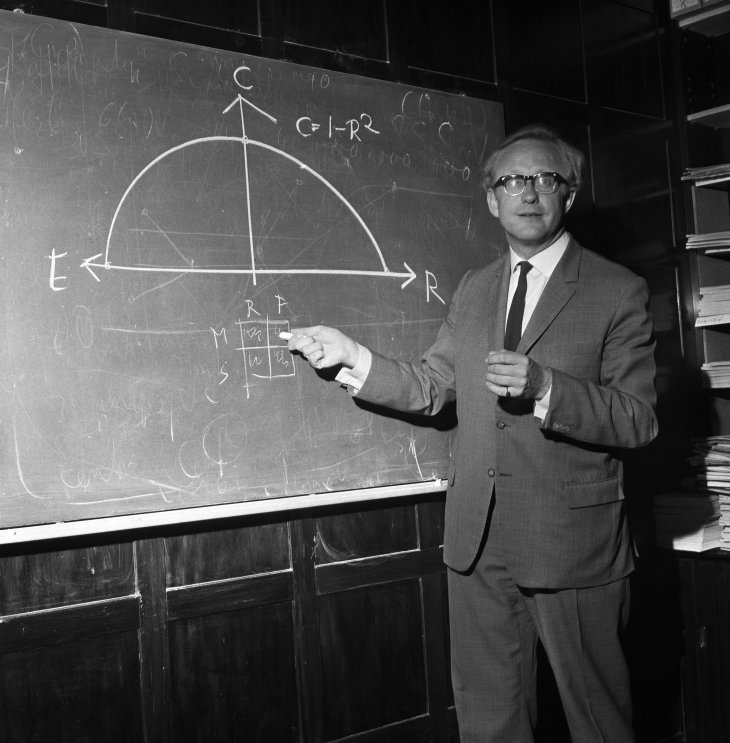

Johan Galtung lecturing in 1968. Photo: Henrik Laurvik / NTB / Scanpix

The banner on the front page of PRIO’s Annual Reports and other publications proudly reads:

Independent • International • Interdisciplinary

These three key points for PRIO today, as well as other important features of contemporary peace research in Oslo, can be traced back to PRIO’s founder, Johan Galtung. He turns 90 today.

Independent

While PRIO started out in 1959 as the Section for Conflict and Peace Research of the Institute for Social Research, the goal was clearly an independent institute. Greater autonomy was reached in 1964 when Norwegian government funding was provided through the new Council for Conflict and Peace Research. This was signaled through the section’s new name, Peace Research Institute Oslo, which remains the name today. Full independence with a separate Board was achieved (amicably) two years later. But the independence went well beyond the secession. When Johan Galtung was hired by the University of Oslo to a new Chair in Conflict and Peace Research in 1969, PRIO was not incorporated into the University. A final measure of independence is that the core funding has always come through the Ministry of Education and Research and from the Research Council and not from the Foreign Ministry. This independence is alive and well today. Even if the Norwegian Foreign Ministry has become a significant source of project funding, its importance is dwarfed by funding from the Research Council of Norway and similar sources.

International

The choice of name was no coincidence. ‘Oslo’ was part of the English name, but only to indicate the location – a model copied later in Copenhagen, Stockholm, Tampere, and elsewhere. In Norwegian, the institute’s name is simply Institutt for fredsforskning (‘Institute for Peace Research’). There are numerous institutes labeled ‘Norwegian Institute for …’. PRIO is not one of them. Although the core staff has been mainly Norwegian, guest researchers from other countries have played an important part in PRIO’s life from the start, including students recruited by Galtung through his extensive international network. To achieve an international impact, the two academic journals founded by Johan Galtung, Journal of Peace Research (1964) and Bulletin of Peace Proposals (1969, now Security Dialogue) are published in English. With a discreet nod to the dominant international conflict at the time, the first ten volumes of JPR even carried a kratkoye soderzhanie (later rezhume) – a translation into Russian of the articles’ abstracts.

The perspective on conflict was truly international rather than ‘we’ versus ‘them’. The themes were of general relevance. There were some case studies and articles with mainly Norwegian empirics, but they were framed in a way to gain knowledge of wider relevance. One of Galtung’s early and most frequently cited articles, with a theory of foreign news, had data from Norwegian newspapers about four international conflicts – but that is definitely not why it has become such an important text in media studies. PRIO’s staff today is even more international and includes several tenured non-Norwegian members. The research portfolio reflects the same international orientation.

Interdisciplinary

While the three members of PRIO’s core staff in 1959 were sociologists, Galtung’s first graduate degree was in mathematics and he recruited adjunct staff members from history, social anthropology, psychology, and law and eventually a large number of graduate students from across the social sciences. The first Editorial Board for JPR listed 32 members from nine disciplines. A similar diversity is very much reflected in PRIO’s staff today, as illustrated by the work of philosophers in the study of civil war, the use of economic models in the study of conflict, the cooperation of anthropologists, geographers, and sociologists in designing fieldwork, and the widespread adoption of geographic information systems in the work of political scientists. It might be more accurate to use the term cross-disciplinary (or multi-disciplinary) than interdisciplinary for some of this work, and Galtung’s ambition for transdisciplinary research is more rarely achieved.

