Both the two-state and one-state solutions exist only in the imagination. Time has run away from them, as things stand today.

Jerusalem, December 2023. Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The violent conflict between Israel and the Palestinians has been going on for 75 years, with Israel emerging stronger from all of the more serious outbreaks of warfare. How can this conflict be resolved?

A biblical answer from a rabbi was apparently that ‘it can happen by natural means – that would be a miracle. Or it can happen because of a miracle – that would be the natural course of events’.

The Israeli ‘trilemma’

At the heart of the conflict is the parties’ irreconcilable territorial claims. Although Israel has emerged stronger, the country has a fundamental problem. It cannot be a Jewish state, a full democracy and an occupying power all at the same time. This problem has been referred to as the Israeli ‘trilemma’.

Two of these elements can be combined, but not all three. For Israel to be both Jewish and democratic, it must withdraw from the occupied West Bank, where it is oppressing almost three million Palestinians. This is known as the two-state solution.

The establishment of a democratic and multinational country encompassing Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, with equal rights for all, would cause Israel to cease to be a Jewish state. This is known as the one-state solution. A Jewish state that annexes ever larger portions of the West Bank without giving Palestinians the right to vote can no longer be characterized as democratic. This is known as the ‘Greater Israel’ solution.

These are the three incompatible solutions that are being debated today.

The two-state solution

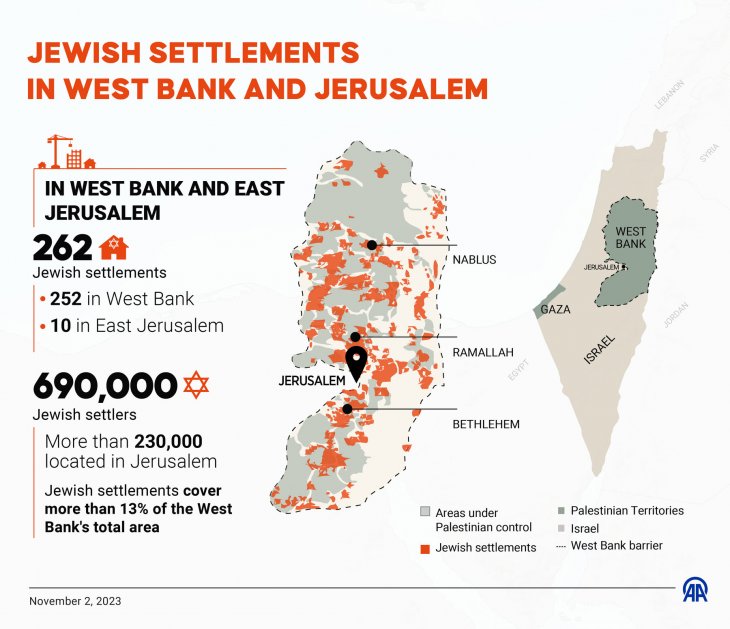

The main barrier to the two-state solution is Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem and the ever-increasing number of Israeli settlers in the West Bank. When the United States launched its so-called ‘Roadmap for Peace’ in 2002, there were around 380,000 settlers in the West Bank. The Roadmap was based on reciprocal recognition, an end to violence, a ban on new settlements, and the dismantling of settlements that Israel had not authorized.

Mahmut Resul Karaca / Anadolu via Getty Images

Israel found that it was impossible to freeze the growth of the settlements. The Palestinians wanted East Jerusalem to be handed back and for the Jewish settlements to be dismantled. In addition, there was a rise in political rivalry and the split between Hamas and Fatah/the PLO. The Roadmap fizzled out.

Today there are twice as many Israeli settlers – more than 700,000 – in the West Bank as there were in 2002. The Israeli government subsidizes them with cheap housing, and they provide Israel with a buffer against militant Palestinians. Many of the settlers are religiously motivated, identifying the West Bank with the biblical regions of Judea and Samaria. Many are heavily armed and can almost be characterized as paramilitaries.

Israel was able to force a modest number of Israeli settlers out of Sinai following its peace agreement with Egypt in 1978. It was also able to force several tens of thousands of settlers out of Gaza before it blockaded the area in 2005. But how would it succeed in forcing 700,000 armed settlers out of the West Bank?

Currently the Israeli government is permitting an increase in the number of settlements in the West Bank. Many people see this increase as a step towards full annexation. Even unauthorized settlements enjoy military protection and other benefits.

Even if an Israeli government wished to force the settlers out, doing so would be almost impossible. Any such attempt would split Israel into violent factions. Demographic changes in Israel, with the arrival of more orthodox and extremist groups, makes the two-state solution far more difficult than it was in 2002.

Ten years ago, around half of Israelis could envisage a Palestinian state in the West Bank. Today this number has sunk to barely a third, if we are to believe opinion polls conducted before the Hamas attacks on 7 October. Support for a two-state solution is in continual decline.

The one-state solution

The one-state solution, whereby Israel, the West Bank and Gaza would become a multinational state, has very little support among Israeli Jews. Such a solution would undo the basic reason for founding the state of Israel in 1948 – to establish a national homeland for Jews from all over the world. A further barrier to this solution is that such a state would soon have a majority Palestinian population. A one-state solution would be opposed with armed force by powerful factions, who would have the support of the majority of Israel’s Jewish population.

Both the two-state and one-state solutions exist only in the imagination. Time has run away from them, as things stand today.

The ‘Greater Israel’ solution

The third solution is Israel’s annexation of ever larger parts of the West Bank. This is what is happening on the ground, with support from the Israeli government and from a growing proportion of Israel’s population. One problem is that this solution has minimal international support, because it breaches international law and involves the oppression of around five million Palestinians on the West Bank and the Band of Gaza’. Another problem is that this solution would cause even more members of the Palestinian population to become radicalized and engage in constant attacks from within.

The so-called Allon Plan of 1967, named after Israel’s then defence minister Yigal Allon, proposed that Israel and Jordan should divide up the West Bank between themselves, with Jordan taking greater responsibility for the Palestinian population. This plan has guided the policy of some Israeli governments in relation to the settlements. It was a step towards the Greater Israel envisaged by some radical Jewish groups.

Ever since 1948, there have been extremist Jewish groups who have believed that the Palestinians already got their separate state with the founding of Jordan in 1946. But the Palestinians in the West Bank are not welcome in Jordan.

When the PLO and a large number of Palestinians relocated to Jordan after the Six-Day War in 1967, tensions within Jordan increased dramatically.

Jordan declared war on this Palestinian presence in September 1970. The conflict is still remembered as Black September. No country in the Middle East wants to increase the number of Palestinians within its borders.

A miracle

There are no signs of any easy solutions in the Middle East. The routine references to a two-state or a one-state solution are political rhetoric, without any basis in reality.

A long-term solution will depend on a combination of new terms and bold decisions that are not apparent to us today. In biblical language, this is known as a miracle. In modern everyday language, we tend instead to talk about unforeseen events with momentous consequences.

Such events do happen, as with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the ending of the apartheid regime in South Africa in 1993. In the meantime, perhaps a lid can be kept on the level of conflict, as the Cold War kept a lid on the conflict between the Soviet Union and the West in the years prior to 1989.

- Øyvind Østerud is Professor of Political Science at the University of Oslo. He was chair of the PRIO board 2003-2006.

- This text was first published in Norwegian in Aftenposten 4 December 2023.

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext