Initial Western support for Ukraine in the face of murderous Russian aggression was strong and unified. With Putin’s ambitions to capture Kyiv in shambles, Ukraine’s survival has been assured, but the war drags on.

Picture created with Dall-E version 2, using the prompt “White crosses on a military cemetery stretching all the way to the horizon on a gray, misty day, oil painting”.

The Ukrainian government has set its sights on absolute victory, including retaking the territories Russia occupies since 2014, reparation payments, extradition of war criminals, NATO and EU membership, and lasting societal change within Russia to tame its expansionist ambitions.

How these goals will be reached without invading Russia for fears of nuclear escalation is not clear, and several well-informed voices stress that absolute victory in Ukraine is very unlikely.

Naturally, painting pictures of bottomless resolve is part of the staring contest in attrition war. However, this stance comes at significant costs. The absence of a military end-game generates a dangerous void both within and between the conflict parties. The trench warfare on the Eastern Front has become a Rorschach Test for diverging national memories within Europe and a canvas of propaganda for Putin. The associated tensions will increase, unless Western leaders begin to build coalitions around clear and realistic war aims.

The ghosts of World War II

The one-year mark of Russia’s invasion has seen an impressive display of Western unity. The G7 has announced open-ended support for Ukraine, and NATO’s commitment is unwaivering. Military assistance is considered a bi-partisan issue in most European countries. Below the surface, however, European electorates have split into diverging camps.

The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) has surveyed two broad currents in global audiences.

Camp Peace

Camp “peace” wants to see a quick cessation of hostilities, to alleviate the suffering in Ukraine and limit the global knock-on effects of the war. The permanent loss of Ukrainian territory is acceptable to this group of respondents.

Camp Justice

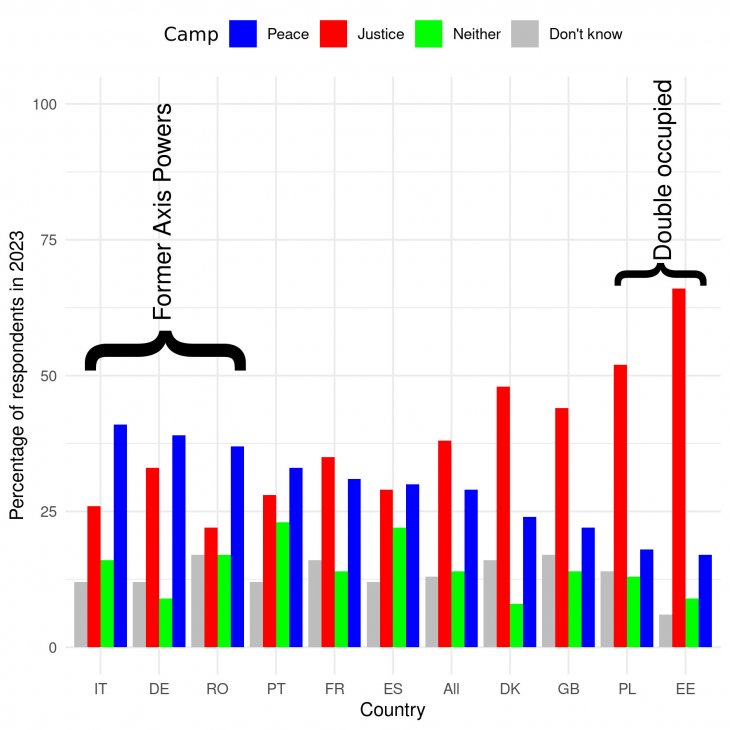

Camp “justice” opposes this view, and instead wants to see Ukraine regain control over all of its territories. A longer war entailing higher costs and casualty counts is acceptable to them. This of course, is also the official Western position, the de-facto journalistic consensus, and the only tolerated stance on social media. Within Europe, “justice” is also the majority view, but to a much lesser extent than official posturing would suggest: 38% of respondents in nine surveyed EU countries are on team “justice”, as opposed 29% on team “peace”, with the rest being undecided.

The ECFR suggests several reasons for why “justice” has become a majority view, but the big picture in their results is one of diverging national memories of their last war. In both 2022 and 2023, the European “peace” camp is dominated by the former Axis Powers, Germany, Italy, and Romania. Poland and Estonia, the double victims of Nazi and Soviet occupation, lead the “justice” camp. Other European countries reside in the middle, as shown below.

This plot was created by Sebastian Schutte based on the data reported by ECFR. It shows survey responses in 2023 ordered by size of the “peace” camp.

These results reflect three principle European experiences from the last Great Power War: the double trauma of having suffered under the Nazis and the Communists, the bottom-line experience of having successfully resisted the Nazis, and the deep-seated aversion to war that results from having been the Nazis.