The nonviolent tradition

But there are additional continuities. Galtung’s first academic work in peace research was a study with Arne Næss in 1955 that attempted to synthesize Gandhi’s political ethics. Nonviolence had a prominent place on PRIO’s early agenda. When I was hired as a research assistant in 1964, my first project was on nonviolent resistance as a means of national defense. Since then, the study of nonviolence has wandered in and out of PRIO’s active research portfolio. Today, it occupies an important place in the study of means and agents of conflict and political change.

Johan Galtung, 1965. Photo: PRIO archives

Publish or perish!

Galtung’s most widely cited work (see addendum, below) is found in articles, notably from Journal of Peace Research in the period 1964–71. He co-authored with contemporaries and students and encouraged (even pressured) his colleagues to get their work published, as those of us who grew up under his mentorship well remember. A classic reflection of this is found in the acknowledgements section in a 1966 article in JPR by Nils Halle: ‘The author wishes to express his gratitude to Johan Galtung for constructive criticism and ingenuity in making the writing an experience of horror, thus enhancing the relief when the paper was delivered …’.

But his pressure for publication was also a mark of confidence in his colleagues and students. Peter Wallensteen and Raimo Väyrynen, who went on to become professors in Sweden and Finland respectively and gain a high international standing, had no reason to regret that JPR published their articles when they were just 23 years old. Such a feat is more difficult to achieve in the age of rigorous peer review and publication lags. But the high frequency of article-based dissertations at PRIO is an illustration of an environment that encourages early publication, as is the continuing co-authoring by mentor and student. PRIO’s overall publication profile shows that a pattern of active journal publication persists in the later career of PRIOites.

Policy implications

The first editorial in JPR in 1964 (unsigned but written by Galtung) stressed that peace research should not be limited to an evaluation of existing policies; ‘it should also be peace search, an audacious application of science in order to generate visions of new worlds’. For years, JPR authors were encouraged to round off their work with a section on policy implications. Even today, ‘Without sacrificing the requirements for theoretical rigor and methodological sophistication, articles directed towards ways and means of peace will be favored.’ The combination of first-rate academic articles with the PRIO Blog and other means of research communication to a general audience represents a continuing effort to live up to the institute’s ambition to achieve what is now called ‘engaged excellence’.

PRIO as a community

One of the intriguing aspects of being introduced to PRIO in its founding years was to experience a research community that went well beyond a work fellowship and the publication of written products. Research thrived in an atmosphere of friendship and cooperation. This tradition has survived, although the community-building now relies more on the work of dedicated staff members than on the heroic efforts of the founder’s then wife.

Methods

Finally, and perhaps most controversially, methods. Given that Galtung was trained as a mathematician and sociologist, it is not surprising that PRIO and JPR formed part of the behavioral revolution in the social sciences. Galtung’s 1967 methods textbook remains his most influential book. The starting-point for peace research in the first JPR editorial, ‘under what conditions are people in general willing to …’, is a question calling for nomothetic research, aiming at finding general relationships, although Galtung also specified the need to ‘use the tools that suit the problem’. The four articles by Galtung that make it to the top ten of JPR’s most-frequently-cited articles all provide precise definitions suitable for operationalization and building testable hypotheses, although only two of them engage in empirical testing. His two JPR articles on structural violence and cultural violence are probably chiefly remembered today for their conceptual innovation and ideological overtones, but they were also attempts to put problems raised in the political debate on a more rigorous footing for systematic research.

Although Galtung moved on from the behavioralism of his youth (as early as 1974 he called for ‘invariance-breaking’ as an alternative to establishing regularities, his positivist legacy lives on, as his citations statistics demonstrate clearly.

PRIO’s present project portfolio is methodologically quite diverse and the staff’s work in new areas like studies of critical security, gender, and migration has gained wide academic recognition. But the institute’s international standing is still to a large extent tied to quantitative data projects, models of civil war, and systematic studies of liberal and realist conceptions of peace. The Centre for the Study of Civil War, PRIO’s Centre of Excellence (2003–12) and the first such center to be established in the social sciences in Norway, had a clear nomothetic agenda, as does the first PRIO project to be hosted by the Centre for Advanced Studies at the Norwegian Academy of Science.

Galtung’s legacy

The continuity from the founder to today’s PRIO, even after 60 years, may seem trivial. But the founder himself has moved on in so many ways. This is not surprising. Kenneth Boulding’s assessment in 1977 is still apt: ‘There are some people like Picasso whose output is so large and so varied that it is hard to believe that it comes from only one person. Johan Galtung falls into this category.’ In his interview for the 60th anniversary series, PRIO Stories, the founder tends to see peace research in Oslo as too conventional, strongly tied to Norwegian government policy, and largely monopolized by political science. JPR has become ‘an American journal’. (As the journal’s former editor for nearly three decades, I strongly dispute this statement, but that is beside the point.)

