Who are we accountable to when doing research on migration and mobility? Many scholars, ourselves included, do research with – rather than about – refugees and other migrants, or indeed communities and individuals in origin or destination country. But to whom are we accountable? And what can and should accountability entail in practice, in research ethical terms?

In the classroom. All photos: Marta Bivand Erdal

During the PhD course ‘Doing Migration Research Today’ at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, 30 October – 1 November 2019, we discussed practices of, and dilemmas related to, research ethics and research communication in relation to our research about refugees and other migrants, in contexts of origin, as well as destination or settlement. This blog post shares some of our reflections, as part of an ongoing conversation on research ethics in migration research practice. The blog post is co-written[1] by a group of us who were participating in the course and teaching it; building on the shared, interactive and ongoing nature of discussions about research ethics.

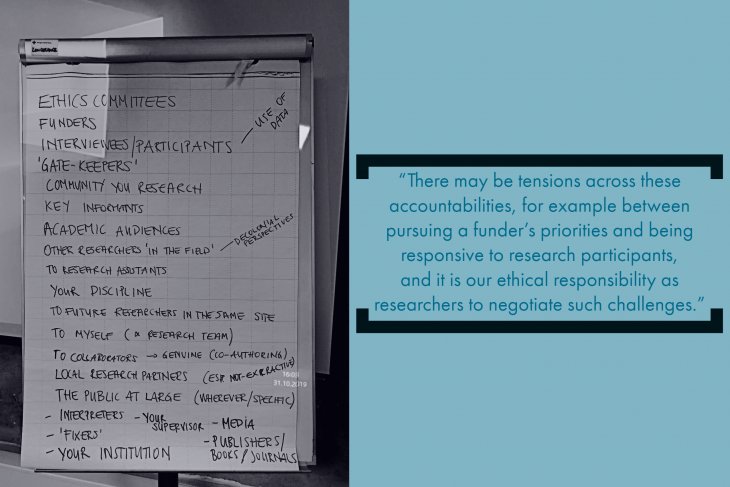

In an exercise, we brainstormed in order to identify the different actors and stakeholders to whom – in some sense – we considered ourselves to be accountable, in relation to our research. [See photo 1].

Photo 1: Brainstorming actors and stakeholders to whom we are accountable in our research.

Our list of those to whom we are accountable in our research – in one way or another – included:

The list was dynamically created, based on a roundtable brainstorm, and does not reflect any notions of hierarchies of accountability. Nor is it meant to be an exhaustive list. Rather, the different types of actors and stakeholders we listed may well overlap, and are in some cases nested, yet distinctive enough to be experienced by some of us as someone or something we are accountable to in our research practice. The bulk of actors and stakeholders are likely to be very recognizable, and as such the list will probably be relatable to many scholars of migration, and beyond. Yet our list, created during this session, would probably look different if created by a different set of migration researchers in another context.

There may be tensions across these accountabilities, for example between pursuing a funder’s priorities and being responsive to research participants, and it is our ethical responsibility as researchers to negotiate such challenges. Additionally, our individual positionalities as researchers influences how we deal with questions of accountability, from our relationship with research participants, to whom we cite, to how we want to present our work in the media.

As the list grew, it became clear that we were explicitly including the entirety of the research process: from idea inception, through planning and data collection, and also stressing the stages of analysis and writing. Research communication throughout the research process, not only as its culmination, was emphasized as a key dimension of how accountability matters in relation to a range of different stakeholders – from interviewees to publishers, though certainly not limited to these.

