Threat identification and threat inflation are clearly important elements in international affairs. However, determining which threats and fears people and policymakers will embrace as notable and important is difficult. Thus, the American public and its leaders have remained remarkably calm about the dangers of genetically modified food while becoming very wary of nuclear power. The French see it very differently. In the United States, illegal immigration from Mexico is seen to be a threat in some years, but not in others. The country was “held hostage” when Americans were kidnapped in Iran in 1979 or in Lebanon in the 1980s but not when this repeatedly happened during the Iraq War or in Colombia. Milošević in Serbia became a monster worthy of attention and alarm, but not Mugabe in Zimbabwe or SLORC in Burma or Pol Pot in Cambodia or, until 9/11, the Taliban in Afghanistan.

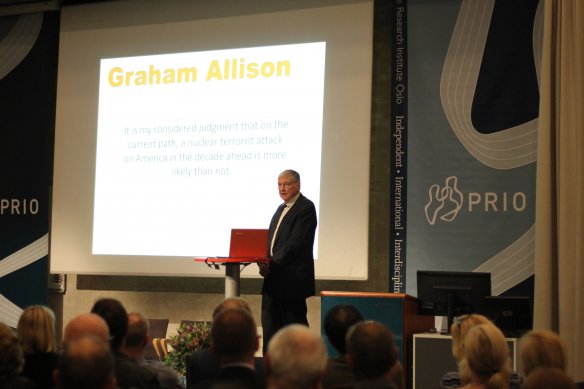

John Mueller at the PRIO Annual Peace Address.

However, it does seem that every foreign policy threat in the last several decades that has come to be accepted as significant has, in the process, been unwisely exaggerated. As a result, over the last several decades, alarmism has been prominent in thinking about international security. When successfully generated, alarmism very frequently leads to two responses that are serially connected and often prove to be unwise, even dangerous. First, a threatening event is treated not as an aberration, but rather as a harbinger indicating that things have suddenly become much more dangerous, will remain so, and will become worse—an exercise that might be called “massive extrapolation.” And second, there is a tendency to lash out at the threat and to overspend to deal with it without much thought about alternative policies including ones that might advocate simply letting it be. There is, as Noël Coward once put it in different context, a “dread of repose.” I would like to examine alarmism during the Cold War about the nature of the Soviet threat and alarmism after 9/11 about the threat presented terrorism. I conclude with a discussion about the relevance of deterrence to the process.

With this I do not wish to suggest that all fears are unjustified or that international threats are never underestimated. In fact, I suspect that some of the tendency to inflate threats in the period after World War II derives from the fact that the threat presented by Adolf Hitler’s Germany had been underappreciated in the period before it (and Hitler was keen to help: in virtually all of his foreign policy speeches of the 1930s, he spoke of his ardent desire for peace). The post-war proclivity toward exaggeration and overreaction may also stem in part from the traumatic prewar experience with Japan when there had been something of a tendency to underestimate its capacity and, in particular, its willingness to take risks. Robert Jervis has suggested that “those who remember the past are condemned to making the opposite mistakes.” The pre-war experience with Hitler and with Japan may have been too well remembered.

Read More