While Galtung still has a wide and possibly even growing circle of supporters, in Norway as well as internationally, his links to PRIO have progressively weakened over the years. This is reflected in a modest poll that I conducted among the present staff regarding how Galtung’s work had influenced their own. This survey and its results are available at the link provided in the box below. Very few of today’s staff consider Galtung as an important influence in their own academic work, while over 60% respond ‘not at all’ or ‘not very important’. The same percentage applies to staff from the Conditions of Violence and Peace program, the most positivist of PRIO’s departments. At times, PRIOites have gone on record distancing themselves from some of Galtung’s more controversial polemics in the public debate, while at the same recognizing his pioneering contribution. Today’s Director of PRIO, Henrik Urdal, says in the Norwegian transcript of his anniversary interview with Galtung that ‘we do not know each other’.

But despite the apparent divergence, Johan Galtung continues to exercise considerable indirect influence on how peace research is conducted in Oslo. I rest my case and extend my congratulations to PRIO’s founder for a long, varied, and controversial research career.

*

Nils Petter Gleditsch was one of the graduate students recruited to PRIO in the early 1960s under Johan Galtung’s mentorship. He went on to become Head of PRIO (1972, 1978–79) and to serve as Editor of Journal of Peace Research (1976–77, 1983–2010). He wishes to acknowledge valuable comments on an earlier draft of this text from PRIO colleagues as well as from Raimo Väyrynen and Peter Wallensteen, while absolving everyone of any responsibility for the final product.

It’s amazing that someone in 2020 can produce this much text about Johan Galtung without even mentioning his promotion of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and other (even worse) antisemitic literature. Or his support for the trope that Jews somehow “declared war” on Germany, an old trick used by Hitler supporters to portray Nazi persecutions as some sort of defensive measure.

Or Galtung’s use of a pamphlet by legendary neo-Nazi William Pierce to discuss Jewish control of the media (when asked by Norwegian state broadcaster NRK about this, Galtung replied that he had no reason to doubt the factual content of the text). Or that his webpage Transcend Media Service now publishes outright Holocaust denial.

This is why organisations that have previously lauded Galtung, such as the Norwegian Green Party and the Norwegian Humanist Union (the latter is my employer) have today distanced themselves from him.

I understand that his admirers (albeit a rapidly shrinking group in recent years) want to laud Galtung for his positive contributions, but this text is pure revisionism.

This text is from 2012. Galtung has just become more adamant in his spread of antisemitism since then.

https://www.nrk.no/norge/_-en-trist-sorti-for-galtung-1.8098250

It’s amazing that someone in 2020 can produce this much text about Johan Galtung without even mentioning his promotion of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and other (even worse) anti-Semitic literature. Or his support for the trope that Jews somehow “declared war” on Germany, an old trick used by Hitler supporters to portray Nazi persecutions as some sort of defensive measure.

Or Galtung’s use of a pamphlet by legendary neo-Nazi William Pierce to discuss Jewish control of the media (when asked by Norwegian state broadcaster NRK about this, Galtung replied that he had no reason to doubt the factual content of the text). Or that his webpage Transcend Media Service now publishes outright Holocaust denial.

This is why organisations that have previously lauded Galtung, such as the Norwegian Green Party and the Norwegian Humanist Union (the latter is my employer) have today distanced themselves from him.

I understand that his admirers (a rapidly shrinking group in recent years) want to laud Galtung for his positive contributions, but this text is pure revisionism.

This article is from 2012. If anything, Galtung has become more adamant in his use of antisemitic talking point since then.

https://www.nrk.no/norge/_-en-trist-sorti-for-galtung-1.8098250

There are links to the debate about the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the penultimate paragraph of my blog post. Beyond that, let me just say that my post is not a biography of Johan Galtung, but had a specific theme: what parts of Galtung legacy can be recognized today at the institution he founded 61 years ago.

I understand the purpose of the article. But when you then choose to mention Galtung’s “controversial polemics”, while linking to a piece where Galtung dismisses all criticism, you’ve strayed from that and taken his side.

PS to moderators: Sorry for posting the same comment twice, I thought something had gone wrong and reposted. Feel free to delete one of them.

There are two links at that point, one where Galtung is severely criticized and one where he tries to explain what he meant. I leave it to the readers to judge for themselves.

Yes, there are two links. The first is a link to Galtung’s attempt at an explanation and the second to a “page not found” on PRIO’s webpages.

Not sure how this helps the readers decide for themselves.

I’m truly sorry about that. The link was correct in my ms, but something must have gone wrong when it was posted on the blog. In any case, the link now works.