The catastrophic levels of instability that have engulfed South Sudan since 2013 demand a restructuring of governance and security institutions to alter the tragic trajectory of Africa’s youngest state.

The Protection of Civilians (POC) site near Bentiu, in Unity State, South Sudan. Photo: JC McIlwaine / UN Photo

South Sudanese are observing the 10th anniversary of statehood with deeply mixed feelings. Children born during the post-independence period have seen nothing except misery and deprivation, with two out of five malnourished. Adults who hailed independence with excitement in 2011 are likely part of the 35 percent of the population that is displaced or count among the war’s death toll.

Large segments of the population are traumatized by the effects of war and demonstrate post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The freedom fighters and families of martyrs who saw South Sudan’s statehood as the ultimate prize of their selfless sacrifices, are likely to feel betrayed. Regrettably, 400,000 South Sudanese (a conservative estimate) could not celebrate, having lost their lives during the ongoing internal strife. Many in the international community and friends of South Sudan no doubt feel their goodwill has been squandered.

Despite these disappointments, many will be proud that they at least have a country of their own that they can fix one day will be proud that they at least have a country of their own that they can fix one day.

What Went Wrong?

South Sudanese, as well as their friends, continue to ask the fundamental question of what went wrong. Some scholars have said that South Sudan was a failed state before its birth, and therefore doomed to collapse. Others have attributed the failures to the tragedy of ethnic rivalry between the Dinka and Nuer. Yet, analysis shows that ethnic diversity need not be polarizing. Instead, much depends on how this is managed. Some ascribed it to a weak state structure and destructive dynamics of neopatrimonial governance. Examining South Sudan’s first 10 years through the lenses of governance and security provides some insight.

Governance Deficit

At its core, good governance is the effective management of the public sector in the interests of the general population guided by a national vision, constitution, and the rule of law. Prior to independence, South Sudan’s transitional government articulated a 2040 National Vision for the country:

By 2040, we aspire to build an exemplary nation: a nation that is educated and informed; prosperous, productive and innovative; compassionate and tolerant; free, just and peaceful; democratic and accountable; safe, secure and healthy; and united and proud.

Within this Vision, the government adopted a Development Plan (2011-2013) for the first 3 years of independence, with an overall objective:

To ensure that by 2014 South Sudan is a united and peaceful new nation, building strong foundations for good governance, economic prosperity and enhanced quality of life for all.

One of the pillars of this Development Plan is governance, which is aimed at strengthening institutions and improving transparency and accountability with the following objective:

To build a democratic, transparent, and accountable government, managed by a professional and committed public service, with an effective balance of power among the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government.

Since its independence, South Sudan has been ranked among the most fragile, corrupt, and conflict-affected countries in the world. Driving all these outcomes is that South Sudan has consistently been classified as “not free” and remains near the bottom of Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index.

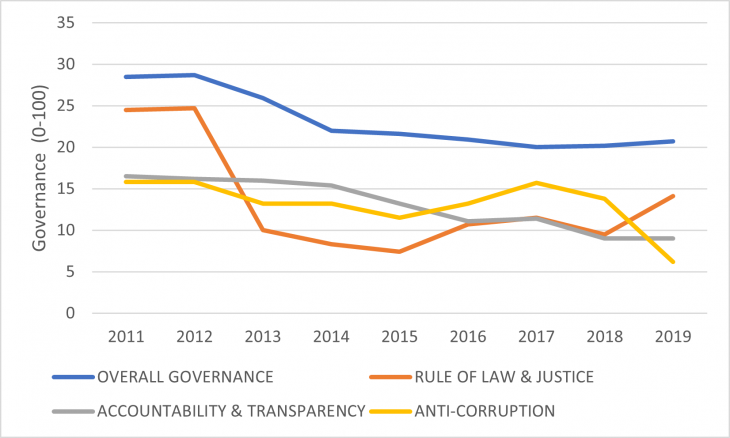

South Sudan’s governance measures are not only very low, but they are getting worse and are far below the average for the continent. The inevitable conclusion is that South Sudan’s post-independence leaders failed to live up to their commitments and the expectations of South Sudanese citizens. By 2014, the end date of the first 3-year Development Plan, South Sudan was not democratic as planned. Instead, it had regressed to an autocratic state that has thrust its people into abject poverty and abysmal living conditions. On its current path, there are few signs pointing to South Sudan becoming an accountable, transparent, and democratic government anytime soon.

