A sinister mixture of geopolitical changes, nationalist sentiments, and election campaigns now has the potential to generate one of the world’s most dangerous security crises.

On 14 February, a terrorist attack in Pulwama in the Indian state Jammu & Kashmir killed more than 40 Indian Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) paramilitary troopers. This was the deadliest terror attack witnessed in decades of the insurgency in Kashmir and was carried out by the Pakistani based group Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM).

A furious India promised revenge, while Pakistan denied involvement. India immediately took steps to isolate its neighbour politically and economically and Indian PM Narendra Modi made clear that there would be a military response. On 26 February, Indian aircraft bombed targets behind the Line of Control (LoC) that separates the two nuclear powers in the disputed region of Kashmir. The two countries disagree about the effects of the airstrikes and the conflict took a new turn when it appeared that Indian Wing Commander Abhinandan Vartaman had been shot down and taken into custody by Pakistan. The pilot was soon returned in what PM Imran Khan called a peace gesture.

What is the larger historical and geopolitical context of this latest flare in the conflict between India and Pakistan?

What is the larger historical and geopolitical context of this latest flare in the conflict between India and Pakistan? South Asia is home to almost two billion people, or a quarter of the world’s population. The region can be analyzed as an international political system that consists of the countries India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Nepal and Bhutan. In addition, China, Iran, Russia and the United States are involved as third parties to varying degrees. But the international system that comprises South Asia is in a state of change.

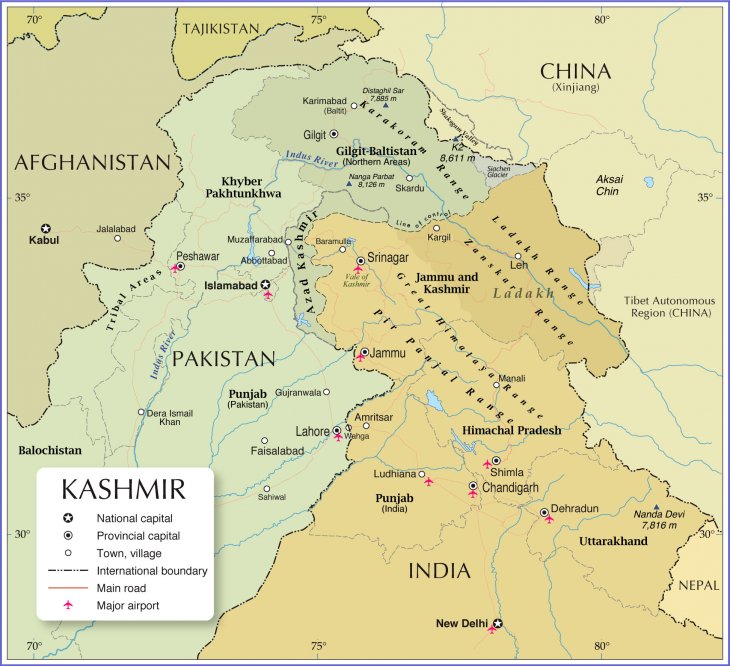

Kashmir / Nations Online

Your enemies’ enemies

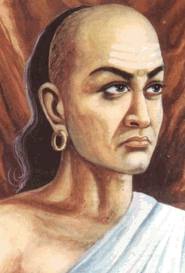

In the second century BCE, the legendary Indian author Kautilya wrote a treatise called the Arthashastra, known in English as the Science of Politics. The text was subject to a number of changes over the next centuries and its analyses of political and social life have shaped Indian political culture through the ages. In my opinion, the Arthashastra is the most fascinating work in all of classical Indian literature. A key idea in the treatise is the circle of states.

In the second century BCE, the legendary Indian author Kautilya wrote a treatise called the Arthashastra, known in English as the Science of Politics. The text was subject to a number of changes over the next centuries and its analyses of political and social life have shaped Indian political culture through the ages. In my opinion, the Arthashastra is the most fascinating work in all of classical Indian literature. A key idea in the treatise is the circle of states.

According to Kautilya, a national leader should see himself as surrounded by a circle of enemies. This means that the next circle of states is formed of natural allies, and foreign policy is about how best to weaken one’s enemies by collaborating with their enemies.

Kautilya seems to have had something of a renaissance in modern Indian strategic thinking. A couple of years ago, Delhi’s leading defence policy think-tank, the Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (IDSA), published a three-volume work on Kautilya’s ideas and concepts. The stated aim was to “study, internalize, disseminate and consolidate” Kautilya’s thinking about strategy.

Could undermine peace in Afghanistan

From Delhi’s point of view, changes are now occurring in the circle of states. During the Cold War, Pakistan was of key importance because the United States needed the country as an ally in its proxy war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. After the end of the Cold War, Pakistan could have lost this status, but then came 9/11.

When the United States went to war in Afghanistan to neutralize the threat from Al-Qaeda, Pakistan regained its strategic importance, and from Washington’s perspective it was crucial to ensure that India and Pakistan remained at peace.

But with the United States now withdrawing from Afghanistan, the war-ridden country could quickly become the battleground for an intensified conflict between India and Pakistan.

