When personalistic dictators go to war, they are more likely to miscalculate and lose than leaders of other types of regimes. Such failures can have dramatic consequences for the stability of their regime at home, as well as for the rest of the world.

Photo: kremlin.ru

Russia’s grotesque invasion of Ukraine is one of the most horrific acts of aggression seen in Europe since the Second World War. The invasion emphasizes the inherent institutional weaknesses of having a personalistic dictator such as Vladimir Putin in charge of decision-making.

The Perils of Personalism

Putin, having spent the last two decades amassing power within Russia, is joining the ranks of other personalistic dictators such as Saddam Hussain, Idi Amin or Mao Zedong.

Jessica Weeks, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, identify these civilian dictators as ‘bosses’, leaders who tend to hold strict control of their countries’ internal and external security apparatus, and thus have very few institutional constraints that can hold them accountable for their actions.

They also tend to have personalities that favor the use of violence to solve policy problems – a learnt experience, as violence often is precisely what helped keep them in power.

Lastly, these dictators also tend to cut themselves off from high-quality information, and are surrounded by sycophants who have an interest in telling them what they want to hear.

Put simply, when you are alone at the top and surrounded by advisors that either not dare question your ideas or have an interest in telling you that you are right, that leaves you in a situation where you make bad policy-decisions. As such, using a data set on wars from 1921 to 2007, Weeks (2014) finds that personalistic dictators tend to initiate interstate wars more often than leaders of other elite-constrained autocratic regimes or democracies. Moreover, these dictators also tended to lose the wars they initiate (losing 56-73% of initiated wars) more frequently than their democratic and elite-constrained counterparts (losing 26-28% of initiated wars).

Isolated at the top of the Russian system, and in control of one of the world’s largest militaries and nuclear arsenals, Putin fits all the characteristics of dictator ready to make a bad decision. The decision to invade Ukraine appears to be just that.

Poor Planning and Unanticipated Costs

Dictators such as Putin may favor acquiring prestigious and shiny weapons (such as Russia’s new hypersonic missile system) that can be displayed as propaganda rather than investing in costly and unnoticed attributes of the military, such as logistics.

Various commentators have pointed out that Putin’s invasion has suffered from an acute lack of logistical support, resulting in 60 kilometer long caravans of Russian vehicles waiting for fuel and repairs. These have, according to U.K. intelligence, come under heavy attack by Ukrainian forces. Logistics experts have previously noted that Russia does not have the logistic capabilities to sustain a long-distance ‘blitzkrieg’ such as its current invasion of Ukraine. It is possible that Putin was aware of this limitation, but that he still believed in a swift and winnable war against Ukraine.

Images from the remote sensing company MAXAR captured the extent of the Russian invasion’s logistics failure.

Indeed, Ukrainian resistance has proven to be much stronger than what Putin anticipated. Ukrainian soldiers and civilians appear motivated and are armed for asymmetric resistance.

Footage from the front lines have shown unarmed Ukrainian civilians preventing Russian tanks from traversing towns and protesting Russian occupation while being threatened by live ammunition, underscoring the courageousness and morale of Ukrainian resistance. On the other hand, many Russian soldiers were wholly unprepared for the realities of attacking Ukraine.

Two weeks after the onset of the invasion, Putin’s only significant military achievement is control of the southern Ukrainian city of Kherson. This comes after Russia fired over 600 ballistic missiles at Ukraine as well as employed over 95% of its amassed combat power, according to a senior U.S. defense official. While it is impossible to know the real Russian casualties so far, accounts from both Ukraine and Russia already point to thousands of deaths, overall suggesting heavy Russian losses. While long-term brute force may result in some form of pyrrhic victory for Putin, the costs for Russia would likely be extremely high.

Burgeoning Domestic Instability

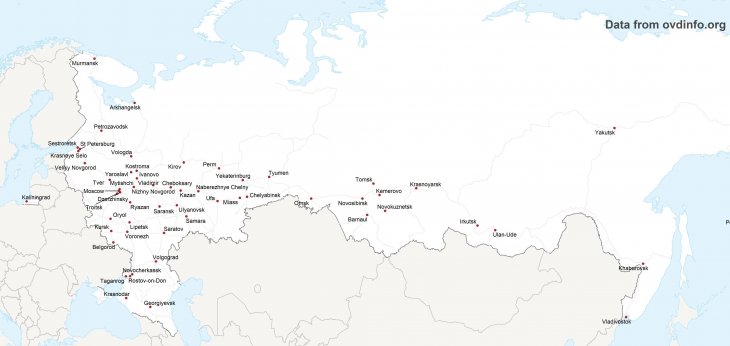

At home Putin faces massive anti-war protests and economic instability. Data from the independent tracker OVD-info have recorded protest-events in over 150 Russian cities, and at the time of writing some 13’790 Russian citizens have been arrested for taking part in protests against the war (9th of March).

Recorded protests in major Russian cities by OVD-info.

The ruble has fallen drastically vis-à-vis the dollar and euro following the implementation of massive sanctions from the European Union and the United States. Videos from last week have shown ordinary Russian citizens queuing-up to take out cash from ATMs in the anticipation of their personal banks collapsing. Western companies are pulling out from Russia, and oil and gas prices are souring due to a U.S. ban on oil and gas imports from Russia, something that would further hamper the Russian economy.

Some commentators have already suggested that that the piling military and economic costs of the invasion may be the undoing of Putin’s regime in the mid- to long-term. However, as Jessica Weeks and Jeff Colgan point out in Monkey Cage, his control of the internal security apparatus in combination with Russia’s access to vast oil reserves makes him comparatively strong in comparison to other dictators in his position, something that may make him more reckless when confronted with push-back. The increased shelling of civilians in Ukraine seen the last week may be an early indication that Putin is employing similar tactics as during his interventions in Syria and Chechnya.

Why Everybody Loses

While the brunt of Putin’s aggression is suffered by Ukraine, the war already casts a dark cloud over the world economy. Destabilized by a new strain of COVID-19, the world economy was forecasted to experience a major correction this year, to which the invasion of Ukraine certainly contributes. Putin also took Europe dangerously close to an international environmental crisis this weekend following Russian shelling of Europe’s largest nuclear power plant in Enerhodar, Ukraine. His actions have global ramifications, and as such personalistic dictatorship may be akin to what Groot, Bozzoli, Alamir et al. (2022) call ‘global public bads’, similar to other global problems such as pandemics and climate change.

Putin’s war illustrates how the actions of a single autocratic leader can have a dramatic impact on our lives and further underscores the value of global democratization.

The author

- Jens Koning is a Master’s student at PRIO