Trends in South Sudan’s Governance. Source: Ibrahim Index of African Governance

Aside from the political choices that led to these outcomes, this governance deficit has been caused by structural flaws in the Constitution. The process of drafting the 2011 Transitional Constitution was regime-centered and exclusive, deviating from the aspirations and interests of citizens. This process produced a Constitution that lacked strong checks and balances and granted exclusive powers to the president. It also adopted a centralized unitary instead of a federal system, even though there was a strong popular preference for federalism. These flaws in the Constitution represented a faulty foundation for South Sudanese statehood that has led to the persistent governance deficit the country has faced.

Fractured and Predatory Security Sector

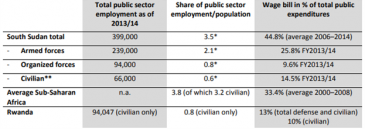

South Sudan entered statehood with vast resources (domestic and international) going to the security sector. This spending is colossal in relation to aggregate public sector employment and substantially higher than average spending in Sub-Saharan Africa. Besides this expansive spending, the security forces are comprised of antagonistic and unprofessional military factions. These factions are largely dominated by the two major ethnic groups with allegiance to their ethnic leaders instead of the state. This level of security spending has crowded out much-needed resources for other sectors such as health, education, and infrastructure.

Despite, or perhaps because of, this inordinate security spending, civil war broke out in 2013, less than 3 years after independence. Yet, levels of personal safety and national security had been declining even before then. Much of this threat comes from the security forces themselves. This predatory posture toward civilians was evident from before 2013, reflecting a focus more on self-enrichment rather than service to public.

Public Sector Employment and Wage Bill. Source: World Bank, 2015

This outcome also highlights the lack of a strategic framework for managing the security sector. This was demonstrated by the ineffective and rent-seeking implementation of the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) strategy pursued both during the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and the 2011 transition to statehood. This DDR strategy variously focused on ethnic packing and integrating rival armed groupsinto one “big tent,” regardless of qualifications, which undermined the ethos of a national army. It also, at times, forced certain communities to disarm while allowing neighboring communities to keep their arms, heightening vulnerability and perceptions of inequity.

Deteriorating Security Environment since Independence. Source: Ibrahim Index of African Governance

The fragmentation of the armed forces coupled with their loyalty to specific political leaders, a legacy of the independence struggle, allowed the new nation to be captured by a “gun class.” This failure to disentangle the politicization of the military and militarization of politics reduced the national security institutions of the new state into ethnically based militias. It also engrained mistrust within the security forces and set the new country on a path of recurrent violent conflict. Even with the requisite political will, this flawed composition and structure of the security sector makes reforms extremely difficult. This reality is manifested in the failure and resistance of the parties to the 2018 peace agreement to implement its security arrangements.

In sum, South Sudan has not been a peaceful or secure nation as articulated in the 2040 Vision. Nor are there signs that such trend will change in the term. This mismanagement of the security sector contributed to undermining the legitimacy and viability of the state of South Sudan and eroded the trust of citizens in the government.

Looking to the Future

As South Sudan’s political leaders signed onto the fragile 2018 peace agreement, the country faced three scenarios: status quo, statelessness, and stability. These remain relevant today, with status quo likely to prevail into the foreseeable future. This scenario — characterized by “no peace, no war” — will continue to be in the interest of the incumbent leaders who remain in power through power-sharing arrangements rather than through the ballot box. This scenario is unsustainable, however, and it will certainly aggravate the suffering of the people of South Sudan.

For South Sudan to transition toward viable statehood and ameliorate the suffering of its citizens, the following strategic interventions are critical:

Encompassing Leadership. The process of transition to statehood has been marred by the morbid working relationship enshrined in the shared leadership model between President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar, which is rooted in a history of grudges and power struggles. This shared presidency, as dictated by power-sharing arrangements negotiated over the years, has proven detrimental to the security of South Sudan.

