As the ongoing confrontation between the US and China has entered the technological and digital realms, we are pushed to rethink the relationship between individuals, nations and the entire world as more fluid than it has ever been before. While we grapple with these changes, the EU is on the right path ahead, but other countries are at risk of being left behind.

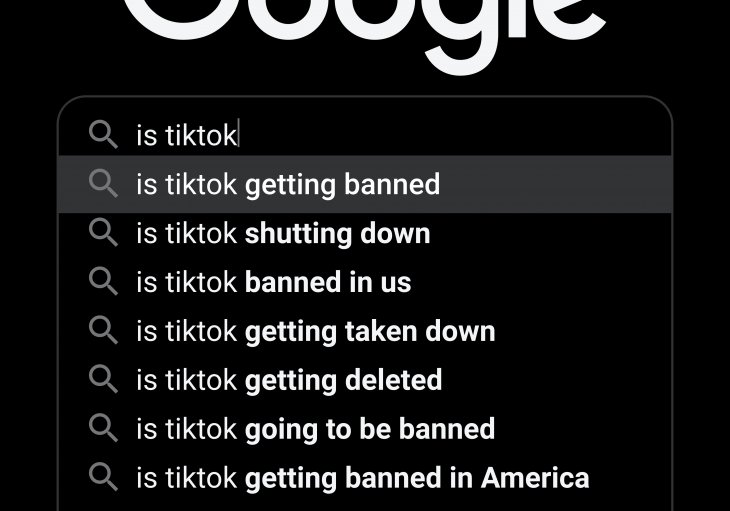

Recently, a number of Chinese-owned apps have been at the centre of media attention globally. As part of the ongoing China-US confrontation and in an attempt to counter China’s global influence, the US has embarked in what has been defined as a War on Data, actively trying to shut Chinese technology providers out of both US market and politics.

The main concern is that Chinese companies pose a national security threat if required to turn over users’ data to Beijing.

Generally speaking, free apps collect massive amounts of user data to sustain the business by offering ads, and the risk is that Chinese developers may use the data collection commonly used for advertising to train its national surveillance system. In the case of TikTok, for instance, the app was found logging what people were typing on their iPhones. While private businesses and governments in the West also collect personal data, when it comes to Chinese-owned technology, there are a number of issues that sets it apart.

Who owns our data?

First, it is an issue of scale. Facebook, YouTube, Samsung and Apple still lead the global social media and smartphone industry. But Chinese apps and handset makers trail right behind them: in 2019, WeChat had 1.1 billion users active users per month, immediately after Facebook (including Messenger), YouTube and WhatsApp; after Samsung and Apple, the next top phone makers globally are three Chinese companies (while different statistics present slightly different results, most seem to agree at least that Huawei was in the top three). Chinese companies have actively been targeting foreign markets that offer new opportunities to expand their user bases. Some have long made inroads in the developing world, such as Transsion, which sells more smartphones in Africa than both Apple and Samsung. They have achieved that by producing phones that directly respond to the needs of people in the continent, such as having multiple SIM slots, and cameras that are calibrated for darker skin tones, all at very affordable prices—much cheaper than their competitors. It is not a coincidence that many Chinese companies are now amongst the largest in the world; this is at least partly the result of a concerted effort from Beijing to promote Chinese businesses abroad and the government often offers financial and political support to both state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private businesses.

Second, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) does not just have informal influence over companies’ domestic and foreign operations: while companies such as Huawei, Tencent, and ByteDance are technically private, there are serious policy constraints within China that erode the boundaries between the private and the public.

The policy environment in China

For instance, in September this year, the CCP published yet another set of guidelines (in Chinese) that call on its members to “educate private businesspeople to weaponize their minds with [Xi’s] socialism ideology”. The document is titled “Opinions on Strengthening the United Front Work of the Private Economy in the New Era”. Essentially the deal with the private sector is, the CCP will help your business flourish (for instance with incentives and tax cuts), but your business needs to swear allegiance to the CCP.

This is only the latest of many iterations of several national laws in China that effectively remove any barrier between private companies and their user data and the Chinese authorities. By way of comparison, in the US companies like Google and Facebook can (and did) resist the authorities from accessing their phones and data. This is not possible in China, because the various national laws specifically prescribe for all companies, public and private, to cooperate with the government if so required. For instance, the national intelligence law from 2017 gives the CCP the power to monitor and investigate foreign and domestic individuals and institutions; Chinese intelligence agencies can search premises, seize property and mobilize individuals or organizations to carry out espionage; it also gives intelligence agencies legal ground to carry out their work both in and outside China; those violating the law will be subject to detention and can be criminally charged as well. These laws and the recent guidelines will therefore also make it more difficult for companies like Huawei, Tencent and ByteDance to argue that they operate independently from the CCP’s influence.

A similar example of policy constraint is the recently launched military-civil fusion strategy (in Chinese). Under this new policy, private companies in China that develop new technologies are mandated to share them with the Chinese government which will then incorporate them into military programs. This is part of President Xi Jinping’s goal to develop a world-class military by 2049, which marks 100 years since the Chinese Communist revolution. Introducing new technologies into weapons systems and military doctrine are therefore essential to the CCP, and one way to do it is by eliminating any remaining obstacles between China’s civilian and defense economies.

Privacy no more

It is against this background that I return to something I said in a recent episode of PRIO’s Peace in a Pod podcast, where I suggested that we need to think of these challenges on three, deeply inter-linked levels.

The individual right to be protected from external intrusion into our lives is something that many citizens hold dear, and especially in Europe this is considered sacrosanct (for instance, this belief is at the basis of the EU’s GDPR policy from 2018). While we are used to thinking of this basic level as very private and exclusive, the COVID-19 pandemic and the proliferation of tracking apps have, for one, questioned the boundaries between the private and the public. So, the second level—the national—is one where not only the nation-state but also us as citizens are confronted by a real threat, namely a foreign government acquiring sensitive information on its citizens; information that could be used for the purposes of political interference, to advance digital authoritarianism, or to achieve certain strategic goals. The blending of these two levels will require stronger trust between citizens and their governing institutions, as the data on our phones ceases to be inherently private and becomes part of a digital collective.

Finally, the third level is perhaps the most difficult to grasp, but it is one where digital sovereignty (or the absence of such) can have the most devastating consequences: if our own personal data, as well as the data of entire nations, is used to train artificial intelligence and mass surveillance systems that are used to discriminate against ethnic or religious groups, then we would indeed be entering the scariest of Orwellian futures.

These threats are real when it comes to Chinese-born technology and we cannot ignore them. However, it would be a mistake to label all things Chinese as automatically bad. In this sense, the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen recently took some steps in the right direction. During a virtual “summit” with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang, she and EU Council President Charles Michel went for a harder line with Beijing, particularly on issues such as trade, cyberattacks, and Hong Kong. While we are still far away from a coherent EU policy on China, EU countries should cooperate with China when possible, for instance on issues such as climate change and global health, while pushing back on issues such as the digital economy and research and innovation cooperation, including big data, technology and AI.

As we are busy doing that, we should not forget that if European countries ‘lose’ Huawei as a provider of 5G technology, they could afford another, if more expensive provider. The same cannot be said about developing countries in Africa and elsewhere, which are not in the same position. This is why developing digital and technological expertise and solutions made in Europe is so crucial—not only to solve problems at home, but also to offer better alternative to others.