India has devoted considerable efforts to gaining influence and soft power in Afghanistan. The two countries signed a strategic partnership in 2011 and India has since provided military training, donated equipment, constructed infrastructure, provided student scholarships and built a library, which was recently mocked by Trump.

For Pakistan, however, a close friendship between India and Afghanistan is a threat. Competition between third-party powers for influence could undermine peace in Afghanistan, a country that has always been a crossroads and a battleground for Eurasian civilizations, a tragic situation poetically captured in the concept of the Great Game, the 19th century contest between Russia and Britain.

The fear of China

During his 2016 election campaign, Trump flirted in a rather comic fashion with America’s India diaspora with his barely recognizable Hindi slogan “Ab ki baar, Trump Sarkaar” (This time, Trump government) adapted from PM Modi’s Indian election campaign of 2014. Trump pointed out that India was very important to the United States, which has been the stance taken by American presidents since Clinton.

The United States has needed Pakistan in Afghanistan, but at the same time Washington has understood that India is in many ways of much greater importance.

India is the natural enemy of China, and accordingly could provide the United States with a counterweight against China’s power in Asia.

In a speech right after 9/11, A.B. Vajpayee (the then Indian PM) said that the United States and India were “natural allies”. Vajpayee was a far more sophisticated thinker than India’s current PM, Narendra Modi, and had certainly read Kautilya’s Arthashastra.

From Beijing’s perspective, by contrast, Pakistan is China’s “natural ally” in South Asia.

China wants to dominate its part of the globe and is attempting to surround India through a combination of new alliances and economic collaboration with countries such as Pakistan and Sri Lanka. This is the perspective from Delhi, at any rate, and at times this outlook is generating panic in India’s foreign policy circles. Seen from a distance, China seems far too occupied with its own internal problems and with the new Great Game in the Pacific to really be a threat to India.

India wants influence

In the midst of all these changes, India, the world’s largest democracy, is holding parliamentary elections in a few weeks. The last elections, in 2014, were an enormous success for the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and provided a strong mandate for Narendra Modi’s government.

A populist and charismatic leader, Modi has been accused of being responsible for large-scale atrocities during his political career as chief minister of Gujarat. Modi’s and BJP’s Hindu chauvinism is certainly a problem for minorities in India, but this is not particularly significant for understanding South Asia as an international political system. In the governing party’s 2014 election manifesto, Modi claimed that he would “fundamentally reboot and reorient the foreign policy goals, content and process”.

Several analysts have claimed that Modi’s foreign policy is a fundamental reorientation, perhaps even a break with the past or a paradigm shift. To support such a position one could point to the fact that foreign policy is to a large degree shaped by the PM and there is little doubt that Modi has put a personal stamp on India’s foreign relations, for instance in his active engagement with immediate neighbours to forge a more friendly international environment in South Asia.

Modi’s extremely personal style is fundamentally different from that of the previous prime minister, Manmohan Singh, an uncharismatic bureaucrat, but much of the essence of India’s foreign policy remains unchanged. India wants influence and recognition as a major power regardless of which party occupies the PM’s office. India wants global recognition, but is continually drawn into local quarrels with Pakistan, its little sibling. India and Pakistan are states that were carved out from British India at the stroke of a pen in 1947 in history’s largest experiment in the politics of religion.

War and caution

Terrorism can play a part in these geopolitical changes, unfortunately. Modi has much to lose because opinion polls have shown that he could lose his grip on power in the upcoming elections.

Indians are dissatisfied with his policies, but he could perhaps regain some popularity with the correct response to a terror attack.

Pakistan’s relatively fresh prime minister, Imran Khan, also has much to prove. He has been criticized for neither understanding nor liking military might, but as PM he cannot be a pacifist: he must defend Pakistan’s borders and national honour.

So where are we heading? Immediately after the attacks on 14 February opinions were divided among colleagues and friends in India who are familiar with the country’s security policy.

Some were certain that the countries simply cannot go too far but have learnt to handle a permanent state of crisis. And the present tensions are not nearly as serious as the Kargil crisis in 1999.

Others think that the threat of war is perhaps more serious than ever not least because of the upcoming elections and the desire to show assertiveness.

Ultimately India would win either a limited conventional war or, God forbid, a nuclear confrontation. But victory would be hollow when one imagines the human cost.

And so let us hope that Modi too has read Kautilya’s Arthashastra. Classical Indian political thinking is both cynical and pragmatic, and counsels against the use of war as a means in international relations. “Only a person who lacks a knowledge of weapons can be heroic,” is a recurrent theme in this literature.

The problem is that populist leaders of democracies cannot afford too much realism. A sinister mixture of geopolitical changes, nationalist sentiments, and election campaigns now has the potential to generate the world’s most dangerous security crisis.

- This text was first published in Norwegian in Aftenposten 27 February 2019: Kan det bli krig i Sør-Asia?

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext

Excellent analysis-a blend of historical and contemporary perspectives.

Operating intensively and intentionally can be tedious and painful experience for us.