“Slava Ukraini!”

Ukraine, whose determination will be remembered for generations, did not rise to the occasion spontaneously. When confronted with Russian aggression today, Ukrainian memories of occupation and genocide translate into iron resolve to win this war. Most empathy for this perspective can be found among other double-victims of World War II, such as Poland and Estonia.

Their fate has mirrored that of Ukraine for large parts of the last century. Deprived of national self-determination following the Hitler-Stalin pact, Poland suffered the full brunt of World War II. The eastbound sweep and westbound collapse of the German front lines brought total destruction to every major city in Eastern Europe. Behind German lines, Poland was turned into ground zero for the Holocaust, suffering through the industrial genocide of Auschwitz, Treblinka, and the Warsaw Ghetto.

In Poland, Estonia, and Ukraine, the partisans who provided vital assistance to the advancing Red Army split into communist and nationalist groups after the war, with those fighting for national independence mounting a strong, costly, and ultimately ill-fated resistance against the Soviet Union.

Against this backdrop, the historical memory evoked by Russian aggression today is intense. Putin is compared to Hitler and Stalin (and found to be more dangerous), by Polish Prime Minister Morawiecki. One of his top ambassadors contemplates entering the war in case of imminent Ukrainian defeat, to defend Poland’s way of life. The current struggle against Russia is seen as existential among those who lost their freedom for half a century to two aggressors in World War II.

“We shall never surrender!”

With lines like “I need ammunition, not a ride”, the Zelensky-Churchill comparison is certainly not lost on the British or the Danes, comprising the second strongest “justice” camps. Ukraine’s last year bears strong resemblance to the British situation in 1940, when the “Third Reich” had occupied the continent and set its sights on the remaining resisting island. As Churchill was promising infinite resistance even after a possible occupation, Americans were stuck in heated debates over lend-and-lease weapons deliveries, and whether they violated the Monroe doctrine.

In this crucial situation, the British stood their ground, and were rewarded with victory five hard years later. In those five years, they carried the hopes of German-occupied countries across Europe. Resistance movements in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway, all interacted with the British, contributing reconnaissance, sabotage, and even extraction of downed air crews. Those contributions were critically important to the eventual liberation of the continent.

To the nations that stood firmly in the face of overwhelming German aggression, the lesson is clear: damn the torpedoes and win the war! Supporting Ukraine in its fight against contemporary Russian aggression is a strongly-held majority position here, albeit to a lesser degree than in Eastern Europe.

“Nie wieder Krieg!”

The European “peace” camp is dominated by the former Axis Powers, Germany, Italy, and Romania. Especially Germany stands out globally as the one nation grateful for having lost a major war. The victory celebrated on May 8 by the former allies is perceived as the day of liberation within Germany. Contemporary pictures of trench- and attrition war in Ukraine bring back memories of wrong-headed and futile German aggression, paving the way for unimaginable atrocities.

Such memories can be especially connected to appearances. Sending German “Leopard” tanks to kill Russians where German “Tigers” and “Panthers” from the wrong side of history did the same was a hard sell domestically. International pressure has broken German hesitancy, but not necessarily won hearts and minds in the process.

The German outlook on territory is also unusual. Prussia fought three wars of German unification after 1850 alone, each one changing borders. A German woman born in Leipzig in 1910 could have easily been a citizen of five different countries, without ever leaving the city. Her first Germany minus Posen, East Prussia, or Alsace-Lorraine would have seemed as unimaginable as the reunification of her last one.

Unlike nations defined by static natural boundaries, Germany is a fluid historical construct. This has given rise to an unusual easy-come-easy-go outlook on national territories. Putin’s formal annexations are despicable breaches of international law, but if German memory is any guide, they will go the way of Swedish Pomerania. Consequently, to many Germans, lines on the map and lofty promises are never worth the reality of carnage in modern attrition war.

All these diverging sentiments across Europe have one thing in common: they offer no clear-eyed solutions to the current war in Ukraine. Instead, they ignore the fundamentals of the military situation, muddy the Western policy debate, and supercharge the propaganda conflict with Russia.

Will the real Nazi please stand up?

For Putin, the conflicting signals from NATO are a godsend. After several attempts to find their pitch have come and gone, Russian propagandists have now settled on stopping NATO from destroying Russia.

In its long history, Russia has suffered from numerous invasions at trauma-inducing costs, rewarded by eventual success. World War II stands out with its unimaginable death toll, inflicted by an overtly genocidal enemy. Pictures of modern “NATOzism” can be invoked more easily, as long as the Western alliance subscribes to visions of changing Russia by force, which simply helps Putin rally the nation around the flag.

