Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February, food insecurity and food prices have become increasingly concerning. However, the focus has largely been on the consequences of war for the international market and food insecurity abroad, leaving less attention to the lack of food among civilians in Ukraine.

Supermarket in Svetlodarsk, Ukraine. Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid

Ukrainians have fled their homes, lost their jobs and income, and faced disruptions of food production and supply chains. In a recent survey in Ukraine, we asked a series of questions to explore food insecurity in more detail. The findings paint a grave picture: one in three Ukrainians are currently food insecure. The findings also indicate that those living in the east, those who are more exposed to attacks, and — not surprisingly — those who are the least well off in the first place are the most endangered by food insecurity.

What do we know about war and food insecurity?

Food insecurity can be caused by many factors, including climate variability and extremes, economic downturns, and — especially — war. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), around half of people who are undernourished and 80 percent of stunted children reside in countries experiencing armed conflict or widespread violence. However, existing knowledge is largely based on studies of poor rural areas in Asia and Africa, and the focus is typically on the long-term effects of conflicts on food insecurity, through pathways such as child stunting, malnutrition, or disruption of agricultural production. In these settings, households are already exposed to factors associated with food insecurity, such as droughts and low economic development, and so wars become additional shocks to already vulnerable situations. By contrast, we know much less about the immediate impacts of armed conflicts, particularly in contexts outside the Global South, and not least in urban settings.

What is the current status of food security in Ukraine?

In an original survey conducted in April 2022, we asked some 800 Ukrainians whether they were experiencing food insecurity. Specifically, we asked the respondents to consider the last seven days and report on how many days they: 1) did not have enough food to eat, 2) had to limit the portion of meals, and 3) did not have enough potable liquids to drink.

As many as 36 percent reported not having enough food to eat; 52 percent were limiting the portions of meals; and 29 percent did not have enough liquids to drink for at least one day. Given that our survey agency could not reach all respondents in areas of intense fighting, these percentages are likely underestimates.

Possible reasons for people lacking food are the disruption of food supply in stores in areas under attack and lower food production within Ukraine, as well as people not being able or willing to risk going outside to secure a meal during fighting.

Who are the most vulnerable?

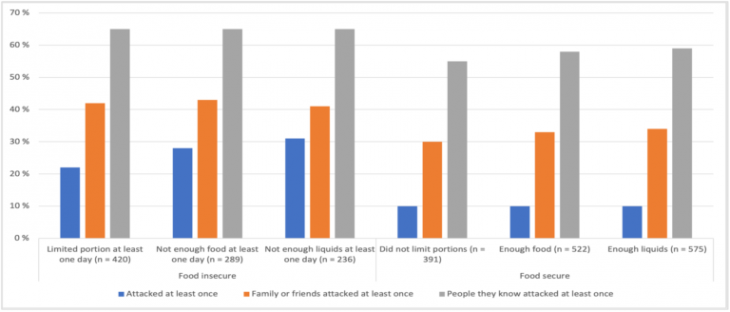

Those who reported food insecurity were also more likely to report having experienced one or more attacks, either personally or among family, friends, or acquaintances. For respondents who indicated limiting their meals, 22 percent reported that they had been directly attacked by Russian forces (in a two-week period before the interview), 42 percent reported that their family or friends had been attacked, and 65 percent reported that people they know had been attacked. The corresponding figures for those not limiting their meals were lower: 10 percent, 30 percent, and 55 percent, respectively. The percentages were similar for other indicators of food insecurity (see Figure 1).

Our research also suggests considerable regional variation in food insecurity across Ukraine. In early April, Ukrainians regained control of large areas around Kyiv after the Russian forces shifted focus from the capital to the east and south of the country. Reflecting this, more than half (57 percent) of people residing in eastern Ukraine reported not having enough food for at least one day. In the south, approximately 42 percent reported the same. In the western, central, and northern regions, the analogous percentages were lower: 27 percent, 31 percent, and 31 percent respectively. In Kyiv, the percentage was 44 percent.

Moreover, those who reported having the least money, education, and employment were also those most likely to report food insecurity. Specifically, among the 20 percent of Ukrainians who placed themselves at the bottom of a socioeconomic ladder, 69 percent reported having to limit their meals, whereas the corresponding figure for those in the next rung up the economic ladder was 47 percent.

What can be done?

Altogether, our data suggests that the war in Ukraine influences the level of reported food insecurity among Ukrainians, with more intense attacks associated with higher levels of food insecurity. To mitigate the adverse effects of war, the international community must strive to ensure sufficient and safe access to affordable food for civilians in Ukraine, both by keeping supply chains open and enabling farmers to maintain their livelihoods. In the short term, this entails maintaining global trade and setting up alternative trade routes, avoiding export bans, and encouraging food subsidies to the most vulnerable. In the long term, agricultural production and distribution must return to prewar levels to ameliorate food insecurity both within Ukraine and beyond, particularly in African and Middle Eastern countries that are dependent on food imports to meet domestic consumption levels.

Ida Rudolfsen is a senior researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Gudrun Østby is research director and research professor at PRIO. Henrikas Bartusevičius a senior researcher at PRIO. Florian van Leeuwen is assistant professor at Tilburg University.

ABOUT THE SURVEY

The data on war exposure and food insecurity were collected as part of a larger project that interviewed Ukrainians over two survey waves. The first survey wave was conducted between 9 and 12 March 2022 and the second between 3 and 11 April 2022. Both waves were administered online in Ukrainian and Russian by the local survey agency Info Sapiens. The survey recruited respondents between 18 and 55 years old in areas with over 50,000 inhabitants and aimed to generate a representative sample of the Ukrainian population. However, some of the Ukrainians who were beyond Ukraine’s borders, or in areas of intense military combat, were not reached by the survey agency. A total of 1,081 people were interviewed in the first survey wave, and 811 were reinterviewed in the second wave.

This blog post is based on the second survey wave. The statistics presented above were generated using sampling weights to represent population patterns.

The analysis and opinions in this summary and the blog should only be attributed to the authors.

The first survey wave was supported by the Alexander-von-Humboldt prize to Mark van Vugt, and the second wave was supported by the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). The following scholars were involved in designing the first wave: Henrikas Bartusevičius (PRIO), Lasse Lausten (Aarhus University), Honorata Mazepus (Leiden University), Florian van Leeuwen (Tilburg University), and Mark van Vugt (Vrije Universiteit Anmsterdam). The second wave was designed by the same five scholars, plus the following scholars from PRIO: Pavel Baev, Helga Malmin Binningsbø, Marta Bivand Erdal, Haakon Gjerløw, Nic Marsh, Louise Olsson, Gudrun Østby, Ida Rudolfsen, Siri Aas Rustad, Andreas Forø Tollefsen, Henrik Urdal, Torunn L. Tryggestad.

- This post was first published by Political Violence @ a Glance 7 July 2022.