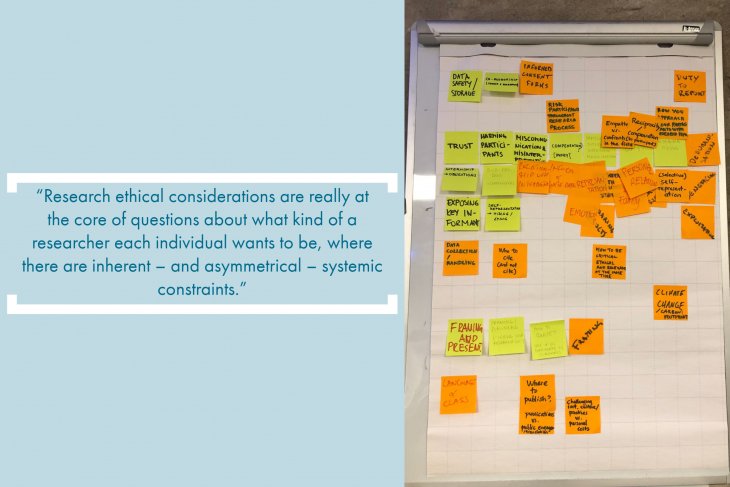

We then moved on to consider what might be the key research ethical concerns and dilemmas we specifically face when doing migration research, bearing in mind this wide range of actors and stakeholders to whom we feel a sense of accountability. [See photo 2].

Photo 2: Specific and pressing research ethical concerns.

In very practical terms, these were the research ethical considerations and dilemmas we listed, again neither is it an exhaustive list, nor one that prioritizes some issues over others. It is rather a result of a participatory discussion, with limited time at our disposal.

| Stakeholders | Concerns |

| Ethics committees, funders (and research participants) | Data safety & storage; Data collection & handling; Co-authorship (power and hierarchy); Informed consent forms; Duty to report |

| Interviewees and research participants & communities we do research within | Trust; Risk to participants; Miscommunication & Misinterpretation; Compensation; Gifts; Reciprocity; Representation; Empathy vs. confrontation in the field; Re-traumatizing; De-humanization; Exploitation; Added value of research (beyond “do no harm”) |

| Key informants | Exposing key informants |

| ‘Gate-keepers’ | Quid pro quo with gatekeepers; Internship obligations |

| Ourselves | Self-presentation (hiding/lying) |

| Interpreters | Relationship with interpreters |

| Academic audiences; Other researchers in the academic field; future researchers in the same research sites; publishers | Who to cite (and not cite); Framing and presentation; How to quote (research participants); Framing, publishing and “letting go” of your research; Where to publish; Challenging institutional culture/practices vs. at what personal costs |

| Co-authors | Power relations inherent to authorship and the importance of clarity regarding who contributes to the research process and in what ways. |

| The media; the public at large | How to be critical, ethical and relevant at the same time; Framing; Language & class; Academic publications vs. public engagement (and translation) |

An attempt at grouping ethical concerns to connect them to the issue of who we are accountable to revealed three things. First, it is not an easy task to place a specific research ethical dilemma of accountability squarely in relation to one specific stakeholder. At times there may be several different stakeholders, and at other times, there are inherent dilemmas and no clear-cut optimal solutions for ethical practice. Second, the single stakeholder group to whom most specific research ethical considerations were easily connected, was – perhaps rather predictably – interviewees and research participants. There was an array of quite different types of ethical considerations and dilemmas. Third, research ethical considerations are really at the core of questions about what kind of a researcher each individual wants to be, where there are inherent – and asymmetrical – systemic constraints, which also need to be recognized.

Our sharing of these reflections from our discussion, is intended primarily as an invitation to participate in an ongoing conversation about our responsibilities as researchers in terms of the ethics of accountability.

[1] Agata Maria Kochaniewicz; Akalya Atputharajah; Alexander Jung; Amanda Cellini; Ann Cathrin Corrales-Øverlid; Bircan Ciytak; Chaline Timmerarens; Cindy Horst; Eva Magdalena Stambøl; Ezgi Irgil; Francesca Soliman; Heidi Mogstad; Janina Pescinski; Magnus Skytterholm Egan; Marta Bivand Erdal; Masaya Llavaneras-Blanco; Nik Asif; Omar N Cham; Sarah Adeyinka (alphabetically by first name).