This cycle can only be broken by allowing citizens to elect leaders of their choice through elections in 2023 as provided for in the peace agreement. If both opted to contest for the presidency in these elections, one of them might win, probably the incumbent president. However, given the turbulent history between these leaders and their ethnic constituencies, elections would be seen as a zero-sum game. This process, therefore, would likely be marred by division, violence, and deepened mistrust and antagonism.

Another option is to conduct elections without the two leaders. This option rests with their voluntarily acceptance not to run but to allow their parties to elect other candidates to contest for the presidency. This option is unlikely, but it is possible if the two leaders had an incentive to accept it. If this option were pursued, it would provide a glimpse of hope for producing the much-needed encompassing leadership.

The caveat of this option is that changing leaders is not a panacea for addressing the fundamental challenges facing South Sudan. This will require not only new but strategic and visionary leadership. The international community and friends of South Sudan, therefore, need to exert due pressure on both leaders, not only to refrain from running in the 2023 elections, but to work together in championing a national campaign for social cohesion, reconciliation, and healing of the nation.

People-Centered Constitution. The process of permanent constitution-making as provided for in the 2018 peace agreement avails a golden opportunity to learn from previous mistakes and to adopt a people-centered, inclusive, and participatory process that involves all stakeholders. If this process is managed well, it could correct the foundational flaws in the current Constitution. Namely, it would uphold the separation of powers, establish clear checks on the executive, adopt a decentralized federal system, and forge a new social contract, which is essential for sustaining peace, stability, and the viability of state of South Sudan. Kiir’s launch of the permanent constitution-making process opens the door to correct these flaws. To do so will require involving a greater representation of interests than those that have generated the current Constitution or subsequent peace agreements that merely solidified the status quo.

National Security Strategy. The current state of the security sector is a recipe for a cycle of violent conflict and fragility. Restructuring this sector needs a framework to build a new national security force from a clean slate. This framework would inform strategic decisions related to the size of forces, structure of the security sector, division of labor, decision-making and oversight mechanisms, civilian oversight, DDR, and the allocation of resources. It would also provide a national security strategy that is informed by a shared national vision and values, national security interests, and a thorough audit of the security sector and assessment of security threats and opportunities. The process of developing such a framework needs to be inclusive, participatory, and people-centered with focus on citizen rather than regime security. The 2018 peace agreement recognizes the need for such a framework by providing for the development of a white paper on defense and security to guide the rebuilding of the security sector. Unfortunately, this provision has thus far been disregarded.

Transitional Justice. South Sudan at 10 years of independence is in a grave state. The Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan, established by the United Nations Human Rights Council has observed that while the Peace Agreement has brought a lull in fighting at the national level, 75 percent of the country remains engulfed in brutal violence at the local level. Moreover, the Commission notes that “more than two years since the signing of the Revitalized Peace Agreement … South Sudan has made little concrete progress in establishing any of the transitional justice mechanisms” provided for in the Agreement. To change this downward trajectory while providing the space and requisite assurances to all sides, transformative remedies will be needed. The decision by the government, after 2 years delay, to initiate the process of establishing the joint African Union-South Sudan Hybrid Court is a step in the right direction to address the wounds of the past and legacy of gross human rights violations. Now, such political rhetoric needs to be put into action.

Additional Resources

- Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan, “Despite Renewed Commitment, Staggering Levels of Violence Continued in South Sudan for the Second Successive Year, UN Experts Note,” Office of the United Nations Human Rights Council, February 19, 2021.

- Luka Kuol, “When Ethnic Diversity Becomes a Curse in Africa: The Tale of Two Sudans,” Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, Vol. 21(1), 2020.

- Luka Kuol, “South Sudan: The Elusive Quest for a Resilient Social Contract,” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding,Vol. 14, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Envisioning a Stable South Sudan,” Africa Center Special Report, No. 4, May 2018.

- Kate Almquist Knopf, “Fragility and State-Society Relations in South Sudan,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies Research Paper, No. 4, September 2013.

This text was first published 29 June 2021 by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.