Entirely unprepared for what I was about to experience, I walked through the thick, dark curtain leading up to the main hallway of the War Childhood Museum. I had stepped into a different realm, one of physical objects telling stories of growing up in wartime. Each had a voice, some whispering and murmuring, others giving eloquent speeches, entering into dialogues with each other, forming choruses of defiant song, while others screamed in agonising pain. These diverse voices sounded deeply familiar as they echoed my own experience, yet also strangely distant as if my memories of war laid buried under layers of everyday concerns.

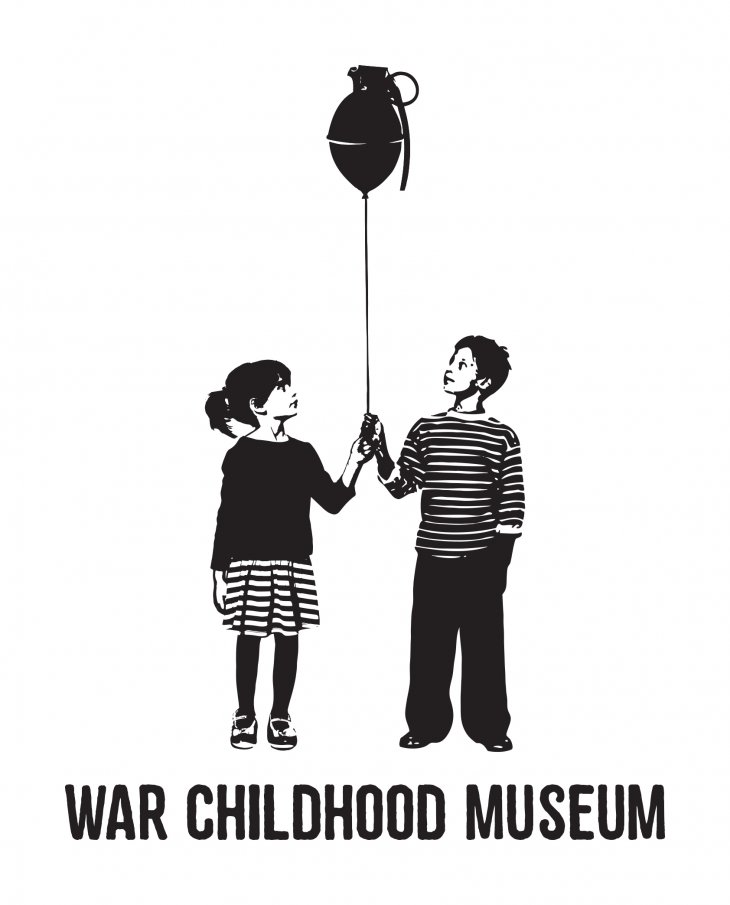

In an attempt to enliven his own remembrance of growing up under the military siege of Sarajevo, Jasminko Halilović posed one question to an entire generation: ‘What was war childhood for you?’ With the help of social media and other communication channels, the response he received was overwhelming. Over one thousand people, now in their late twenties, thirties and mid-forties – some living in the country, while many others dispersed around the world in Bosnia’s diaspora of two million – sent their brief replies.

They shared short stories, snippets, and snapshots, collectively piecing together an intimate view into the world of children experiencing war. Jasminko Halilović, the museum’s creator and founder, explains the process of compiling and editing the multitude of individual responses into a book and later permanently housing the collection of personal belongings and video testimonies in a museum. Each physical object is accompanied by an authentic story, imbuing it with meaning: helping it communicate a specific message and transfer a highly nuanced emotion. The storyteller is identified only by first name and year of birth, giving the viewer an approximate sense of his or her age during warfare. Over time, the museum’s exhibit expanded to include the wider experience of children in war, such as the current armed conflict in Syria.

Performing content analysis of the museum’s artefacts, Lejla Nikšić notes that, although the museum is not purposefully organised in either thematic or chronological sections, some clear emotional themes evolve from the individual storytelling. The theme of finding safety and refuge amidst displacement, uprooting, and loss of home is featured prominently and can be seen in ‘I was a refugee too’, ‘Keys to our house’, ‘My only fulfilled wish from 1992’, ‘Refugee identity card’, ‘My father’s perfume’, and ‘A friend’. These stories are characterised by the uniqueness of the child’s perspective, an apolitical stance allowing for personal identification reaching beyond any set religious, national, or ethnic boundaries and the universality of their message: central to notions of home and belonging is feeling safe and secure.

‘I was a refugee too’ and ‘Keys to our house’ both convey home expressed through physical objects, showing variety in approaches to home and its universal significance. The first – a suitcase filled with memories – represents the emotional home, while the second – an item directly related to the house – symbolises the physical home.

