Against the backdrop of the grisly Russia-Ukraine war, the security situation in East Asia may appear conducive to the continuation of the long peace that the region has enjoyed for decades.

However, the devastating European war has cast a long shadow eastwards.

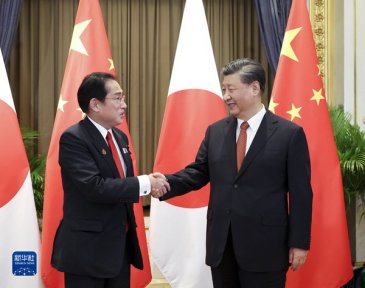

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida shakes hands with Xi Jinping at their meeting in Bangkok in November 2022. Photo: FMPRC

While Russia’s military presence in Asia is deeply curtailed as most of its conventional capabilities are redeployed to the Donbas front in Ukraine, the behavior of maverick North Korea has become more reckless and China’s policy has become less predictable and more assertive.

As a result, Japan has adopted a more proactive approach to its international security environment predicated on enhancing its military capabilities and deepening security cooperation with key allies and partners, starting with, but not limited to, the U.S.

Charting a New Security Course

Japan’s response to these aggravated security challenges is codified in the new National Security Strategy (NSS) approved in mid-December 2022 then elaborated in the National Defense Strategy and the Defense Buildup Program (Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan [MOFA], December 27, 2022; Japan Ministry of Defense, December 28, 2022).

These documents contain few surprises, as the content was subject to many in-depth debates; yet, they constitute a major departure from the familiar patterns of cooperative relations with Japan’s very different and often difficult neighbors (ECFR, January 31).

The commitment to patient and persistent work aimed at resolving disagreements is deeply ingrained in Japanese strategic culture, so the recognition of the plain fact of irreconcilable conflict with the nuclearizing North Korea and war-bent Russia took no small amount of political courage. [1]

Even more difficult is internalizing the prospect of irreducibly hostile relations with China, which has embraced strategic competition with the U.S. and constitutes a direct and growing threat to Japan’s security interests (Nikkei Asia, January 17).

Indeed, such a course ensures continued criticism from Beijing that Tokyo enables and supports what the PRC foreign ministry describes as U.S. machinations to assemble “small blocs through its alliance system that “create division in the region, stoke confrontation and undermine peace” (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs [FMPRC], February 20).

This shift in Japan’s fundamental views on regional security is on par with Germany’s abandonment of the political tradition of Ostpolitik, based on the assumption that cultivation of economic ties with the Soviet Union and then Russia would ensure a peaceful evolution of the European security system. The new German policy aimed at deterring and defeating aggressive Russia, which introduced into the political lexicon the term Zeitenwende, remains unstable and is even compared to the famous “Schrödinger’s cat”, which is presumed to be simultaneously alive and dead. [2]

Japan’s new course is by no means free of controversies, but it is charted unequivocally and firmly set.

Collective Security is Hard Work

As Japan increases its defense budget and invests in new long-range capabilities, its leadership clearly understands that managing an increasingly challenging regional security environment also requires a collective effort.

This emphasis on expanding ties with allies and partners aligns Tokyo with U.S. President Biden’s big idea of building an alliance of democracies and the more specific goal of deterring China’s expansionism through the combined efforts of all regional security stakeholders (The White House, October 12, 2022).

For Washington, the combined application of ideological and geopolitical frameworks to deal with China appears on the mark, but in order for the U.S. and its allies to successfully implement this approach, they must overcome multiple points of tension and even disagreements over how best to manage the challenge at hand (South China Morning Post [SCMP], January 7).

One of the main concerns shared by Japan, as well as most of the other East Asian participants in the coalition of democracies, is the reliability of the U.S. commitment to the region. Few doubt the durability of the U.S.-China rivalry, but suspicions linger about a possible shift in attitude under the next U.S. administration toward regional allies.

Moreover, these East Asian partners must also grapple with demands from Washington to enforce restrictions on economic ties with China, which affect trade and investment flows in Asia-Pacific (Japan Times, November 25, 2022). A larger issue is the prospect of an extended Russia-Ukraine war of attrition, which could force a shift in U.S. attention and military resources away from East Asia.

A key part of the solution to this problem is adding regional security links to the bilateral ties with the U.S., with the recently strengthened cooperation between Japan and the Philippines providing an excellent case in point (Kyodo News, February 9). Moreover, Beijing has noted this increased bilateral cooperation with pronounced displeasure, which underscores its utility (Global Times, February 13). Taiwan is also keen to upgrade its security relationships with Japan and South Korea, despite the constraints imposed by the firm adherence of both Tokyo and Seoul to “One China” policies (Taipei Times, February 15). This ambivalence illustrates the difficulties in expanding regional networks, which are often deformed by old grievances, for instance, between Japan and South Korea.

Another challenge that East and Southeast Asian states must overcome in order to deepen regional security networks is integrating their differing security priorities. South Korea is heavily focused on the threat from North Korea, whereas the Philippines and Singapore are concentrated on tensions in the South China Sea. Japan finds itself in a multi-threat environment, with the Northern Territories in dispute with Russia, tensions with China in the East China Sea, the threat from North Korean nuclear-capable missiles and direct exposure to a potential conflict in the Taiwan Straits.

Russia: Weak Link and Wild Card

China is also actively building out its own security networks by cultivating ties with Myanmar and recently making a major upgrade to its relationship with Iran (China Daily, February 17). The main pillar of these connections is the strategic partnership with Russia, but this quasi-alliance may turn out to be a source of trouble rather than strength.

