In spite of widespread support for the sanctions against Russia after the invasion of Ukraine, international economic sanctions remain a controversial instrument in world politics.

In this blog post, we discuss how the ethical criteria of just cause, proportionality, last resort and reasonable chance of success can help us think about the justice of sanctions.

Photo: Jernej Furman / Flickr / CC BY-2.0

Lawful – but ethically justified?

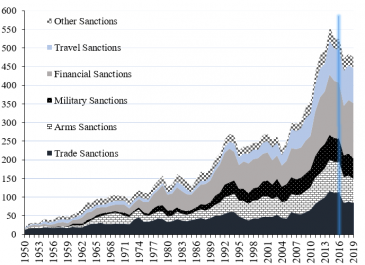

The use of international sanctions has increased steadily since 1950, and the number of UN Security Council mandated sanctions soared when the Cold War ended (see Figure below). In spite of this, little public attention has been devoted to how the justice of sanctions regimes should be assessed.

Source: Global Sanctions Data Base

In the Global Sanctions Data Base, international sanctions are defined as ‘restrictive policy measures adopted by individual countries, groups of countries, the United Nations and other international organizations, to address various types of violations of international norms and conventions’ (p. 5). As an alternative to warfare, sanctions through restrictions on trade, finance, arms and travel are among the few international coercive instruments at the disposal of states. In distinction from military aggression, sanctions are generally lawful, also without a UN Security Council mandate. When adopted multilaterally, they even serve to reinforce international law.

Yet, economic sanctions are often criticised for being disproportionately harmful, for lacking in effect, or even being counterproductive. Also when lawful, sanctions are not necessarily the right thing to do from a moral perspective. And sometimes things that are unlawful may be taken to be morally justified. Consider laws in an authoritarian regime like North Korea. Some would say that international law is hampered by an immoral reliance on the self-interest of major powers, as reflected in the veto powers of the UN Security Council.

No universal answer exists as to whether economic sanctions are morally right or wrong. It depends on the circumstances. Still, when considering particular cases we inevitably operate with general concepts and assumptions that require critical examination.

Sanctions as a blunt weapon

Ukraine

Massive economic sanctions have been used as a weapon short of war in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In spite of a lacking UN Security Council mandate due to Russia’s veto power, supporting these sanctions is commonly perceived as a moral obligation.

Given Russia’s crime of aggression, states have a general responsibility to respond collectively to such violations for the maintenance of international peace and security. As exemplified by the military response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, this would even have warranted international military intervention to support Ukraine in defending its borders. In the absence of a UN Security Council mandate for such action, however, combined with the threat of Russian nuclear weapons, international economic sanctions seem like an uncontroversial alternative. Yet, provided the limited effects of the sanctions so far, combined with the costs for Russian citizens and for others affected by hampered trade and Russian counter-measures, it is questionable whether the sanctions are ethically justifiable overall.

Afghanistan

Meanwhile, the multilateral sanctions on Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover in 2021 have been heavily criticized due to their toll on the Afghan people. The sanctions have crippled the economy leading to widespread poverty, without succeeding in changing the ways of the regime. The United Against Inhumanity campaign for the release of Afghanistan’s frozen funds recently stated: ‘It is morally, politically, and economically wrong to make the people of Afghanistan pay – often with their lives – for a crisis not of their making.’

Venezuela

In the case of Venezuela, the Government sees the US sanctions against it as unlawful and even referred them to the International Criminal Court for amounting to crimes against humanity! While this may be seen as a political tactic, it raises the question of whether sanctions can reach a threshold where their effects are so grave that they violate international law.

Syria

Regarding Syria, the Special Rapporteur of the UN Human Rights Council, Alena Douhan, urged sanctioning states to lift unilateral sanctions against the country, warning that they were ‘perpetuating and exacerbating the destruction and trauma suffered by the Syrian people since 2011.’ Evidently, lifting these sanctions would go against Western policies of holding the Assad regime accountable for mass atrocities during the civil war, and would send the signal that if regimes succeed in maintaining power through immense brutality they will benefit in the longer term. On the other hand, the sanctioning states currently signal that they will abandon the immediate needs of the people in Syria in pursuit of their principled longer-term policies.