Russian exploitation of unclear Western war aims also served as packaging for one recent step toward nuclear escalation: Putin justified his exit from the “New Start” nuclear disarmament deal by stating that NATO was after nothing less than the disintegration of the Russian Federation. Biden promptly rejected the claim as completely implausible, while simultaneously stressing Ukraine’s right to determine the course of the conflict and that a Chinese peace initiative welcomed by Russia must be flawed exactly because it was welcomed by Russia. This is not how one drives a wedge between the Russian populous and the Kremlin, which is exactly what the imprisoned Russian opposition is asking us to do.

Even on the right side of history and far away from the battlefield, portraying the war as a fight against “Putler” and his “Orcs” is filling hearts with darkness. “The Sun” newspaper has found a new calling in life: they post video after video of sniped Russian soldiers and exploding Russian tanks on YouTube, without age-restriction. Google’s concerns over emotional harms inflicted by non-inclusive language do not generalize to concerns about the emotional harms done to children, who use their video platform to watch someone’s fiery death for entertainment. “Nazifying” every side of the conflict clearly contributes to such levels of dehumanization. Against the backdrop of both sides already violating Geneva Conventions, this is not the tone to strike. Alleged Nazis claiming to defend themselves against Nazis is a clear sign of conflict intractability, which nobody in their right mind should want to contribute to.

Overcoming historical biases to end this little world war

Each historical bias currently on display is unhelpful in its own right. The Eastern European prediction that Russian aggression will extend West into NATO countries overshoots the mark. Around 200,000 casualties and 2,000 tank losses ago, Russia was unable to take Kyiv. The only mode of fighting it has limited success with is a century old, and involves convicts and conscripts used as cannon fodder. The high-tech war in the opening days of the invasion has been comprehensively lost by Russia, and incursions into NATO territory would be beaten back swiftly.

It is therefore incorrect that the fate of global democracy hangs in the balance right now, despite Ukraine and the US framing it this way. The worst-case outcome for the war is not the beginning of a new Stalinist dark age engulfing Eastern Europe, but large-scale destruction and partial occupation of Ukraine.

Western World War II allies tend to depict victory in Ukraine in ways that are equally rooted in memory. However, the scenario from 1945, involving occupation of Germany and prosecution of war criminals seems unrealistic today when Russian nuclear doctrine is taken into account. Successful conventional invasion of Russian territory would likely lead to a nuclear response.

Ukrainian demands adopted by the West for the transformation of Russian society, reparations, and extraditions must therefore find historical predecessors elsewhere, such as in the punitive peace agreements after World War I. Their signing by the defeated sides was only possible beyond a pain threshold of millions of casualties. Russia was militarily defenseless and embroiled in civil war when Lenin signed off on Brest-Litovsk in 1917. One year later, the German Empire threw in the towel after four years of mostly two-front war, 7.1 million military casualties, and the starvation of more than half a million civilians as a result of the allied naval blockade. Whether it is possible or desirable to inflict comparable losses on Russia today is questionable.

Best-case outcome

More realistically, the best-case outcome for the war is therefore an effective cease-fire agreement, a withdrawal of Russian troops from newly occupied Ukrainian territory, a UN-implemented interim solution for Donbas and Crimea, and reparations paid from seized Russian assets. While this scenario falls short of Ukrainian demands – which are morally and legally justified – it can serve as a much stronger basis for a supporting political coalition in the West and would empower the Russian anti-war movement to question the pointless fighting abroad.

This goal should not be conflated with naive pacifism. The Axis Powers deserve a pat on the back for their come-to-Jesus moment, ending centuries of expansionism and militarism. But their “peace” camps cannot ignore the inevitable consequences of their demands to simply stop arms deliveries. This move would immediately put millions of Ukrainians in the path of an invasion that leaves nothing but murder, rape, and destruction in its wake.

However, the “peace” camp can correctly point to very positive results achieved by diplomacy: a recently extended grain export deal, prisoner swaps, exchanges of human remains for burial at home, and both sides expressing interest in meetings with Chinese delegations. A combined military-diplomatic strategy will be required to end what NATO now understands to be a long conflict, and Putin views as a ‘forever war’.

The starting point for a better European approach is rooted in empathy within the Western alliance for diverging views. Based on acknowledging that we might see things differently for very legitimate reasons, we can begin to build strong coalitions around clear and realistic war aims. Rather than falling back on opposite historical reflexes, Europe should collectively put its mind to ending the present war in Ukraine both in the present and in Ukraine.

- Sebastian Schutte is a Senior Researcher at PRIO