Today’s post concludes our blog series marking International Open Access Week. In this blog, David J. Allen reflects on where we are in the transition to an open research system and who decides where we go from here.

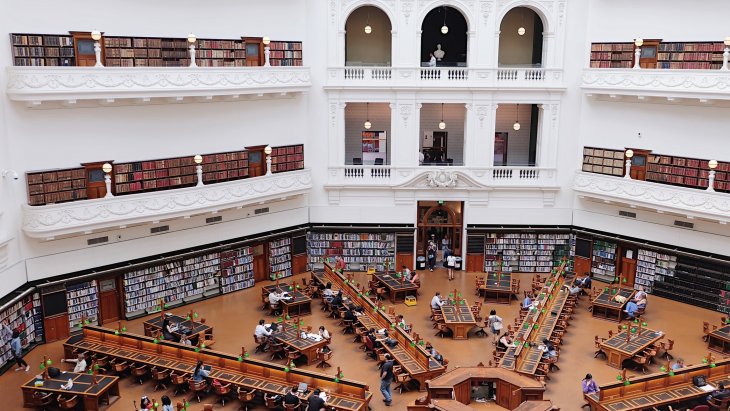

Photo: Geraldine Lewa CC via Unsplash

The compelling idea behind the push for open access is to fully integrate scholarly communication into digital culture. The exchange of ideas is at the heart of the scientific enterprise. The free flow of information made possible by the internet amplifies and accelerates this exchange. Open access, the thought goes, is a necessary condition for the creation of an ‘internet of the mind’.

However, digital culture isn’t what it was once thought to be. The OA movement matured in the ’90s and ’00s. In these heady days, the internet was going to provide the communicative infrastructure for a ‘global village’, a borderless knowledge commons. Today, we are faced with the fragmentation of the public sphere into a loose conglomeration of mutually hostile echo chambers and the capture of key facets of the fabric of our social lives by as yet unregulatable corporate special interests. This ageing vision of a knowledge commons is at risk of appearing quaint. Nevertheless, it’s an idea we should resist relinquishing.

At its best, science is an institutionalised social system subjecting the world and itself to continuous critical scrutiny. We need this system of scrutiny today more than ever, because we’ve become dependent on networks of communication that spread disinformation just as rapidly and indiscriminately as they do knowledge. Unfortunately, internet culture has also had a part to play in weakening the social standing of science. The democratising potential of the internet lies in lowering the barriers to participation in the public sphere. But this seems to have been concomitant with lowering the level of trust in ‘authoritative’ utterances, including those of researchers, experts and other ‘cognitive elites’.

I agree with Norwegian Minister of Research and Higher Education, Iselin Nybø, that open access has a role to play in rebuilding the flagging credibility of research and in facilitating the pushback by researchers against the global disinformation epidemic. However, access alone isn’t enough to build legitimacy. The rise of ‘fake news’ and the decline of faith in mainstream media, for example, has unfolded in a largely paywall-free environment. Beyond frictionless access to peer-reviewed research publications, a more holistic and nuanced approach to open research practices is the vital next step.

If there’s one thing we should learn from our ailing digital culture, it’s that technology isn’t a sufficient cause of openness. The internet is too malleable a tool to push behaviour in any one direction. Rather, we need to foster an open scientific culture, with transparency, inclusivity and involvement at its foundation. Digitalisation is a tool at the disposal of this culture, not its cause.

Equally, top-down mandates and policy declarations aren’t sufficient either. These can be significant tools for nudging researchers in one direction or another, but they are blunt instruments if the aim is culture change – and they lead reactionaries to dig their heels in as much as they enable innovators to create and argue for change. In order to succeed, the move towards a more open scientific culture needs to be researcher-led, even if this will inevitably mean a slower and more piecemeal transition than some might wish.

Ultimately, the key questions going forward will be: Who owns the knowledge commons? Who has the right to read? Who has the right to speak? Who benefits from opening research? These can seem like abstract, unwieldy questions, but how we answer them will have consequences for the nitty-gritty of the implementation of open science: Who benefits from funders disallowing ‘NC’ licences, and what are the implications of this for knowledge as a public good? How can scholars in the global south capture their fair share of the open science narrative and combat new forms of exclusion? Who should take responsibility for developing the infrastructure needed to run open science – researchers themselves, national state apparatuses, supranational institutions or for-profit companies?

Here at PRIO, we will continue to deliberate on these critical debates about the future of research – and to foster an inclusive and researcher-driven transition to a more open scientific culture.

David J. Allen is Adviser to the Director at PRIO. He has a background from scholarly publishing, having worked for a number of years with journals and open access at the Norwegian academic and higher education publisher, Universitetsforlaget.