When are sanctions justified?

In the language of ‘Just War Theory’, Russia’s crime of aggression is a just cause for war. Still, a just cause does not itself justify the resort to war – even if lawful. According to the just war tradition, six other criteria are usually considered important to justify a resort to war: proportionality, right intention, legitimate authority, last resort and reasonable chance of success.

Leaving aside the question of legality, the same criteria might be used to consider the ethical justification of resorting to economic sanctions. This is not to say that the exact same requirements apply to sanctions as to war within each of the criteria. For instance, only international aggression (and, more controversially, mass atrocities) is usually taken to be a just cause for war – while this seems too strict a limitation for economic sanctions.

In the following, we suggest how the just war criteria can be applied to sanctions, with examples from the current international sanctions on Russia and beyond. We consider what we take to be the most relevant aspect of Just War Theory in relation to sanctions: Just cause, proportionality, last resort and reasonable hope of success. While right intention and legitimate authority also merit analysis, we doubt that these criteria are decisive for whether sanctions are ethically permissible all things considered.

Just cause

When the crime of aggression is a just cause for war, the same presumably also can be said for economic sanctions if the harm caused by sanctions is more limited than from a military response. However, this parallel between war and sanctions assumes that economic sanctions are an adequate way of responding to a crime of aggression. There is a widespread assumption that this is the case – but as we will see in the following, the connection is not as straightforward as with military action against an army that has invaded another country.

On the other hand, sanctions are commonly used in response to a variety of causes beyond aggression or mass atrocities – from reacting to a regime’s domestic policies such as the apartheid regime in South Africa, to managing a security threat like North Korea nuclear weapons programmes. If sanctions are justified in these cases, then sanctions in response to the military aggression of Russia seems unproblematic provided that the other criteria, like proportionality and likelihood of success, are also met.

Proportionality

Proportionality is one of the most important criteria set up by the just war tradition to assess whether resorting to war is justified. The proportionality criteria requires that the harm caused by resorting to war does not outweigh the benefit of going to war is likely to achieve. Unlike proportionality in punishment, proportionality in war is usually interpreted exclusively forward-looking. This means that for a war to be proportionate, it must be proportionate to the good it may achieve – not to the wrongful harm the attacked party may already have suffered.

Although proportionality is about weighing good and bad consequences, this is not done in a standard ‘consequentialist’ manner. Firstly – harm inflicted on civilians is typically attributed more moral weight than harm inflicted on soldiers. Secondly, all good and bad consequences are not counted in a proportionality assessment. For example, the fact that great literature or art is often produced during war, or that war spurs technological development, is not typically taken into consideration as a relevant good achieved by war to be weighed against its evils.

The sanctions against Russia over the war in Ukraine demonstrate the relevance of this question of which good and bad consequences should be included when we consider whether sanctions are proportionate. On the negative side, it leads to reduced welfare for parts of the Russian population and increases energy prices in Europe. This should count as a negative effect of the sanctions, to be weighed against the benefits that sanctions can be expected to achieve. The expected adverse effect sanctions have on Russia’s ability to continue its military offensive counts on the positive side. So far so good. But consider other possible positive effects of the sanctions: The restriction of gas to Europe may ideally lead to increased investment in energy efficient technology and renewable energy, which benefits the environment. Should we think that such potential positive effects of the sanctions can be weighed against the harms the sanctions cause? Or are these analogous to great art and literature the war example, i.e. goods that we should consider irrelevant to the proportionality assessment?

When it comes to proportionality assessment, it may seem that we should understand this criteria in the same way as we when we assess whether wars are justified. As the Canadian philosopher Tom Hurka says in the context of war: ‘There is […] a thumb pressed down on one side of the proportionality scale, with more counting on the negative than on the positive side’ (p. 46). Precisely how we restrict the goods that we can include in the proportionality assessment when it comes to sanctions, is therefore an important question which may greatly influence our view of which sanctions are justified.

Last resort

According to Just War Theory, warfare is justified only when all other options have been exhausted or are unavailable. Going to war must be a last resort, on the assumption that war is the worst option among all other that have a reasonable chance of success in dealing with the aggression in question.

