philippine case illustrates how ongoing armed conflict can make societies more vulnerable and less able to cope with future climate extremes. It sheds light on the potential consequences of ongoing armed conflict for climate adaptation and resilience in exposed areas. It also underlines how important it for actors external to the conflict to make sure that aid projects reach the most vulnerable populations.

The study in question does not go beyond 2012, and we can hope that the increased focus from the IPCC and the new SDGs have resulted in the most vulnerable being targeted to a larger extent than they have historically been.

Elisabeth Rosvold is Doctoral Research at PRO. In her PhD project, she looks at how climatic disasters might affect ongoing conflict, aiming to uncover some of the mechanisms at play between disaster events and the dynamics of conflict.