In recent years, nationalist leaders have staked claims on lost territories in order to restore the glory of former empires. Lars-Erik Cederman believes that this rise in revanchist nationalism poses a threat to geopolitical stability.

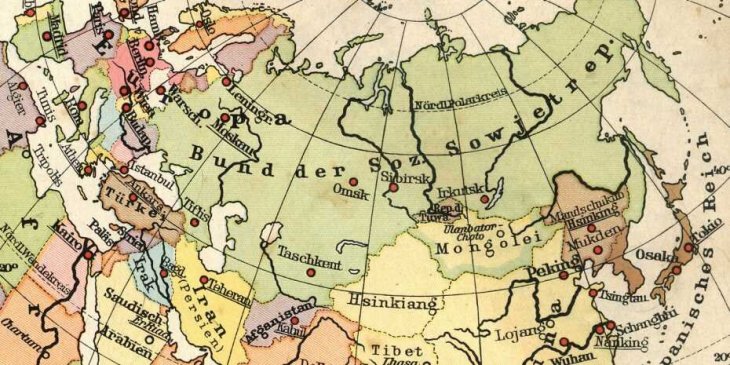

The Soviet Union — a “golden age” from the perspective of neo-imperialists (historical map). Credit: iStock / troyek

Imperialism is thought to be a thing of the past. Yet in recent years, populist nationalists have increasingly expressed a strong sense of longing for their states’ imperial past. Russian President Vladimir Putin views the collapse of the Soviet Union as one of the greatest disasters of the 20th century and has begun reclaiming lost territory by annexing Crimea in 2014.

Similarly, in his nostalgia for a grander, imperial Ottoman past, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has revealed an interest in irredentist expansion that includes North Cyprus and Syrian border regions. As a reflection of a deep identity crisis following the loss of the British Empire, the Brexit process may ultimately rekindle the conflict in Northern Ireland and break up the United Kingdom.

The empire is dead – long live the empire!

Formal empires may be dead, but in the playbook of aggrieved nationalists who want to make their countries “great again”, the temptations of revisionism loom large. As vividly demonstrated by Putin’s Crimean land grab, the norms of peaceful border change have come under pressure in recent years. Leading states have shown little regard for international law, as reflected in the Trump Administration’s recognition of Israel’s occupied territories. While Trump’s electoral loss gives the liberal world order some respite, there is no doubt in my mind that it has been severely weakened.

To a large degree, the aforementioned tensions are the result of ethnic nationalism, an ideology that holds that political borders must coincide with national ones. Nationalist tensions frequently emerge in cases where multiple ethnic nations inhabit the same state or where members of the same nation remain divided by current borders.

Yearning for a past golden age

Together with my team, I have produced an analysis showing that the geopolitical fragmentation of ethnic groups is an important driver of civil conflict. Moreover, we emphasize that ethnic nationalists do not merely react to current injustices, but also often refer to a past “golden age” in their rhetoric.

In Putin’s case, the reference point is the USSR, and in case of Erdogan, the Ottoman Empire. Thus, what counts is not just a lack of unity, but a loss of unity compared to a real or mythical point in history that can date back very far. Using geocoded data on state boundaries and ethnic groups since the late 19th century, we can show that violent rebellions against established states are more likely when ethnic groups are fragmented by current borders and when the fragmentation increases.

In the ongoing ERC project on Nationalist State Transformation and Conflict (NASTAC), my team and I are currently extending this research by going even further back in time to study the historical roots of modern states and ethnic nationalism.

Wars of territorial expansion

So far, we have been able to confirm the great sociologist Charles Tilly’s thesis that warfare drove state formation and territorial expansion of great powers in early modern Europe. We have also shown that the rise of ethnic nationalism has reversed this previous trend toward larger states. In fact, since the early 20th century, states have been shrinking steadily, especially due to the collapse of multi-ethnic empires.

Thus, our research confirms that nationalism continues to threaten geopolitical stability. I believe that the coming years will reveal whether the forces of liberal democracy and power sharing regain their momentum or whether we are entering a much darker era characterized by ethno-nationalist domination and violent conflict.

Much will hinge on developments in the West: in particular the power struggles inside the US and the EU, where currently democracy, the rule of law, and multi-ethnic tolerance are challenged by vocal illiberal forces. Ultimately, belief in the liberal world order rests on a successful track record of delivering wealth and security to the masses. In my view, failure in these crucial respects will create even more demand for populist nationalism and neo-imperialist adventures.

- Lars-Erik Cederman is a Professor of International Conflict Research at ETH Zürich, and a long-standing PRIO associate. Seraina Rüegger and Guy Schvitz contributed to this blog post. Alongside Lars-Erik Cederman, both are also co-authors of the forthcoming article “Redemption through Rebellion: Border Change, Lost Unity and Nationalist Conflict”, which will soon be published in the American Journal of Political Science.

- This text was first posted at ETH Zürich´s Zukunftsblog 6 January 2021.

References

- Cederman LE: “Blood for Soil: The Fatal Temptations of Ethnic Politics”; Foreign Affairs 98: 61, 2019

- Cederman LE: “Nationalism and Ethnicity”. In The Handbook of International Relations, eds. Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse and Beth Simmons, Sage, 2013