If wars are justified only as a last resort, it follows that the last resort condition cannot apply as well to sanctions. But, if economic sanctions are ranked second after wars among the options to be avoided, then the last resort condition as applied to sanctions should be formulated as follows: Apart from war, economic sanctions are justified only as a last resort. This formulation does not exclude that resorting both to military action and economic sanctions (as in the case of responding to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine) can be justified. This would be the case when both war and sanctions are needed to achieve the aims in question.

Reasonable chance of success

As with wars, economic sanctions, especially broad ones, can cause serious collateral harm to civilians. Hence, they are justifiable only when they have a reasonable chance of achieving their aims. Most critics of economic sanctions focus on their ineffectiveness in achieving their end goal. The common perception is that the sanction regimes imposed on Iraq, Iran, North Korea and Venezuela have failed to produce the desired results, but have inflicted great human suffering.

Assessing the effectiveness of sanctions is not straightforward. Consider Iraq and Iran. The aim of sanctions imposed on Iraq after it attacked Kuwait was to prevent Saddam Hussein’s regime from developing weapons of mass destruction or attack other countries. Later developments showed that both aims where achieved. Iraq did not attack other countries and did not continue to produce weapons of mass destruction. The latter is evident by the fact that the case made by the USA for invading Iraq in 2003, on the ground that Iraq was engaged in the production of weapons of mass destruction, turned out to be false. Hence, it cannot be said that the sanctions on Iraq failed to achieve their aim.

The same applies to a certain extent to sanctions imposed on Iran. The main aim of the Iranian sanctions was to prevent it from developing its nuclear capabilities. The deal which the US Obama Administration signed with Iran was based mainly on lifting sanctions in return for guarantees that Iran would curb its nuclear programme and place it under a UN inspection regime. Supporters of the Obama nuclear deal with Iran must also concede that the sanctions were instrumental in convincing Iran to agree to keep its nuclear capabilities below a dangerous threshold.

It might be true that, for both Iraq and Iran, sanctions did not lead to regime change. However, the latter was only a desirable collateral outcome, but not part of the declared aims of the sanctions.

If the ex-post assessment of the success of sanctions, as the cases of Iraq and Iran show, is not a straightforward matter, then one should expect an ex-ante assessment of the success of sanctions to be a much more difficult affair. The sanctions against Russia fall in this category.

Things become even more complicated if deterrence is considered as part of the aims of sanctions. Sanctions against Russia work as a deterrent if they reduce the chance that it might invade other countries in the future, or if they reduce the possibility that China will invade Taiwan. While it is not implausible to think that the sanctions against Russia would play such a deterrent role, it is difficult to verify.

- This blog is published in continuation of the seminar: Just Economic Sanctions? You can listen to a recording from the event on the PRIO event page. The text draws on insights from discussions in the seminar and an ensuing roundtable discussion, and we thank the participants for their valuable contributions.

Further reading

Notable contributions to the ethics of international sanctions include the work of Jay Gordon and George A. Lopez. See e.g. Gordon (2011) Smart Sanctions Revisited, Ethics & International Affairs, 25(3): 315-335; and Lopez (2012) In Defense of Smart Sanctions: A Response to Joy Gordon. Ethics & International Affairs, 26(1): 135-146.

Further discussion

For further discussion on the relevance of just war theory to sanctions, which also addresses the criteria of right intention and legitimate authority, see e.g. Bryan R. Early and Marcus Schulzke (2019) Still Unjust, Just in Different Ways: How Targeted Sanctions Fall Short of Just War Theory’s Principles, International Studies Review 21: 57–80; Elisabeth Ellis (2021) The Ethics of Economic Sanctions: Why Just War Theory is Not the Answer, Res Publica 27: 409–426; and Albert C. Pierce (1996) Just War Principles and Economic Sanctions, Ethics and International Affairs 10: 99–113.

The authors

- Lars Christie is an Associate Professor at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

- Bashshar Haydar is a Professor of Philosophy at the American University of Beirut

- Kristoffer Lidén is a Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)