Russia has for many years attempted to execute a “pivot to Asia”, but its economic profile has amounted merely to exports of oil and gas, mostly to China, so it has had to rely on demonstrations of military might to claim a prominent role in regional security. During the last year, a major part of its conventional capabilities, including the marine brigades of the Pacific Fleet, were redeployed to the Ukraine theater and have suffered heavy losses as a result (Moscow Times, February 14).

Russia is keen to prove that its military profile is undiminished in the Pacific and has recently undertaken a series of joint naval exercises with China. In September, a combined naval squadron sailed through the Osumi Strait, which separates the southwestern tip of Kyushu from the Ryukyu Islands (Nippon.com, September 30). In December, another joint China-Russia naval exercise was held in the East China Sea (China Military Online, December 21, 2022). Russian long-range aviation, despite performing frequent combat missions against Ukraine, is also conducting Pacific patrols, sometimes together with Chinese H-6K strategic bombers (Nikkei Asia, November 30).

As worrisome as these demonstrations of military force are, they cannot conceal the severe degradation of the Russian defense-industrial complex and the lack of material support from China to its partner-in-need. Moscow was irked by the warning by State Secretary Antony Blinken regarding China’s considerations over providing “lethal support” to Russia, delivered at the 2023 Munich Security Conference (TASS, February 19).

Moscow has tried to sustain an offensive push in Donbas, but the balance of forces is shifting against it as the Ukrainian army receives increasing amounts of modern weaponry from the West. The only hope for Russia to alter these dynamics is an escalation of conflicts in East Asia, which would force the U.S. to shift attention and military resources to the Pacific.

Russian analysts express concern about the changes in Japan’s defense policy and try to argue that financing the planned military build-up is a burden too heavy for the state budget. [3] Such wishful reflections cannot hide the desire to see a surge in tension between China and the U.S.-Japan alliance. For example, the recent crisis involving the Chinese intelligence balloon and other unidentified objects, which has roiled U.S.-China relations, has been monitored and amplified with acute interest in Moscow (Kommersant, February 13).

Russia may find itself in an increasingly desperate situation as Ukraine prepares a spring counter-offensive. As a result, for the Kremlin, an escalation in the Pacific could become a practical necessity.

Taiwan is generally beyond Russia’s reach and triggering a clash around the Kuril islands could be self-defeating, but the small group of uninhabited islands in the East China Sea, known as Senkaku in Japan and Diaoyu in China, could present a useful target. The Japanese government took ownership over these islands in 2012 and took pains to explain to Beijing its reasons for that nationalization, but China still vehemently opposed the move and continues to contest Japanese administration of the islands (Kyodo News, December 16, 2022).

The meeting at the 2023 Munich Security Conference between Japanese Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi and Wang Yi, Politburo member and senior-most PRC foreign policy official, could bring some reduction in tensions around the Senkaku/Diaoyu (Japan MOFA, February 18). Nevertheless, Moscow could look for a chance to stage a “false flag” operation or another of the sort of “hybrid” provocations that it excels at.

Conclusion

Time is a crucial resource for executing the planned changes in Japan’s defense policy, but the dynamics of the Russia-Ukraine War have seemingly shortened the timeline for Tokyo to achieve its goals. The Japanese government needs to encourage every step taken by Xi Jinping in the direction of returning China to the trajectory of strong growth by luring back wary foreign investors and de-escalating conflicts with the U.S., Taiwan and Japan.

Tokyo can count on the Biden administration, which seeks to balance firmly responding to persistent Chinese probes of its resolve with keeping competition with its main geo-economic rival on an even keel, doubling this encouragement.

What Tokyo cannot count on is Xi Jinping’s sustained preference for prosperity through normalizing regional interactions. The domestic economic situation in China is more uncertain than its leaders are prepared to admit, and another surge of public protests could prompt a high-level decision to resort to aggressive nationalism as a means of restoring control. Furthermore, the recent emphasis by Beijing on achieving “self-reliance in science and technology,” which was the theme of the Politburo’s most recent collective study session, underscores that the PRC is girding itself for long-term geopolitical competition with the West (State Council Information Office, February 22).

The obvious lesson of the Russia-Ukraine war for Beijing is to reassess the strength of the Western alliance and to avoid brazen and costly experiments with projecting military power.

However, the PRC can also draw less obvious lessons on the consolidation of autocratic control in the course of Russia’s confrontation with the U.S.-led coalition. Europe must prepare for the grim prospect of a long war, but the best way to ensure a stable peace — and to reduce conflict potential in East Asia as well — may well go through helping Ukraine achieve a swift and decisive victory.

President Volodymyr Zelensky presented this option at the 2023 Munich Security Conference, and it is by no means a stretch of his strategic imagination. Russia’s defeat can be brought much closer than the delusional Kremlin expects, and Japan can contribute to joint efforts aimed at this rehabilitation of a rules-based world order.

Notes

[1] This observation is based in part on the author’s recent research trip to Tokyo, where he (together with PRIO colleague Dr Ilaria Carrozza) held discussions with security experts at leading Japanese think tanks.

[2] See, Constanze Stelzenmüller, “Germany’s policy shift is real but still falls short,” Financial Times, February 13, 2023.

[3] See, Andrey Kortunov, “Old Cold War type relations do not serve Japan”, Russian International Affairs Council, January 18, 2023.

- Pavel K. Baev is a Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO).

- This text is also published by the China Brief 3 March 2023