I WAS A REFUGEE TOO

They were already shooting on the city… One night, dad came home and said, ‘Tomorrow you are going to the seaside!’ I packed my suitcase: bathing suit, sandals, and diary. We are going to the seaside! In the morning my brother, mom, aunt, and I joined the convoy that was leaving the city. We are going to the seaside…Men in black masks stopped the convoy. They held us hostage for three days. Would I ever see the sea again? Two months later, I arrived in the Netherlands where I stayed to this day. All of my memories are in this suitcase. (Iva, 1981)

Theorists, such as Paolo Boccagni, posit feeling secure as the determining characteristic of home. The two objects, the suitcase and the keys to a house, both convey the same emotion of security. This emotion stands in stark contrast to the loss of home, caused by displacement or physical destruction. The storytelling accompanying the objects serves as an attempt to reclaim some agency in the process of recreating home.

Without challenging Michael Ignatieff’s perspective of ‘where you belong is where you are safe; and where you are safe is where you belong’, video testimonies of people directly narrating their wartime experiences insightfully question what safety actually means. Arma describes staying in besieged Sarajevo under sniper fire and finding safety through belonging to a community of people sharing the same experience.

KEYS TO OUR HOUSE

These are the keys to my house in Syria. I got them when I was five years old and I added some key chain ornaments to them. The keys opened the doors to the most beautiful house I had ever seen. My room had pink and green walls. Unfortunately, the house burned during the war so we don’t have a house anymore. When we left for Lebanon, I could not bring anything, because everything was completely burned. I took these keys, some toys that didn’t burn and some ash – the remains of our home. (Marwa, 2003)

There were many children from neighbouring buildings coming together in the cobblestone courtyard, which was somewhat protected from direct sniper fire by a tall building. In the beginning of the war, mostly adults gathered, because we had organised patrols in our neighbourhood. As time went by, everybody came together in that courtyard. It was filled with children of all ages, their parents, and all other neighbours. Some played chess, others made crepes. There was a stove and a fire there. We cooked together outside, even making plum jam and bread. We functioned as some kind of primordial community, where everybody takes care of everybody else. One mother would make sandwiches for all the children. We lived together in community, completely oriented towards each other. We played ordinary children’s games, hopscotch, hide-and-seek and many others. We even prepared a theatre performance. As time went by with colder weather our circle grew smaller. People were also leaving Sarajevo and we were becoming fewer in numbers. (Arma, 1978)

In contrast, Andrea’s story of refugee life abroad in peaceful conditions of apparent physical security points to her lack of belonging and consequently a lack in her own, subjectively perceived safety.

When we lived abroad, I missed my father the most. He stayed behind. Of our material possessions, we had nothing of our own. When we escaped Sarajevo, we could not take anything with us as we were not leaving our apartment. I remember the place we lived as refugees. In the beginning, I would not leave our apartment for months, just staring out of the window. One day, I finally collected the courage to go outside to play, hoping to meet some other children. When they saw me, the first thing they asked was where am I from? As soon as they found out, they would ask me questions like: ‘Do you know what a TV set looks like?’ This was horrible. I would break out crying and run back to the apartment. ‘Mom, do you have any photographs of our home? Do you have at least one photograph so that I can show them that we had a TV, a VCR, computer games and so much more?’ We had no pictures as proof and we constantly had to keep proving ourselves. What I missed most while living abroad as a refugee was the sense of belonging, of feeling safe. (Andrea, 1984)

Even twenty-five years after warfare has officially ended in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the question of who had a more arduous experience: those who stayed or those who left, is revisited frequently in acrimonious public discourse. Without proper context and empathy, these debates mostly lead to further fragmentation of an already deeply divided society. The voices of children, unafraid to embrace their vulnerability and speak their inner truth with authority and conviction add depth of understanding to this discourse. These voices underscore the general loss of decision-making capacities in times of war and unveil the fundamental human need to belong, to feel safe.

An aspect of the museum’s stated vision is ‘to help individuals overcome past traumatic experiences and prevent traumatisation of others’. I was seventeen when the war started in my native Sarajevo and I should be able to remember it well, yet when first walking into the dimly-lit exhibition space my recollections seemed oddly blurred. As I slowly walked by the artefacts, listening attentively to each tiny storyteller; as I cried and laughed watching the video testimonies, even recognising a dear friend and her late mother’s war cookbook, I could feel a warm sense of relief overpower my decades-long subconscious attempts at suppression. The experience of growing up in wartime is shared by an entire generation and in that realisation lies enormous potential for healing.

- Aida is a Global Fellow at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), Norway. Her research focuses on migration and diaspora studies, with a particular interest in how emotions relate to politics. She has a B.A. from Middlebury College, United States, an M.A. from Central European University, Hungary, and a Ph.D. in Political Science from Istanbul Bilgi University, Turkey.

- All photo credits: War Childhood Museum, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- This piece originally appeared in Routed Magazine online. You can find it here.

Everything is very open with a precise description of the issues.

It was truly informative. Your site is useful. Thank you for

sharing!