The lessons an ancient Greek war can teach Ukraine today.

Ukraine is confronted with a stark choice: fight on through a bitter winter with death raining from above, or initiate negotiations with Russia under unfavorable terms. Two-and-a-half millennia ago, the leaders of the Greek island of Melos confronted a similar choice.

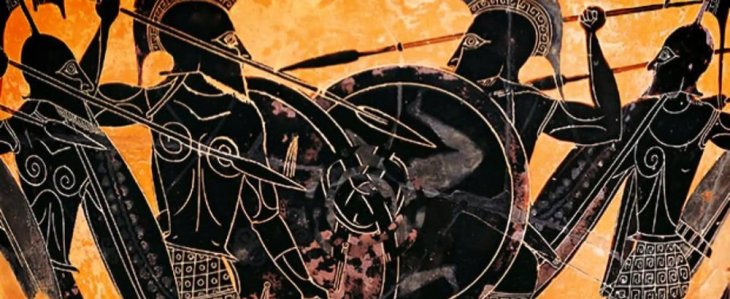

The leaders of Melos were faced with the prospect of either submitting to Athenian rule or risking annihilation. This was the proposition conveyed by the Athenian envoys, as recounted by Thucydides in his classic study of the Peloponnesian War. The Melians unequivocally had justice on their side. But Thucydides was at pains to show that justice alone is never enough. Unless right is allied with might, confidence in the truth of one’s cause can become a fatal trap — a siren song that too easily condemns the just to doom.

Hoping in Sparta — their motherland — the Melians refused any compromise with Athens that might weaken their independence. An early battlefield success bought the Melians some time, but their Spartan friends failed to arrive. Athens renewed its attack with a much larger force, and the island was roundly defeated. Its men were put to death, its women and children enslaved. Athens colonized the island with its own settlers.

The historical record of Thucydides’s morality tale is mixed.

Against reasonable odds, Britain prevailed against Nazi Germany in the air war of 1940, a feat doubly remarkable because British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had no ally to lean on in this hour of need. He refused to negotiate, and history applauded his choice.

French Marshal Philippe Pétain, by contrast, signed a peace deal. The French could have continued the struggle with their naval fleet and might have waged guerilla warfare, but their leader opted for safety, to his longstanding disgrace. A cloud of shame still hangs over the French nation today, albeit partially lifted by the heroic resistance movement and the military action led by General Charles de Gaulle.

During the same period, Finland offered a different lesson. In 1939, it fought heroically against Soviet aggression, with Western backing. After significant battlefield losses, it signed a peace agreement with the Soviet Union in March 1940, wherein it consented to the loss of substantial territory.

Finland broke the agreement a year later and sought to retake its lost territory in coordination with Germany’s Operation Barbarossa. Initially successful, Finland then suffered a severe Soviet backlash, leading it to sign a new peace agreement in 1944. Finland lost the same territory as in 1940 (Karelia), and now also Petsamo in the north. It subsequently helped the Soviets by chasing the German army out of northern Finland into Norway. Nonetheless, to this day, Finland has not recovered its lost territory, nor does it persist in demanding it back. Instead, Finland has asked for NATO membership.

What can Thucydides’s tale teach us about Ukraine today? The analogy may help us see a prospect of recurring war interspersed with agreements between Ukraine and a resurgent Russia in years ahead.

But it could also tell us the story of a Ukraine that may, as Finland has done since 1945, accept the loss of some territory, retain its independence, and thrive economically in an integrated Europe.

Morality makes a political difference today in a way that it did not for Thucydides. We have international law and clearly stated rules of war. To compromise in a way that in essence hands the aggressor a victory because of its immoral and illegal actions can invite further transgressions. Yet a refusal to compromise can likewise be disastrous, and for that reason, immoral.

The Melian leaders were valiant, but their naivete had tragic consequences for their people. Present-day Melians, on the other hand, would have a negotiating power and allied support that the poor island inhabitants and their diplomats did not. That could be an argument in favor of negotiating.

As Ukraine faces a winter of devastation and widespread suffering brought on by Russian aggression, how will it be possible to avoid a Melian tragedy? The negotiating table, with all its deficiencies, represents a possible way ahead, not as an alternative to continued fighting in the cause of freedom, but as a necessary complement to it.

President Volodymyr Zelensky could press for full justice, which in this case would entail a Russian withdrawal from all occupied areas, including Crimea. But to achieve this result Ukraine would need to secure a decisive battlefield victory over Russia — an unlikely scenario in the near term. Short of such victory, to end the war Ukraine must be prepared to accept something less than full justice.

Henry Kissinger has recently proposed that Ukraine should be willing to cede its claim over Crimea to secure peace within its prewar borders (the status quo ante). We are reluctant to make a concrete recommendation such as this. In our view, it is up to Ukraine to decide where its national interest lies.

What history can teach us — and this we think is Thucydides’s message for us today — is that compromise can be a wise course of action. A desire to see full justice prevail should not blind us to this important truth.

In the event negotiations take place, a party respected by both sides — India, for instance — would be a suitable mediator. The negotiations should begin with a temporary ceasefire and a deadline for reaching agreement. Crimea would most likely be on the table, while Russian withdrawal from eastern Ukraine to internationally recognized borders would be a reasonable baseline demand.

Beyond that, we should hope for fair negotiations conducted in a manner consistent with widely agreed tenets of international law and morality. That is certainly preferable to the amoral pressure that the Athenians so brutally put on the Melians, and to which the Melians reacted so valiantly, and yet so self-destructively.

- The authors are Research Professors at PRIO

- This text was first published by Commonweal Magazine 22 December 2022

Comparing the Western backing Finland received in 1939 with Ukraine today is farfetched, to put it mildly.

Comparing the aid given by the West to Ukraine today to the aid given Finland during the 1939-40 Winter War in our view makes sense. In both cases, there was massive sympathy for a country invaded by Russia. Non-lethal aid was provided by private citizens as well as states to the valiant defenders of national sovereignty. Voluntaries from many countries joined Finland’s fight, including some Ukrainians. Yet the lethal, logistical and financial aid given Ukraine today of course far exceeds what Finland could get from countries engaged in The phoney war, waiting for Germany’s next move.

This gives us an occasion to correct a mistake we made in our op ed. We wrote that Finland had to cede the same territories in August 1944 as in 1940 (Karelia) but forgot to mention that in 1944, Finland also had to give up Petsamo in the north, which by then had been occupied by the Soviet Army.

Stein Tønnesson